For years, Ukrainian experts have warned that the Moscow Patriarchate’s church network often serves not just religious purposes but strategic ones. This suspicion – long evident in Ukraine – is now gaining traction across Europe, from Sweden and Norway to the Netherlands. In the wake of Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many European governments expelled dozens of Russian diplomats accused of spying, only to find that Moscow was shifting to alternative covers for its operatives. One such cover, investigators now suggest, is the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) itself, whose parishes abroad may double as an intelligence network.

An open-source investigation by the Molfar Intelligence Institute in late 2024 concluded that the ROC “continues to construct churches near strategic facilities, government institutions, and military bases across various European countries” – a systematic effort to use religious outposts for espionage. European security services are starting to heed the warnings: from Scandinavia to the heart of Europe, Orthodox churches aligned with Moscow are under intense scrutiny for their proximity to sensitive sites and ties to the Kremlin’s security apparatus.

Sweden: The Church by the Airport Raises Alarm

On the outskirts of the city of Västerås, about 100 km west of Stockholm, a newly built Russian Orthodox church has become the focus of national security concerns. The Russian Orthodox Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in Västerås, Sweden, was constructed between 2013 and 2019. Locals noted its high fence and CCTV cameras, unusual for a small parish. The church was consecrated in November 2023 and sits at a remarkably strategic location – just 500 meters from Västerås Airport, a standby airfield for crisis use, 4.2 km from a Westinghouse nuclear fuel factory, 6 km from a major power plant, and under 5 km from an ABB metallurgy complex. Such a concentration of critical infrastructure around the church immediately raised eyebrows. It later emerged that Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation, had quietly purchased the land in 2013 and financed the church’s construction. Local journalists were struck by the unusually swift permitting process for the project, as well as the presence of an opaque perimeter fence and surveillance cameras around the chapel. At the consecration ceremony, one guest in particular stood out: Vladimir Lyapin, a senior diplomat from the Russian Embassy, who is one of 20 Russian envoys in Scandinavia suspected by authorities of being intelligence officers.

The priest in charge at Västerås, Father Pavel Makarenko, has vehemently denied any impropriety – even as Swedish media revealed he once received a commendation from Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). Makarenko had previously run a Swedish-registered company linked to a Russian developer implicated in drug trafficking, and that company, with no warehouses to speak of, somehow boasted tens of millions of kronor in revenue. Notably, Makarenko’s ecclesiastical career in Sweden shows a pattern of assignments uncannily near military sites. Before Västerås, he led parishes in Arboga and Gävle – towns where the Russian churches happen to sit just a few kilometres from Swedish Armed Forces facilities. Such coincidences have not been lost on Swedish investigators.

Swedish authorities are now taking action. In mid-2024, the Swedish Security Service (Säpo) informed the government that the Russian state “uses the Russian Orthodox Church in Sweden as a platform to conduct intelligence activities in Sweden”. Following Säpo’s warning, the state agency that disburses grants to religious organisations promptly cut off funding to the ROC in Sweden. “These are serious times, and it is necessary for us to pay attention to what is going on around us,” said Staffan Jansson, a local council leader, after Säpo’s disclosure. In short, what looked at first like an innocuous place of worship now appears to Swedish eyes as a potential outpost of Moscow’s spy network.

Sweden’s Västerås church may be the most high-profile case, but it is hardly the only suspicious ROC site in the country. Investigations have identified a pattern of Russian Orthodox chapels placed near strategic assets in Sweden, including:

- Arboga: A small ROC parish established just 8.4 km from a key Swedish Armed Forces communications and IT installation.

- Gävle: A parish located 1.9 km from a National Guard battalion headquarters and about 1.1 km from a military training ground, with a railway line only 140 m away.

- Uppsala: An ROC church merely 750 m from a government facility and 2.7 km from an air force base and academy. Its abbot, Father Vitalii Babushin, was abruptly sent from Moscow to Sweden in 2010 and now also works for the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department of Foreign Institutions in Jönköping.

- Stockholm: The St. Sergius parish in the capital sits 4 km from the Swedish Defence Ministry and 6 km from the Armed Forces headquarters. Even more strikingly, its affiliated Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh is in a district clustered with foreign embassies – seven embassies (including those of Czechia, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania and others) lie within a one-kilometre radius. The abbot, Father Nikita (Oleh Dobronravov), is an official of the ROC’s External Church Relations department in Moscow, underscoring the direct line between these parishes and the Moscow centre.

- Gothenburg: The ROC parish of the Protection of the Holy Mother of God in Sweden’s second-largest city is about 2 km from a major power plant and 12 km from a military installation. Its overseer, Archpriest Sergey Bondarev, also happens to run another parish in the port city of Helsingborg – that church is a mere 1.4 km from a commercial port facility.

- Boliden: In this remote northern town, a ROC church of St. Nicholas was built in 2017 just 500 m from the entrance of a mining company extracting strategic minerals – zinc, copper, gold and more. Local Swedish media have openly speculated that this church’s real mission is espionage. The parish’s deacon, Aleksandr Bednov, is a retired Soviet military pilot and trained lawyer – an unusual résumé for a village clergyman – fueling suspicions that Boliden’s “priesthood” might be less innocent than it looks.

In all these cases across Sweden, the modus operandi appears consistent: modest Russian Orthodox establishments popping up near militarily or economically sensitive sites, often backed by opaque funding and staffed by figures with links to the Russian state. As one Swedish defence researcher observed, such churches offer “a potential foothold” for Russian intelligence – a literal lookout point to monitor nearby airports or industries, and a cover for agents to mingle on the ground. The pattern in Sweden has effectively blown the whistle for the rest of Europe.

Norway: Parishes in Strategic Shadows

Norway has likewise discovered that several ROC entities on its soil sit uncomfortably close to strategic locations. The Norwegian Police Security Service (PST) has not publicly detailed cases as bluntly as Säpo did, but independent analyses show a striking geography of Orthodox churches and chapels in Norway aligned with Moscow’s patriarchate, placed near military, industrial, or government sites. Notable examples include:

- Oslo: The parish of Saint Princess Olga, operating since 2003 in the capital, lies in the central district just a few hundred meters from key government facilities. Within a 1 km radius of the church are Norway’s Parliament (Stortinget), the Statistics Bureau (SSB), multiple ministries, and at least seven foreign embassies. This parish is led by Archimandrite Fr. Kliment (Juha) Khukhtamyaki – a Finnish-born cleric personally tonsured by Patriarch Kirill in 1996 and dispatched to Norway to establish Moscow-aligned parishes. Even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Khukhtamyaki refused to break with the ROC or condemn the war. His longstanding ties to Kirill and his role in expanding the ROC network in Norway have not gone unnoticed.

- Bryne: In this small industrial town in southern Norway, the Church of the Holy Martyr Irene was built in 2014 amid a cluster of high-tech manufacturing firms. Within an 800 m radius of the church are companies specialising in advanced metalwork, robotics automation, and semiconductor components – including Nordic Steel AS (650 m away) and IXYS Norway, about 586 m away. Such firms supply Norway’s energy and engineering sectors, and their proximity to a Russian parish established post-2014 raises red flags. The parish rector, Archpriest Vasily Petrov, simultaneously holds a position at a Russian seminary and in March 2022 signed an infamous open letter by ROC clergy justifying Russia’s actions in Ukraine – a stark indication of his loyalties.

- Kirkenes: At Norway’s northeastern frontier with Russia, the ROC’s parish of St. Tryphon of Pechenga has operated since 2015 in the border town of Kirkenes. This area is of acute strategic interest: the church is just 5 km from the Sør-Varanger Garrison (which guards the NATO-Russia border) and sits within a few hundred meters of the local municipality offices and the Russian Consulate-General. Kirkenes has long had close people-to-people ties with Russia, and journalists report that the Moscow Patriarchate quietly acquired property there in 2015 to cement its presence. Even two decades ago, Vladimir Putin personally showed interest in establishing a “maritime” Russian church in Kirkenes during a state visit, though that early plan never materialised. The current parish’s location — amid a nexus of military, civic, and Russian diplomatic sites — revives concerns about what purposes it may truly serve.

- Vardø: On a remote Arctic island in Vardø, not far from Norway’s sensitive GLOBUS radar installation, a Russian Orthodox chapel was under construction from 2017 until recently. Vardø’s radar, operated by Norwegian intelligence with U.S. support, is widely believed to also feed into NATO’s missile defence system – making it one of Norway’s most guarded assets. Incredibly, the ROC managed to secure local approvals and even Norwegian state grant money, channelled via a cross-border “friendship” program, to build a chapel here. An FSB-linked veterans’ organisation from Murmansk was involved in exchanges related to the project. The notion of a Russian chapel overlooking a NATO radar sparked alarm, and ultimately, the construction plans were cancelled amid heightened scrutiny after 2022. The Vardø episode stands as a stark example of how far Moscow is willing to push the envelope – and how local goodwill initiatives were cynically used to mask strategic designs.

- Trondheim: Even Norway’s historic city of Trondheim has an ROC footprint near military sites. The Parish of St. Anna of Novgorod, built in 2008, lies within 1.3 km of several defence facilities, including a submarine bunker, an air force academy, and army installations, as well as near the city’s naval port. A host of NATO countries ‘ consulates (those of Finland, Poland, Denmark, the Netherlands, etc.) are also within a kilometre of this church. Such a location could offer an observant “parishioner” ample opportunity to note military movements. In 2017, a Russian Bishop from Moscow’s Department for Institutions Abroad paid a high-profile visit to Trondheim’s ROC congregation – a signal of the parish’s importance. Local analysts can’t help but wonder if this small church’s mission was about saving souls or monitoring submarines.

Across Norway, the pattern echoes Sweden’s experience: churches are placed where spies might wish to lurk. It is telling that Russian religious figures in Norway, like Fr. Khukhtamyaki and others, have direct lines to Patriarch Kirill and have largely toed Moscow’s political line. What might once have been dismissed as a conspiracy theory – that a church could be a cog in an espionage machine – now prompts sober analysis. Norwegian media and experts increasingly connect the dots between Moscow’s “Orthodox missionaries” and the Kremlin’s intelligence goals.

Finland: Shuttering the “Parish” of Spies

Finland, which shares a long border with Russia, acted early when suspicions about Russian Orthodox activities arose. In August 2022, authorities in the city of Turku shut down the local Russian Orthodox parish – the Church of the Dormition of the Holy Mother of God – citing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as the impetus. This was a remarkable step: effectively evicting a Moscow-linked church amid concerns it could threaten national security. The Turku parish’s location was certainly conspicuous. It sat near the Pansio naval base, home to Finland’s coastal fleet, not far from the Port of Turku, and in proximity to the city hall and the Regional State Administrative headquarters – and almost next door to Russia’s own Consulate-General. In other words, a Russian religious outpost positioned within the same neighbourhood as a Finnish naval facility and Russia’s diplomatic mission. With war raging in Ukraine, the optics were untenable. Turku’s city government, unprecedentedly, decided to close the church – a bold precedent that signalled Finland’s resolve to scrutinise Moscow’s religious diplomacy.

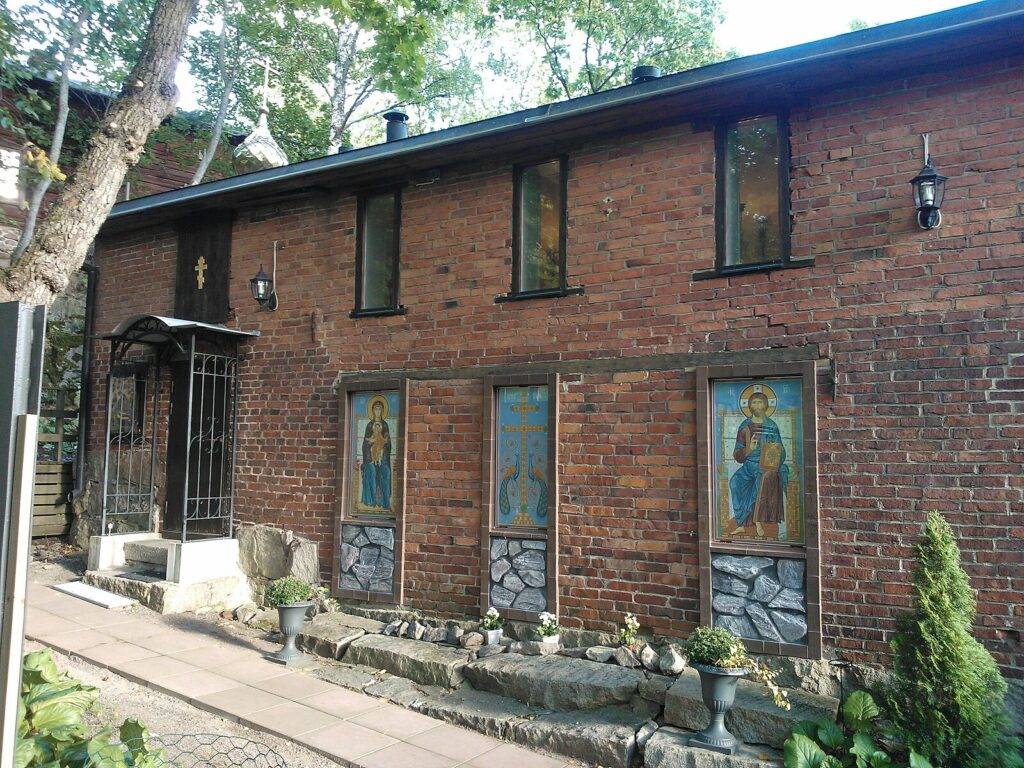

Elsewhere in Finland, Russian Orthodox sites have also drawn attention. In the capital Helsinki, the Parish of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, active since 1938, is located within a 3 km radius of at least half a dozen military or maritime installations and several government offices. Helsinki’s role as Finland’s political and naval hub means any out-of-place presence is noticed. It has not escaped observers that the ROC’s Helsinki parish maintains close ties to the Moscow Patriarchate; its clergy, like others in Europe, have avoided criticising the Kremlin’s war. Additionally, a smaller ROC chapel built in 2000 in eastern Helsinki sits near the Vuosaari commercial port and a major power plant – again, locations of interest beyond the spiritual realm. Finnish security services have reportedly kept these sites on their radar. And in a broader sense, Finland’s recent accession to NATO and historic shift away from neutrality have only heightened concerns about Russian espionage on Finnish soil. The closure of the Turku church in 2022 signalled that Finland will not hesitate to curtail Moscow’s religious footprint if it appears to undermine national security.

Netherlands: Churches Near Government and Defence Hubs

Even in Western Europe’s heartland, the pattern persists. The Netherlands – far from Russia’s borders, but host to key international institutions – has uncovered suspicious circumstances around a few Russian Orthodox establishments. One prominent case was The Hague, home to numerous international courts and agencies. There, the ROC opened a male monastery in 1972 (the Monastery of John the Baptist, under the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad), which operated quietly for decades. After Russia’s invasion, however, Dutch authorities and journalists began noting that the monastery’s location was in a dense cluster of government and defence-related facilities. No fewer than 29 government offices were in its vicinity, including the headquarters of the Federation of European Defence Technology Associations (only ~400 m away) and a Dutch Army facility (~2 km away). The outer harbour and a major power plant were also within a few kilometres. In an atmosphere of growing mistrust, the Hague monastery closed down in December 2022, shortly after the war began. While the official reasons given were routine or financial, the timing and context suggest it had become untenable for a Russian-affiliated institution to operate at such a sensitive location. Dutch commentators have openly questioned whether that monastery had a dual mission beyond prayer, considering the valuable intelligence that could be observed or gathered from its perch.

In the port city of Rotterdam, another case stands out. The Russian Orthodox Church of St. Alexander Nevsky was built in 2004 with the involvement of a Russian construction firm and was personally consecrated by Patriarch Kirill, then Metropolitan. Its current rector, Father Anatoly Babiuk, has notably declined to comment on Russia’s war against Ukraine, raising suspicions about his allegiances. The Rotterdam church sits in the midst of critical infrastructure. Around nine government buildings, including the Rotterdam Prosecutor’s Office (just over 1 km away), are nearby. According to investigative reports, within a 3–4 km radius of the church are also two military facilities, a maritime logistics hub, and a supplier of power-plant equipment. Such proximity again seems unlikely to be pure coincidence. Additionally, Rotterdam hosts an older ROC parish (established in 1959, dedicated to an icon of the Theotokos), which likewise is situated near important infrastructure. The Netherlands has a long tradition of tolerance, but security experts have started to voice concern that Russian churches could be exploited as cover for surveillance – especially in a country that hosts the International Criminal Court and other entities of keen interest to Moscow’s spies. Dutch intelligence agencies, in step with their European partners, have been tightening their watch on any unusual activities linked to these parishes. As one OSINT summary noted, the close proximity of Russian religious sites to government institutions in the Netherlands “raises concerns and questions about their potential use in a broader geopolitical context”.

Czech Republic: Influence Operations Under the Cross

In Czechia, revelations about the Russian Orthodox Church have fuelled a political pushback. Though Czech Orthodoxy is traditionally under the jurisdiction of a local church, Moscow’s influence has seeped in via personnel and financing. Notably, in Prague, the historic Cathedral of Saints Cyril and Methodius, which belongs to the Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church) received substantial funding for restorations from Gazprom Neft, the Russian state oil company. The Archbishop of Prague even awarded a medal to a Gazprom Neft advisor in thanks for his assistance to the cathedral. This overt financial tie to the Kremlin’s energy arm set off alarm bells. Lawmakers in Prague began asking why a Russian state company was so interested in a Czech church, and what influence that might buy. Their concern is part of a broader trend: Czech authorities have been “tightening the screws” on Russian-linked entities since it emerged that Russian GRU agents blew up ammunition depots on Czech soil in 2014. In that light, even ostensibly benign church activities are getting new scrutiny.

Some Czech officials are openly sceptical that Moscow-affiliated clergy in their country are there purely for pastoral work. “I do not consider the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate to be a church and its representatives to be clergymen,” Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský said in August 2024. “It is part of the Kremlin’s repressive machine that is involved in Russia’s influence operations”. This blunt assessment came as Czech authorities sanctioned Patriarch Kirill himself and expelled at least one Russian Orthodox cleric from the country. Parliamentarians have also called for investigations into whether ROC outposts in Czechia are conducting “influence operations” under religious cover. Their suspicions are not unfounded. In Moravia, for instance, the Orthodox Cathedral of Gorazd in Olomouc lies about 70 km from the site of the 2014 Vrbětice munitions depot explosions – a sabotage orchestrated by Russian agents. While that distance is considerable, the coincidence underlines how ROC sites have cropped up even in regions later touched by Russian covert aggression. And in the rural village of Vrbětice itself, a small Orthodox chapel, the Chapel of the Life-Giving Trinity, exists about 72 km from the former depot, serving as a reminder of the Russian religious presence in the area. Czech investigators are examining whether these and other Moscow-linked religious facilities could have facilitated Russian spying or subversion activities before or after that notorious attack. At the very least, Prague’s security establishment now regards the ROC as a potential fifth column. What was once viewed simply as a cultural or spiritual outpost of the Russian diaspora is increasingly seen as an “active tool of Russian government soft power,” in the words of one analyst.

The Pattern is No Accident

The emerging picture across Europe is difficult to ignore. In country after country, Russian Orthodox churches and monasteries – especially those under the direct jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate – appear frequently sited near strategically significant locations. This pattern is no accident, investigators suggest, but a deliberate strategy by Moscow. “It has never been a secret that Russia uses the church and Orthodox values as a significant part of its foreign policy,” noted Vladimir Liparteliani, a scholar at Durham University, in a Radio Free Europe interview. Indeed, the Kremlin has intertwined religion with statecraft, and Patriarch Kirill has been one of Putin’s staunchest allies, blessing the war in Ukraine as a holy mission. European states are belatedly waking up to the implications. As Liparteliani explained, when countries move to constrain the ROC’s activities, “it is essentially trying to reduce the impact of Russian soft power”. And that soft power, cloaked in the cassock of faith, can be wielded for hard espionage purposes.

Other cases beyond the aforementioned countries reinforce the point. In Bulgaria, for example, authorities expelled three ROC priests (two Belarusian, one Russian) in 2022 on national security grounds – a dramatic step that underscored suspicions of espionage under religious cover. In Estonia, the government recently declined to renew the residence permit of the head of the local Moscow-affiliated Orthodox Church, citing him as a security risk due to his overt justification of Russia’s war and likely ties to Moscow’s services. And at the pan-European level, institutions have started to respond: in October 2024, the Council of Europe went so far as to label the Russian Orthodox Church a tool of Kremlin influence, part of a resolution that also sanctioned Russian propagandists. The message is clear – Europe’s tolerance for Moscow’s religious diplomacy is wearing thin.

To be sure, not every Russian Orthodox congregation abroad is a spy nest, and many ordinary worshippers are doubtless genuine in their faith. But the institutional ROC – especially where it falls under Moscow’s hierarchy – has shown itself to be tightly interwoven with the Russian state. Ukrainian security services, fighting an existential war, learned this the hard way: they have arrested priests for treason, raided ROC monasteries used as intelligence hubs, and ultimately banned the Moscow-led church on Ukrainian territory. Now, Europe at large is catching on. As an investigation by Molfar concluded, the ROC’s expansion near sensitive sites “appears to be part of a well-thought-out system,” allowing Russia to use a religious front for espionage activities, gathering valuable intelligence that could even be shared with allied rogue states like Iran or North Korea. This poses “a serious threat to European security” if left unchecked.

Mitigating that threat will require vigilance and coordinated action. Western security agencies are beginning to monitor these Orthodox parishes with the same scepticism as they would a suspect foreign cultural centre or business. Some countries have started to tighten laws on foreign religious groups, increase surveillance on ROC clergy travels, or freeze projects for new Russian churches near strategic locations. The challenge, however, is steep: Moscow will undoubtedly protest such measures as “Russophobia” or repression of religious freedom. Navigating the line between protecting liberal societies and closing down a hostile spy network masquerading as a church will test Europe’s resolve and legal frameworks.

What is beyond doubt is that European nations can no longer afford to view all churches as purely benign sanctuaries. In an era of hybrid warfare, a gilded Orthodox dome on the skyline might not only symbolise faith – it may double as an antenna for foreign intelligence. As one security expert put it, “While Kirill attempts to justify imperial aggression, Ukrainians and their allies must remain alert. Russia can hide hostile eyes and ears under a religious façade, and that reality should shake off any naiveté”. The West has learned that spies may pray, and priests may spy. Facing that fact is now part of defending Europe’s security in the age of Russian hybrid war.

Read More:

- Molfar Intelligence Institute: Is the Russian Orthodox Church Spying in Europe? Molfar Research. Part One

- Radio Free Europe: Pro-War Policies Put Russia’s Orthodox Church Under Increasing Pressure Outside Russia

- France24: Investigating Russian Orthodox Church in Sweden

- Politico: New Russian church raises suspicions in Swedish town

- The Moscow Times: Sweden Cuts Support for Russian Church After Intelligence Warnings

- Hackyourmom: Russian Orthodox Church Espionage in Europe: Religion or Intelligence?

- Hackyourmom: Church in Sweden

- Euronews: (Un)orthodox intelligence operations: How Russia is using its churches abroad

- NOEK: Sweden cuts funding to Russian Orthodox Church after it’s deemed a security threat

- United24: Russia’s Spy Network Under Moscow’s Religious Cloak

- United24: Holy Cover? Sweden Probes Russian Orthodox Church Over Espionage Suspicions

- United24: Sweden Raises Security Concerns over Russian Orthodox Church Near Strategic Airport

- Dagens: New Russian Church in Sweden Could be Spying on Strategic Facilities

- The Insider: Swedish authorities suspect new Russian Orthodox church of espionage near airport and other strategic locations

- Norran: After Säpo’s warning: Russian church dodges questions

- FOI: Russia’s use of religion for military purposes

- Orthodox Christianity: Swedish politicians hope to expropriate Russian church near airport over “security concerns”

- BelSat: An Orthodox church near Stockholm, under FSB patronage, could pose a significant threat to Sweden and NATO’s security

- Norran: Russia’s Trojan horse in Sweden: The Orthodox Church