Drones have gone from gimmick to game-changer. In Ukraine, swarms of cheap UAVs now stalk everything from tanks to individual soldiers. Saab’s answer is a stripped-down drone killer designed for the battlefield’s new reality. The race is on: as RUSI observes, Russia today boasts “the most formidable counter-UAS capabilities on earth”.

These cheap uncrewed systems—often costing only a few hundred euros—can scout targets or drop precision munitions, and they have inflicted heavy losses on both equipment and troops. This dramatic rise in drone warfare has demonstrated an urgent need for effective and cost-efficient countermeasures. How prepared are modern armed forces to face this new drone-saturated battlespace? And how can they defend against a drone flood without breaking the bank?

Improvised Defences: From ‘Cope Cages’ to Log Armour

The first responses to the drone threat were often improvised. Both Russian and Ukrainian crews resorted to DIY modifications of their vehicles in an attempt to survive lethal drone strikes. On the frontlines, makeshift metal cages – colloquially dubbed “cope cages” – have been welded atop tank turrets to intercept incoming grenades or loitering munitions. Some vehicles are draped with nets or festooned with wooden sticks, giving them a bizarre, Mad Max-like appearance. These ad-hoc cages are meant to detonate drone warheads at a distance or even ensnare the drone itself before it hits the armour.

Russian troops took this improvisation further by literally armouring their vehicles with wood. In several instances, logs have been stacked on the flanks of self-propelled howitzers and older armoured vehicles to absorb explosive blasts. Tank crews even built “log walls” on top of the cages in hopes of stopping drones from striking the sides. These early measures provided a psychological comfort but limited physical protection – perhaps reducing damage from small drone shrapnel – but unsurprisingly, they proved ineffective against modern anti-tank munitions and explosive charges. Military analysts have noted that such barbecue cage armour and timber shielding do little against direct hits by anti-tank missiles or larger drone munitions and may even impair vehicles by adding weight and reducing mobility. But they are quite effective against small drones, which is the main frontline threat.

Yet, the improvisation highlighted a key point: drones had changed the battlefield, and militaries were scrambling to adapt. What began as desperate field expedients by Russian units suffering drone strikes in 2022 soon became widespread. By 2023, both sides were covering everything from tanks to all-terrain buggies in cages and mesh. Ukrainian troops, for example, have shielded some of their Western-supplied howitzers with elaborate cages, while Russian units started mounting factory-made cage kits on new T-80 tanks rolling off the production line. In essence, the proliferation of these DIY defences speaks volumes about the dominance of drones on today’s battlefield – and the lack of ready-made solutions at the outset of the war.

Components of a Modern Counter-Drone Defence

Ad-hoc cages and log armour are no substitute for a proper Counter-Unmanned Aircraft System (C-UAS) defence. A modern Ground-Based Air Defence (GBAD) system designed to defeat drones consists of three core components, often described as the eyes, brain, and muscle of the system:

- Sensors – the “eyes”: Advanced sensors, particularly 3D radars and electro-optical detectors, are needed to spot and track small drones. Modern short-range air defence radars like Saab’s Giraffe 1X can detect and classify very small, low-flying targets – even those with a radar cross-section under 0.01 m², about the size of a bird. Such sensitive sensors generate a vast stream of data, which must be processed quickly to distinguish drones from clutter. This is where the “brain” comes in.

- Command and Control (C2) – the “brain”: A robust C2 system acts as the brain of C-UAS, fusing sensor data and providing a real-time operating picture. Modern battle management systems increasingly leverage artificial intelligence to analyse drone flight patterns in fractions of a second and assist human operators. High situational awareness is crucial: it enables rapid decisions on how to counter an inbound drone and selects the appropriate effector to neutralise it.

- Effectors – the “muscles”: The effector is the active countermeasure – it could be a “soft-kill” system that disrupts the drone, or a “hard-kill” weapon that destroys it. Effectors range widely from electronic jammers and laser dazzlers to anti-drone missiles, guns, or even interceptor drones. The choice of effector often depends on the scenario: Is it peacetime or frontline combat? Is the drone a lone quadcopter or a swarm of military-grade unmanned aerial vehicles UAVs? Each threat may demand a different tool.

Soft Kill vs Hard Kill Approaches

In C-UAS doctrine, there are two fundamental approaches to neutralisation: soft-kill and hard-kill. A soft-kill disrupts or disables the drone without physical destruction – for example, jamming its radio signals, hacking its control link, or using dazzling lasers and microwave weapons to fry its circuits. A hard-kill, by contrast, physically destroys the drone – whether by gunfire, missile, or a kamikaze “hunter” drone that crashes into the target. Both approaches have roles, and often a layered defence will employ both in tandem.

Soft-kill methods can be cost-effective and avoid debris falling on friendly areas, important for civilian settings, but they may struggle if drones are autonomous or heavily hardened against jamming. Hard-kill methods are more kinetic and final but often raise the issue of cost asymmetry. Indeed, a recurring challenge in drone defence is economic: It makes little sense to use a million-euro missile to shoot down a €500 drone. During one incident, an allied force infamously downed a simple hobby drone with a Patriot surface-to-air missile – a €5 million missile for a €200 target.

Such lopsided exchanges are clearly unsustainable if repeated at scale. “The cost ratio remains a challenge,” explained Per Järbur to Nordic Defence Review, the Swedish approach. Järbur, an air defence expert at Saab, noted that while a commercial drone might cost only a few hundred euros, high-end air defence interceptors cost vastly more. This has spurred interest in cheaper countermeasures, like electronic warfare, or novel interceptors such as net launchers and drone catchers. Saab, for instance, foresees “hunter drones” – drones that can chase and physically tackle enemy drones – becoming an important tool in the coming years, alongside jamming and even anti-drone nets. The ideal is to develop a spectrum of options so that each hostile drone can be countered in the most cost-efficient way available – using an inexpensive jammer or interceptor drone against low-end threats, reserving missiles for the high-end ones.

Rapid Innovation: The Saab “Loke” C-UAS in 84 Days

Facing the drone onslaught in Ukraine, it’s clear that defenders must innovate as fast as the attackers. In fact, on the Ukrainian battlefield, tactics and technology for drones are evolving every few months. To keep up, countermeasures need to be developed in weeks, not years. A noteworthy example of such rapid innovation is the Swedish project “Loke”, a mobile counter-drone system created in collaboration between Saab, the Swedish Air Force and the FMV (Defence Materiel Administration). In an unprecedented sprint, the Loke concept went from idea to working prototype in just 84 days.

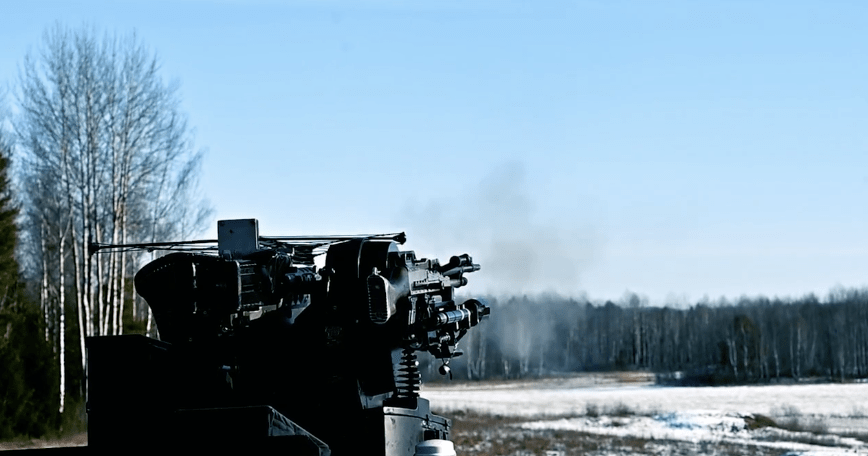

What Saab and its partners achieved with Loke is essentially a “frugal innovation” model for C-UAS. Instead of a traditional multi-year development cycle, they repurposed off-the-shelf components to build a functional system in under three months. Engineers took proven pieces – the Giraffe 1X radar for surveillance, a Trackfire remote weapon station – with a small calibre auto-cannon – for kinetic effect, plus a lightweight C2 software – and integrated them on a standard Sisu 4×4 military truck. They even tested some gear in decidedly ad-hoc fashion: at one point Saab’s team strapped the 150-kg Giraffe radar to a wooden pallet with bungee cords to validate it under field conditions. It wasn’t pretty – more “tactical DIY” than glossy defence contractor chic – but it worked. During trials, the Loke prototype successfully detected and shot down dozens of test drones, 36 quadcopters and 17 fixed-wing targets, using its rapid-fire gun.

The Loke system covers the entire kill chain: it can spot low, slow drones with the 3D radar, identify/classify them via the C2, and then cue the effector, gun or other, to shoot them down – all while being mobile and fairly small. It’s also modular and scalable by design. Saab notes that Loke can be easily upgraded with additional sensors (like infrared cameras or more radars) and additional effectors (say, a jammer or a bigger missile) as threats evolve. Notably, the whole system is built on a compact vehicle and can even operate on the move, meaning a unit equipped with Loke can keep itself protected from drones while relocating. This is a crucial feature on dynamic fronts like Ukraine, where staying still for too long invites enemy drone strikes.

Swedish Air Force officials have lauded Loke’s development as a model for future procurement. Major General Jonas Wikman, Chief of the SwAF, highlighted that “we are prepared to deviate from normal processes to meet today’s threats quickly”. Indeed, Loke’s success is now held up as “rapid acquisition” best practice – showing NATO allies that it is possible to field effective counter-drone capabilities in months through ingenuity and partnership, rather than wait years for perfection. As one Saab executive put it, “we had to think outside the box… by repurposing existing products and integrating new features, we implemented the concept in record time.” The choice of the name “Loke” (Loki, the Norse trickster god) is fitting – this little system was devised as a mischievous answer to the new drone threat, put together faster than the bureaucracy could say “procurement cycle”.

While Loke was developed with Sweden’s needs in mind, commentators have been quick to note its relevance to Ukraine and other conflict zones. A NATO member innovating in real time provides exactly the kind of solution Ukraine’s forces could benefit from. Some analysts even dubbed Loke a “DIY drone killer perfect for Ukraine,” arguing that its blend of simplicity, speed, and effectiveness is ideal for an army facing constant swarm attacks. Whether Loke or similar systems end up in Ukrainian hands, the project sends a larger message: innovation at startup-like speeds is now a necessity in modern war. In Ukraine, Russia and NATO alike, whoever can adapt minute by minute has the edge.

Responses from Russia, China, and Others

The scramble to counter drones is not limited to Ukraine and its Western backers. Russia, having felt the sting of Ukraine’s TB2 drones and countless smaller UAS, has heavily invested in counter-drone measures of its own. In fact, according to a RUSI analysis, the Russian forces now field “the most formidable counter-UAS capabilities on earth” at the tactical level. Over the last three years, Russia has layered its battlefield with electronic warfare (EW) units, jamming devices, and short-range air defences down to the company level. Their vehicles and dugouts bristle with ubiquitous netting, wire mesh, and foam padding to absorb drone blasts. Electronic countermeasures – from backpack jammers to larger systems – attempt to suppress Ukrainian drones’ control signals or navigation. Russian soldiers now routinely receive training on drone awareness, learning techniques to spot and shoot down small drones with rifles or machine guns if needed. Even Russian airbases far behind the front are being rapidly hardened with physical barriers and EW coverage to blunt long-range drone strikes – like those from Ukrainian-modified Shahed “Geran” drones. These efforts have paid dividends: by some accounts, only a small fraction of the drones launched by Ukraine now survive to hit their targets, as Russian countermeasures improve. In short, Moscow’s forces have treated drone defence as a top priority – and they are continuously learning and adapting. If a NATO military were to face Russia directly, it would likely encounter an enemy well-versed in countering uncrewed systems, honed by years of facing Ukraine’s inventive drone tactics.

China, too, has taken note of the drone revolution and is aggressively upgrading its counter-UAV technology. Recent reports show the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) adopting a multi-layered defence approach integrating electronic warfare, directed-energy weapons (lasers, high-power microwaves), and AI-driven interceptors. Chinese exercises last year revealed shortcomings, with traditional SAMs only stopping ~40% of inbound drones, prompting a rethink. Now, China’s domestic industry boasts 3,000+ anti-drone equipment manufacturers, and the government’s procurement of C-UAS systems has surged – 205 contracts in 2024, up from 87 in 2022. Notable Chinese innovations include the NORINCO “Hurricane-3000” – a high-power microwave emitter likened to “launching thousands of microwave ovens into the sky” – which can fry drone electronics across a 3 km radius in milliseconds. A smaller mobile version, the Hurricane-2000, is vehicle-mounted, aiming to bring this area-effect weapon to the field. Alongside microwaves, China has fielded laser weapons like the Silent Hunter, a 30 kW fibre laser that can burn through drones up to 4 km away – Saudi Arabia even imported Silent Hunter units to counter hostile UAVs. Chinese firms AVIC and CASIC have their own laser interceptors (Light Arrow, LW-30, etc.), and the PLA is integrating these with radar/EO networks under systems like the “Sky Dome” (Tianqiong) – a command system that fuses radar tracking with jamming and laser firing in one automated loop. Beijing’s clear goal is to dominate the low-altitude battlespace by detecting drones early and engaging them cheaply, en masse and at scale. The Chinese strategy underscores how seriously major powers are treating the drone threat – not just by building more drones, but by building the means to neutralise more drones.

Iran, for its part, is known more for exporting drones than for shooting them down, but its influence is felt in this arena too. Iranian-made Shahed-136 loitering drones (rebranded “Geran-2” by Russia) have rained on Ukrainian cities, forcing Ukraine and NATO to rush in counter-drone aid. Western allies have supplied Kyiv with various C-UAS assets to counter the Iranian drones – from Lithuanian SkyWiper anti-drone guns to vehicle-mounted jammers and short-range air defences. Israel – always alert to Iranian drone threats via proxies – has developed the Iron Beam laser and improved its Iron Dome system to shoot down small UAVs, a technological feat closely watched by NATO. Meanwhile, Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE have invested in electronic defences and imported systems, such as the Chinese lasers, after suffering drone and missile attacks from Iranian-aligned groups. In essence, Iran’s proliferation of drones has spurred a parallel growth in countermeasures among its adversaries.

At a NATO level, strategic thinking has shifted markedly in the past two years. NATO militaries no longer see drones as just a niche threat; they acknowledge that drone warfare is here to stay. The alliance has begun developing a common counter-drone doctrine, and in 2024 NATO held large exercises in Europe to test interoperable C-UAS technology among 15 member states. The aim is to identify “optimal C-UAS architectures, common requirements, and technical interoperability standards” for joint air defence. NATO has also activated its first joint procurement contracts for C-UAS gear – for example, a framework to let allies buy the Danish MyDefence Wingman drone detection system and DroneShield jamming guns was launched in mid-2024. This allows even smaller allied armies to quickly field proven tech against the proliferating drone threat. There is recognition that no single country can tackle this alone: a truly effective defence may require integrating sensors and shooters across nations, much as NATO integrated air defences against manned aircraft during the Cold War. Still, as Saab’s Per Järbur observes, while joint NATO air defence against drones is necessary, “the alliance has a way to go to achieve this”. Every nation is focused firstly on the drones menacing its own troops, and aligning dozens of countries on a common solution remains a work in progress.

Tanks, Drones and the Future of Warfare

The advent of widespread drone warfare led some to claim that traditional land platforms, especially tanks, were now obsolete. Dramatic videos from conflicts like Nagorno-Karabakh (2020) and early in the Ukraine war showed tanks being picked off from above by UAVs, fuelling theories of a new era where “drones reign supreme” and heavy armour becomes a thing of the past. However, a closer analysis – and the hard lessons from Ukraine – suggest a more nuanced reality. Tanks are not obsolete; rather, they must adapt. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated that while drones are indeed a potent new threat, they have not made well-supported tanks irrelevant on the battlefield. In the ongoing conflict, both Russia and Ukraine continue to deploy tanks and request more of them. Ukrainian forces, for instance, still rely on tanks for breakthrough attempts and defensive firepower, and Russia has pulled older T-64 and T-72s out of storage to refill its armoured units.

The key is combined arms. When tanks are used with infantry protection, air defence, electronic warfare and now anti-drone measures, they once again can be highly effective and survivable. Many Russian tanks in Ukraine, despite being targeted by everything from Javelin missiles to drone-dropped bombs, have shown an ability to protect their crews, especially newer models with upgraded armour. Conversely, tank losses early in the war were largely due to poor tactics – charging without infantry or air cover – rather than an inherent flaw in tanks themselves. In fact, Western defence experts note that NATO tanks have much better crew protection and would never operate in the disjointed manner Russian units did in 2022. Thus, while drones demand changes – like active protection systems on tanks to shoot down incoming missiles and drones, or the cage armour as a stop-gap – they do not spell the end of the tank. A recent British analysis bluntly concluded that “drones have not made tanks obsolete… upgraded armour is still in the fight”. Modern armies will likely invest in both: more drones and more resilient armoured vehicles.

As one War on the Rocks commentary put it, “while the threats facing tanks have grown, so have the countermeasures.” Drones are just another threat that tanks and other legacy systems must be equipped to handle – just as they adapted to anti-tank guided missiles in the past. Those adaptations are underway: tanks are being outfitted with electronic jammers, radar-guided active defences, and improved top armour to defeat drone strikes. Even simple tricks help – Ukrainian tankers sometimes drape camouflage netting over their tanks to confuse the view of overhead drone operators, and Western tanks arriving in Ukraine have added kevlar liners and fire suppression to mitigate loitering munition hits. The consensus among NATO strategists is that future forces will blend uncrewed systems with traditional firepower, not replace one with the other. Justin Bronk of RUSI warns that over-reliance on swarms of small drones, at the expense of artillery and airpower, could actually play into Russia’s hands, given Moscow’s strong counter-drone defences. Instead, drones should enhance the old weapons: providing better reconnaissance, targeting and some additional strike capacity, while tanks, artillery and fighters continue to deliver decisive blows in ways drones alone might not. In essence, the tank-versus-drone debate has settled on a middle ground – the tank is still very important when used smartly, and drones are now indispensable knights on the chessboard, but neither can checkmate the enemy alone.

A Layered Defence and Speed Are Key

If there is one takeaway from the drone wars in Ukraine, it is that there is no silver bullet. “There is no such thing as the perfect C-UAS system that can defend against all threats. Not today, and not in the future,” as Saab’s Per Järbur aptly put it. Drones come in too many shapes and sizes – from tiny quadcopters buzzing at treetop level to large kamikaze drones diving from 5-62 kilometres up – for any single defence to catch them all. Therefore, militaries must adopt a layered defence: multiple systems working together, each covering the gaps of the others. Radar-guided guns can tackle some drones, electronic jammers might stop others, and short-range missiles will handle those that sneak past. No one measure is foolproof, but a combination can provide comprehensive coverage. Nations and armed forces need to analyse their specific threat environment – the types of drones they face, the terrain, the likely swarm tactics – and then deploy a tailored mix of countermeasures. A front-line army unit facing swarms of explosive FPV drones will need a very different C-UAS loadout – perhaps mobile gun trucks like Loke, and signal jammers – compared to, say, an airport authority worried about the odd rogue hobby drone, which might rely on police drones and geo-fencing software. There is no one-size-fits-all.

Another clear lesson is the importance of speed and agility. Technology is evolving at breakneck pace in the drone domain. As one Ukrainian commander wryly observed, the enemy’s drone tactics and models seem to change “every 3–4 months”. This means countermeasures must develop at least as quickly – or faster. Traditional procurement, which can take years to field a new system, simply cannot keep up with a threat that mutates in weeks. Close cooperation with industry and even small startups is vital to inject new tech quickly. Saab’s approach with Loke – repurposing existing kit in innovative ways – is one template. Another is the use of open architectures in C-UAS systems, so that if a new sensor or effector emerges, it can be plugged into the network without starting from scratch. NATO’s efforts to define common standards also play into this agility, by ensuring allies’ systems can share data and tactics swiftly.

Cost will remain a driving factor. It’s not enough to have effective countermeasures; they also need to be affordable and scalable. Using €1000 anti-drone drones to defeat €500 attack drones is a much better equation than using €3 million missiles for the same job. Advances in directed-energy weapons, lasers and microwaves, are promising in this regard – they offer a theoretical cost-per-shot of only a few dollars’ worth of electricity, making them highly economical for knocking down swarms, provided the technology matures to handle battlefield conditions. Likewise, electronic warfare, though not glamorous, often provides the cheapest per-engagement cost. The ideal future C-UAS arsenal might see high-end interceptors saved for only the most dangerous targets, like a large armed UAV or cruise missile, while the bulk of smaller drones are dispatched by cheaper means such as jammers, lasers or interceptor drones. Achieving an optimal “cost-per-kill” ratio will be essential, military planners note, to avoid bankrupting oneself against an enemy’s bargain-basement drone armada.

Finally, training and doctrine must evolve alongside hardware. Stopping drones is not purely a technical problem but also a tactical one. Troops need to learn new drills – for example, how to conceal their positions from drone observation, how to react when a buzzing quadcopter appears overhead, and how to coordinate electronic and kinetic fires against a swarm. NATO armies are now incorporating counter-drone scenarios into their exercises, and Ukraine has been a harsh but valuable teacher in these tactics. In the same vein, better inter-alliance coordination is called for. A drone does not respect borders; NATO’s vision of joint air defence will require nations to share sensor data and perhaps even delegate engagement authority in certain situations, similar to how integrated NATO air defence worked against manned aircraft. While national interests and bureaucratic hurdles remain, the increasing drone threat is fuelling cooperation, as seen in joint development programmes and intelligence sharing on drone technologies.

Conventional Arms Are Not Obsolete

The rise of drones on the battlefield has been as disruptive as it is visible. Ukraine’s conflict has showcased both the immense potential of unmanned systems and the frantic efforts needed to counter them. It has been a stark reminder that in warfare, for every new Killer App (in this case, cheap drones), a countermeasure must be found or invented. From the early days of slapdash Cope Cages and wooden armour, we are now seeing sophisticated anti-drone networks spring into action – combining radar eyes, AI brains, and a mix of hard and soft muscles to swat drones from the sky. Defensive systems like Saab’s Loke demonstrate that with urgency and creativity, it is possible to innovate at a pace that matches the threat. At the same time, the experiences of Russian and Ukrainian forces highlight that drones have not made conventional arms obsolete; instead, they force those arms to get smarter and better protected. In NATO capitals, strategists now talk of Composite Warfare – blending traditional firepower with swarming drones, and equally, pairing old armour with new anti-drone shields. There is no room for complacency. As one NATO report put it, “technically, a lot is possible – speed is the key.” Future battlefields will likely see even more drones, in even more innovative roles, from autonomous drone swarms to AI-guided loitering missiles. Combating this drone flood will require a continual cycle of adaptation. No single system or one-off solution will suffice; success will come from an agile, layered defence that can absorb new technologies and tactics as fast as they emerge. In the end, warfare is a relentless contest of move and counter-move. Drones opened a new front in that contest – and now the world’s militaries are racing to ensure that when the drones come flying, they will be ready, eyes on the sky and tools in hand, to shoot them down or shut them down before they wreak havoc. The drone war is here, but so too is the drone counter-war – and it may very well decide the future of armed conflict.

Read More:

- Rusi: NATO Should Not Replace Traditional Firepower with ‘Drones’

- SAAB: From concept to impact – Saab and the Swedish Air Force Deploy “Loke”

- United24: Wooden Armor: Russia’s DIY Desperate Tactics to Survive Ukrainian Drone Attacks

- BFBS: Ukrainian drones use double-tap attack to defeat Russian tanks fitted with metal cages

- Defense One: China’s counter-UAV efforts reveal more than technological advancement

- War On The Rocks: The Tank Is Not Obsolete, and Other Observations About the Future of Combat

- TWZ: Russia Adds Anti-Drone ‘Cope Cages’ To All-Terrain Buggies, Motorcycles

- Business Insider: Images Show Wild Vehicle Cage Armor for Drones in Ukraine War

- Janes: Swedish Air Force, FMV, and Saab fuse together ‘Loke’ C-UAS in 84-day development dash

- Wes O’Donnell: Sweden’s DIY Drone Killer “Loke” is Perfect for Ukraine

- Breaking Defense: NATO activates first small C-UAS contract as allies target drone proliferation threat

- The Telegraph: Tanks remain kings of the battlefield. Drones have not made them obsolete