In the midst of Cold War détente, an unlikely diplomatic milestone took shape in Helsinki, Finland. From 30 July to 1 August 1975, 35 nations – every European country, except Albania, plus the United States and Canada – convened for the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). The most dramatic manifestation of the Helsinki Accords’ unintended power came in Poland in 1980, with the Solidarity Movement.

The meeting, initiated by the Soviet Union’s longstanding proposal for a pan-European security conference, aimed to solidify East–West relations. Western leaders had been sceptical for decades, fearing that confirming the post-World War II status quo would “strengthen the Soviet position” in Eastern Europe. However, by the early 1970s, the atmosphere of détente made such talks possible, and after two years of negotiations the parties gathered in Helsinki to sign a historic accord. The Helsinki Final Act, also known as the Helsinki Accords, was signed on 1 August 1975 in Finlandia Hall. At the time, many observers underestimated its significance. The agreement was not a formal treaty and carried no legal enforcement mechanism. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger privately dismissed the process as something “we never wanted… [it] is meaningless”, reflecting a common belief that the conference would merely ratify Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.

Indeed, the Soviets themselves saw Helsinki as a triumph: they gained explicit Western acceptance of European borders as they stood – essentially legitimizing Moscow’s postwar control over the Baltic states and its satellite bloc. At the time, few could imagine that this seemingly innocuous diplomatic meeting was a turning point. As Kissinger later admitted, “turning points often pass unrecognized by contemporaries”. In hindsight, the 1975 Helsinki Conference planted the seeds of a revolution that would blossom in the 1980s, undermining communist regimes from within and ultimately contributing to the Soviet empire’s collapse.

The Helsinki Final Act: Human Rights amidst Cold War Realpolitik

The Helsinki Final Act itself was a comprehensive document addressing security, cooperation, and human rights. It was divided into “baskets” covering different areas of East–West relations. In Basket I, the participating states agreed to ten guiding principles. the “Helsinki Decalogue”, for international conduct. These principles included both the Soviet Union’s priorities – such as respect for sovereignty and non-interference – and Western insistence on human rights. The ten points were:

- Sovereign equality and respect for inherent rights – affirming each nation’s sovereignty and independence.

- Refraining from the threat or use of force – renouncing force to resolve disputes.

- Inviolability of frontiers – accepting Europe’s existing national borders.

- Territorial integrity of States – pledging not to violate other states’ territory.

- Peaceful settlement of disputes – committing to resolve conflicts diplomatically.

- Non-intervention in internal affairs – agreeing not to interfere in other states’ domestic matters.

- Respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms – including freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and belief.

- Equal rights and self-determination of peoples – affirming all peoples’ right to determine their political status “in full freedom…without external interference”.

- Co-operation among States – to promote mutual understanding and economic, scientific, and cultural collaboration.

- Fulfillment in good faith of international obligations – honouring international law and agreements.

These principles struck a careful balance. The Eastern Bloc was pleased to see principles affirming sovereignty, territorial integrity and non-interference, which they interpreted as tacit acceptance of their rule in Eastern Europe. Western democracies, however, placed great value on Principle VII – human rights and fundamental freedoms, and Principle VIII on self-determination. By signing the Final Act, the Soviet Union and its allies publicly committed to respecting citizens’ basic rights and the freedom of peoples to choose their destiny. “The participating States will respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, for all without distinction,” the text declared. They further pledged to “promote… the effective exercise of civil, political, economic, social, cultural and other rights and freedoms” . These words, however non-binding, would not remain empty.

Another section of the accords (Basket III) expanded on human contacts: it called for freer movement of people and ideas across borders, family reunifications, improved conditions for journalists, and cultural exchanges. Such clauses were anathema to hardline communist regimes, which feared foreign ideas sparking unrest. A secret Hungarian government memo at the time warned that Western “imperialists intend to capitalize on the contents of the Final Act” by exploiting the free flow of information to undermine communist authority. In short, even as they signed the document, Eastern bloc leaders were deeply wary of its potential to erode their control. Their cynicism was not misplaced.

It’s important to note that the Helsinki Final Act was explicitly not a legally binding treaty – it relied on the good faith of governments to implement its provisions. There were no enforcement mechanisms or sanctions for violations. At first glance, this seemed to favour the Kremlin: Moscow gained the de jure recognition of post-war borders it craved, while conceding only vague humanitarian principles that it assumed it would safely ignore. But in the court of world opinion – and in the hearts of their own peoples – those humanitarian promises carried moral weight. Western leaders understood this. As one U.S. diplomat presciently argued in 1975, even if the Final Act only partly succeeded, “the lot of the people in Eastern Europe will be that much better, and the cause of freedom will advance”. In other words, if the Soviet bloc kept its word on human rights, Eastern Europeans would gain new breathing room; if it broke its word, the breach would be obvious to all.

Dissidents Seize the “Helsinki Spirit”

Almost immediately after 1975, the Helsinki Accords became a reference point and rallying tool for dissidents behind the Iron Curtain. The conference gave birth to what came to be called the “Spirit of Helsinki” – the notion that even bitter adversaries could engage in dialogue and agree on universal principles, including human rights. Eastern Europeans heard their governments endorse these principles in Helsinki, and they planned to hold them to their word. As the Atlantic Council later noted, “the phrase ‘Helsinki process’ became synonymous with human rights activism and monitoring in the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc”, overturning initial expectations that the Final Act would only cement the status quo.

By 1976, activists in Moscow formed the Moscow Helsinki Group to monitor the USSR’s compliance with the Accords. Similar citizen “Helsinki committees” soon sprang up elsewhere in the Eastern bloc. These groups bravely documented human rights abuses and demanded that their governments live up to the promises made in Helsinki. In Czechoslovakia, for example, 243 intellectuals and activists published Charter 77 in January 1977, directly invoking the human rights clauses of the Helsinki Final Act. Charter 77 pointed out that the Czechoslovak regime was violating the very rights it had solemnly pledged to respect in Helsinki. The communist authorities responded with anger – detaining the manifesto’s organizers – but the genie was out of the bottle. In a remarkable display of region-wide solidarity, Hungarian intellectuals clandestinely declared support for Charter 77, stating “the defense of human and civil rights is a common concern of all Eastern Europe”. Despite arrests and harassment, the movement for human rights spread across borders, united by the language of Helsinki.

Poland proved to be particularly fertile ground for this burgeoning dissent. Even before Helsinki, Poles had a history of restive public opinion and worker protests, in 1956 and 1970. Now, Helsinki’s principles emboldened opposition intellectuals and workers alike to push back against the regime’s failures. In 1976, the Workers’ Defense Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników, KOR) was established in Poland, initially to aid persecuted labor protesters, but soon it evolved into a broader human-rights network. KOR’s founders – including Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik – explicitly embraced human and civil rights as their cause. They published open letters citing Poland’s international commitments and constitutional rights, thereby implicitly invoking Helsinki’s spirit. By the late 1970s, a nascent “democratic opposition” had formed in Poland, comprised of intellectuals, students, Catholic activists, and dissident factory workers, all “founded on the grounds of human rights” and demanding those rights be honoured.

Western societies took note of these developments. In the United States, private citizens formed Helsinki Watch committees to support Eastern bloc dissidents and publicize their plight. These efforts would eventually grow into the global NGO known as Human Rights Watch. Meanwhile, the CSCE process itself continued: follow-up conferences in Belgrade (1977–78) and Madrid (1980–83) provided forums where Western diplomats could pointedly question Eastern governments about their human rights records. This review mechanism – essentially a diplomatic shaming process – gave dissidents additional leverage. For the first time, Soviet-bloc leaders found themselves internationally accountable, at least politically, for how they treated their own citizens. The Helsinki Final Act, though non-binding, had created a normative weapon. Dissidents wielded it to embarrass their regimes and inspire their compatriots, while Western officials and media amplified the message.

Solidarity in Poland: From Shipyard Strikes to a National Movement

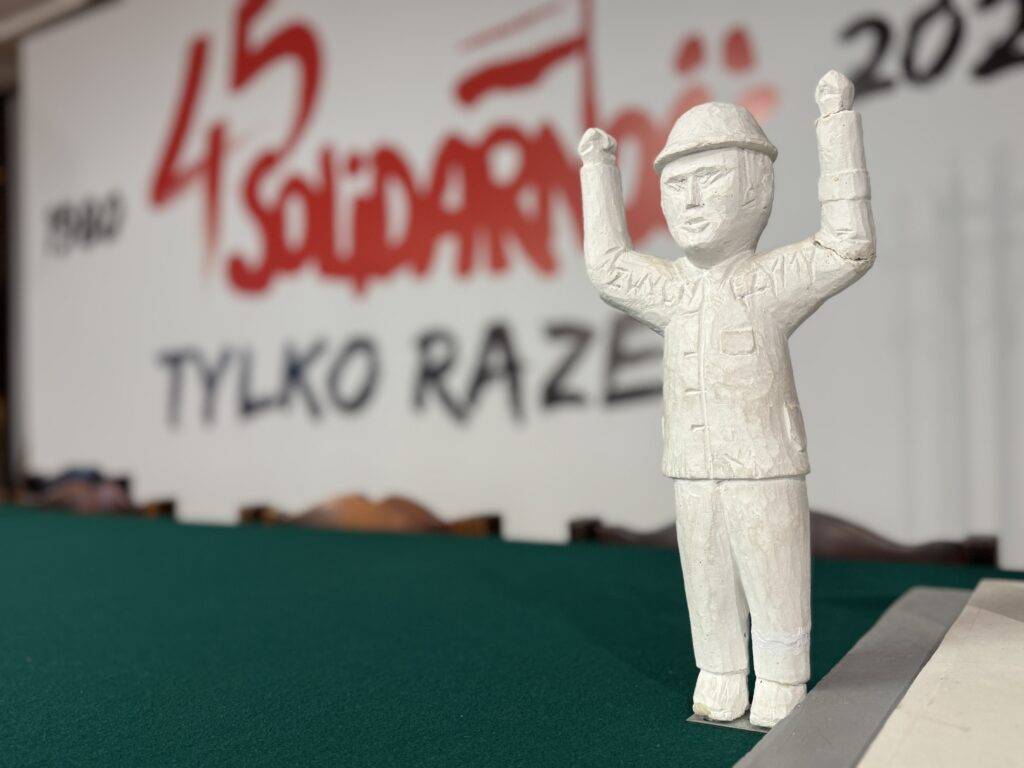

The most dramatic manifestation of the Helsinki Accords’ unintended power came in Poland in 1980. By that year, Poland’s economy was in crisis, and popular discontent was boiling over. In August 1980, workers at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk went on strike over sudden price hikes and poor conditions. What might have been a routine labour dispute under a repressive system instead escalated into a nationwide social revolution, thanks to an extraordinary alliance between workers and intellectual dissidents. As one historian described, “the harbinger of the fall of the Soviet empire took place in Poland in 1980, with the rise of Solidarity, simultaneously a trade union and mass political movement that united democratic dissidents with Polish shipyard and factory workers.”

At the Lenin Shipyard, the workers – led by an electrician named Lech Wałęsa – formulated 21 demands to present to the communist authorities. Tellingly, these went far beyond bread-and-butter issues. The very first demand was the right to form free and independent trade unions – a direct challenge to the Party’s monopoly and an embodiment of basic freedom of association. Other points called for freedom of expression, the release of political prisoners, and adherence to Poland’s own constitutional liberties. In essence, the workers were insisting that their government honor the rights it had promised in Helsinki. The Inter-Factory Strike Committee even painted these 21 demands on plywood boards and hung them on the shipyard gate for all to see, symbolizing a new era of openness.

As the strike spread to other enterprises and cities, Poland’s re-energised intellectual opposition joined forces with the workers. Seasoned KOR activists and Catholic figures provided advice and communication channels. Outside the shipyard gates, a flowering of free speech took place – pamphlets, speeches, even public Masses were held for the striking workers. The “Helsinki ethos” – that fundamental rights were universal and non-negotiable – permeated the movement’s rhetoric. One popular slogan painted on a banner was “Nie ma wolności bez Solidarności” (“There is no freedom without Solidarity”) – capturing the movement’s blend of social and political liberation aims.

On 31 August 1980, after weeks of standoff, the regime gave in. The Gdańsk Agreement was signed, meeting many of the strikers’ key demands. For the first time in the Soviet bloc, an independent trade union – aptly named Solidarity (Solidarność) – was born. At its peak, Solidarity would have nearly 10 million members, a quarter of Poland’s population. It was a phenomenon: a self-organized, non-violent mass movement campaigning for workers’ rights, civic freedoms and national dignity. And it had sprung to life without any violent insurrection, under the noses of a communist regime that had just five years earlier signed an international accord upholding “freedom of thought” and “freedom of belief”.

Solidarity’s emergence sent shockwaves through the Eastern bloc. Moscow’s worst fear – that “hostile” ideas from Helsinki would spark an ideological offensive – appeared to be coming true in Poland. In truth, Solidarity was driven by native Polish grievances and inspirations, including the uplifting influence of Polish Pope John Paul II’s 1979 visit, but Helsinki’s impact was evident in the movement’s language and legitimacy. Here were Polish citizens openly talking about human rights, free unions, democracy and truth – concepts bolstered by the Final Act and now firmly planted in the political discourse. The communist authorities, predictably, viewed Solidarity as an existential threat. Under pressure from the Kremlin, General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s government declared martial law in December 1981, banning Solidarity and jailing its leaders. The crack-down was harsh; tanks rolled into Polish cities and the brief “Helsinki Spring” in Poland was forced back underground. But the impact of Solidarity could not be erased so easily. The Polish people had experienced 16 months of unprecedented freedom, self-organization and truth-telling, and the memory would smoulder on. A government that had once trumpeted the Helsinki conference now had to surround shipyards with barbed wire and imprison activists for quoting the Final Act – a stark illustration of how far the regime had fallen from the high ideals it signed onto in 1975.

From Solidarity to the Fall of the Eastern Bloc

Throughout the 1980s, the spirit of Helsinki and the example of Solidarity continued to undermine communist authority across Central and Eastern Europe. Though repressed, Solidarity lived on as an underground organization, supported by clandestine publications and the morale-boosting broadcasts of Radio Free Europe. Crucially, Western countries maintained pressure: at follow-up CSCE conferences, Western diplomats persistently raised the issue of Poland and human rights violations, preventing the matter from being swept aside. Meanwhile, Helsinki committees kept up their advocacy. Even in martial-law Poland, an underground Helsinki Committee formed in 1982 to document the regime’s abuses and smuggle reports to the West. The Soviet Union’s own reformist leader from 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev, introduced policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) that inadvertently gave further space to the long-suppressed civil societies in the bloc. By the late 1980s, the grip of communism was visibly weakening.

Poland once again led the way. In 1988, a fresh wave of labour strikes (inspired in part by economic desperation and the ever-present ideal of Solidarity) forced the regime to the negotiating table. What followed was the historic “Round Table” talks of early 1989, where the communists agreed to legalize Solidarity and hold semi-free elections. When those elections took place in June 1989, Solidarity won overwhelmingly – a stunning, peaceful transfer of power that would have been unimaginable without the groundwork laid by the movement over the previous decade. As former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Daniel Fried observed, “the communist system in Poland never really recovered [after Solidarity’s rise], and in 1989 the entire communist system in Eastern Europe collapsed.”

Indeed, Poland’s breakthrough triggered a domino effect across the region in 1989 – annus mirabilis. Hungary opened its border and began democratising; East Germans, long kept prisoner by the Berlin Wall, flooded through to the West via Hungary and Czechoslovakia; the East German regime crumbled, leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Czechoslovaks staged the peaceful Velvet Revolution; Bulgaria and Romania ousted their hardline leaders. By the end of 1989, one after another, the communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe had either negotiated themselves out of power or been swept away by popular revolt.

The Helsinki Final Act did not single-handedly cause the collapse of communism – many factors were at play, from economic decay to the reformist winds from Moscow. But Helsinki was a critical accelerant of change. It encouraged and legitimized dissent, gave activists a common language of rights, and created channels of international solidarity. What began in 1975 as a Soviet-driven bid to freeze geopolitical realities ended up, in the words of one scholar, “a catalyst of the 1989 regime change” in Eastern Europe. The Accords, especially the human rights commitments, “provided grounds for demanding human rights, putting pressure on the states of the Eastern Bloc”, and even pressured Western nations to confront those abuses rather than ignore them. Dissidents acted more boldly “than would otherwise have been possible,” knowing the world was watching. In a delicious historical irony, the Soviet Union essentially signed a document that, a decade and a half later, helped seal the fate of its dominion in Eastern Europe. As the Cold War drew to a close, leaders East and West acknowledged the importance of what had happened in Helsinki. The 1990 Charter of Paris – signed by the now-free Eastern European states, the USSR, and the West – explicitly built on the “principles of the Helsinki Final Act” to declare a new era of democracy and unity in Europe. It was the formal obituary of the Iron Curtain – an outcome far beyond the imagination of those in Finlandia Hall back in 1975.

Helsinki’s Unintended Triumph and NATO’s Gratitude

The unintended triumph of the Helsinki Accords reshaped the global balance of power. The collapse of one-party communist rule in Eastern Europe not only freed millions from authoritarian control – it also expanded the realm of Western democracy and security. During the 1990s and 2000s, the formerly captive nations of Central and Eastern Europe eagerly joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union, anchoring themselves in the institutions of the free world. NATO, originally an alliance formed to contain the Soviet threat, found itself welcoming new members from the former Warsaw Pact. Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic entered NATO in 1999; the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and others followed in the early 2000s. This eastward enlargement of NATO would have been unthinkable without the chain of events set in motion by the Helsinki conference. By agreeing in 1975 to respect their peoples’ rights, the communist regimes sowed the seeds of their own collapse – and the West reaped the strategic benefit when those nations chose a future aligned with NATO.

Today, NATO and its member states – especially those who endured decades under Soviet domination – have ample reason to be “extremely grateful” for the Helsinki Conference of 1975. The “Spirit of Helsinki” demonstrated that dialogue and principles can achieve what tanks and threats cannot. It was human rights – a seemingly soft instrument of foreign policy – that ultimately proved to be a battering ram against an empire, by empowering ordinary people to claim their freedom. That lesson is not lost on NATO’s newest members. Poland and the Baltic countries, for example, remain among the most vocal defenders of the post-Cold War order of peace and democracy in Europe. They remember that their own independence was won not on the battlefield, but through persistence, unity, and the moral leverage that international norms provided. This is why, faced today with a resurgent aggressive Russia, these countries are relentless in fortifying their defenses and insisting on a firm Western response. They know what is at stake. They echo the principles first laid down in Helsinki – the inviolability of borders, the sovereignty of nations to choose their alliances, and the fundamental rights of peoples – because those principles safeguarded their liberty.

When Russia launched a brutal war against Ukraine in 2022, violating its neighbour’s territorial integrity, it starkly breached the Helsinki Final Act’s core tenets: No use of force, Respect for frontiers. No one has been more strident in condemning that aggression than Poland and the Baltic states. Their stance is born of history: they once lived under Moscow’s hegemony and fought their way to freedom, aided by the very “Helsinki effect” that Russia now chooses to discard. It is telling that in 2025, on the 50th anniversary of the Helsinki Accords, Finland – a country that hosted the 1975 meeting and remained neutral in the Cold War – has joined NATO and chairs the OSCE, calling for a return to the true spirit of Helsinki in resolving conflicts. The legacy of 1975 thus lives on, as both a caution and an inspiration.

Signatory states at the OSCE 1975

- Austria

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Cyprus

- Czechoslovakia

- Denmark

- Finland

- France

- East Germany

- West Germany

- Greece

- Holy See

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Italy

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Monaco

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- San Marino

- Soviet Union

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Yugoslavia

Heads of state or government in Helsinki 1975

- Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Erich Honecker, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

- Gerald Ford, President of the United States

- Bruno Kreisky, Chancellor of Austria

- Leo Tindemans, Prime Minister of Belgium

- Todor Zhivkov, Chairman of the State Council of Bulgaria

- Pierre Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada

- Makarios III, President of Cyprus

- Anker Jørgensen, Prime Minister of Denmark

- Carlos Arias Navarro, Prime Minister of Spain

- Urho Kekkonen, President of Finland

- Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, President of France (who also serves as Co-Prince of Andorra however no such function at all is mentioned in the declaration)

- Harold Wilson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- Konstantinos Karamanlis, Prime Minister of Greece

- János Kádár, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party

- Liam Cosgrave, Taoiseach of Ireland

- Geir Hallgrímsson, Prime Minister of Iceland

- Aldo Moro, Prime Minister of Italy

- Walter Kieber, Prime Minister of Liechtenstein

- Gaston Thorn, Prime Minister of Luxembourg

- Dom Mintoff, Prime Minister of Malta

- André Saint-Mleux, Minister of State of Monaco

- Trygve Bratteli, Prime Minister of Norway

- Joop den Uyl, Prime Minister of the Netherlands

- Edward Gierek, First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party

- Francisco da Costa Gomes, President of Portugal

- Nicolae Ceaușescu, President of Romania

- Gian Luigi Berti, Captain Regent of San Marino

- Agostino Casaroli, Cardinal Secretary of State

- Olof Palme, Prime Minister of Sweden

- Pierre Graber, President of the Swiss Confederation

- Gustáv Husák, President of Czechoslovakia

- Süleyman Demirel, Prime Minister of Turkey

- Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Josip Broz Tito, President of Yugoslavia

International organisations

- Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations (giving the opening speech “as their guest of honour”, non-signatory)

Read More:

- University of Minnesota Human Rights Library – “Final Act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (Helsinki Final Act), 1975”

- Atlantic Council (Daniel Fried) – “Fifty years later, the Helsinki process stands as a turning point for human rights in Europe”

- Blinken OSA Archivum (Miklós Zsámboki) – “Unintentional Effect: the 45th Anniversary of the Helsinki Accords”

- U.S. Department of State – Office of the Historian – “Helsinki Final Act, 1975”

- Wikipedia: Helsinki Accords

- Archivum: Unintentional Effect: the 45th Anniversary of the Helsinki Accords

- Culture.pl: Poland’s Walk To Freedom in 13 Iconic Photos

- University of Minnesota: The Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Aug. 1, 1975, 14 I.L.M. 1292 (Helsinki Declaration)

- HFHR: Helsinki Committee in Poland

- Wilson Center: The Enduring Spirit of Helsinki: Finland Becomes OSCE Chair for 50 Years of Helsinki Final Act

- Wikipedia: Solidarity (Polish trade union)