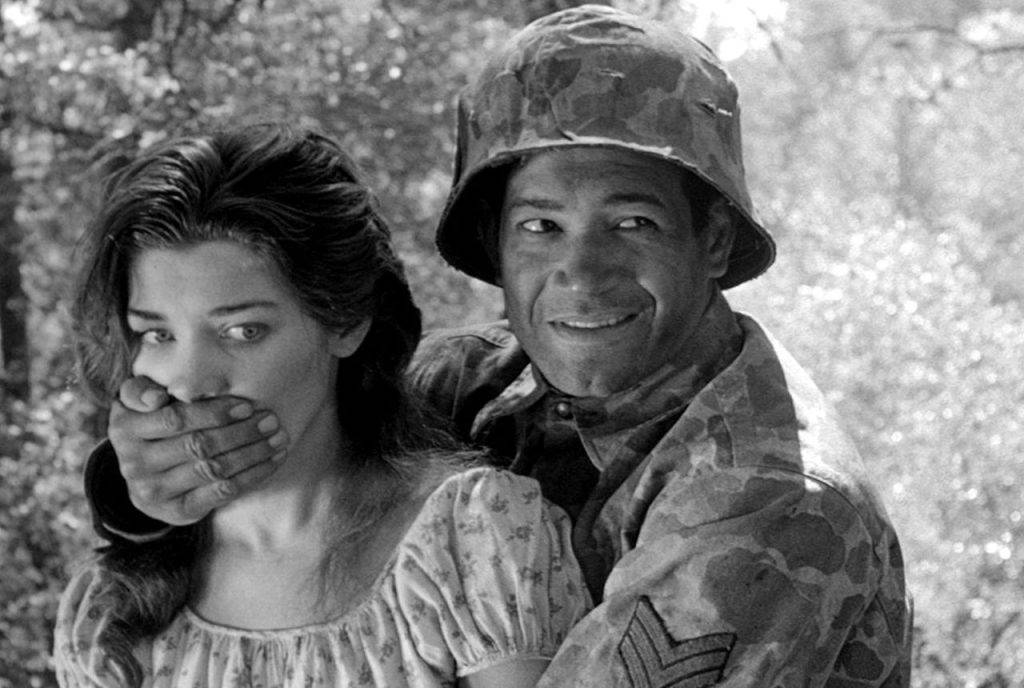

Few Second World War films are as gleefully cynical, morally unclean, and politically uncomfortable as Black Book. Directed by Paul Verhoeven, this Dutch-German-British production dismantles the comforting myths of resistance heroism and liberation justice, replacing them with betrayal, opportunism, and survival at any cost.

It is one of the more honest cinematic portraits of how occupation, intelligence work, and post-war reckoning actually functioned on the ground.

Set in Nazi-occupied Netherlands, the story follows Rachel Stein, a Jewish singer who survives a massacre and is absorbed into the Dutch resistance. Her assignment places her inside the German security apparatus, where loyalties blur, information leaks sideways, and personal survival quickly outranks ideology.

It is counter-intelligence warfare at close quarters: informants, double agents, safe houses compromised by loose tongues, and decisions made in minutes that cost dozens of lives.

Verhoeven returns to Europe after years in Hollywood and brings his full arsenal. He has moral inversion: Nazis can be cultured, polite, even pragmatic; resistance fighters can be venal, brutal, and casually antisemitic. With sex and power, intimacy is not romanticised but weaponised. Bodies are bargaining chips, not symbols. Verhoeven has strict genre discipline: despite its length, the film moves like a thriller, with clear stakes, sharp reversals, and escalating tension.

Carice van Houten delivers a performance that avoids martyrdom. Rachel is neither saint nor symbol. She adapts, hardens, and compromises. In Verhoeven’s world, virtue is not rewarded. Competence is.

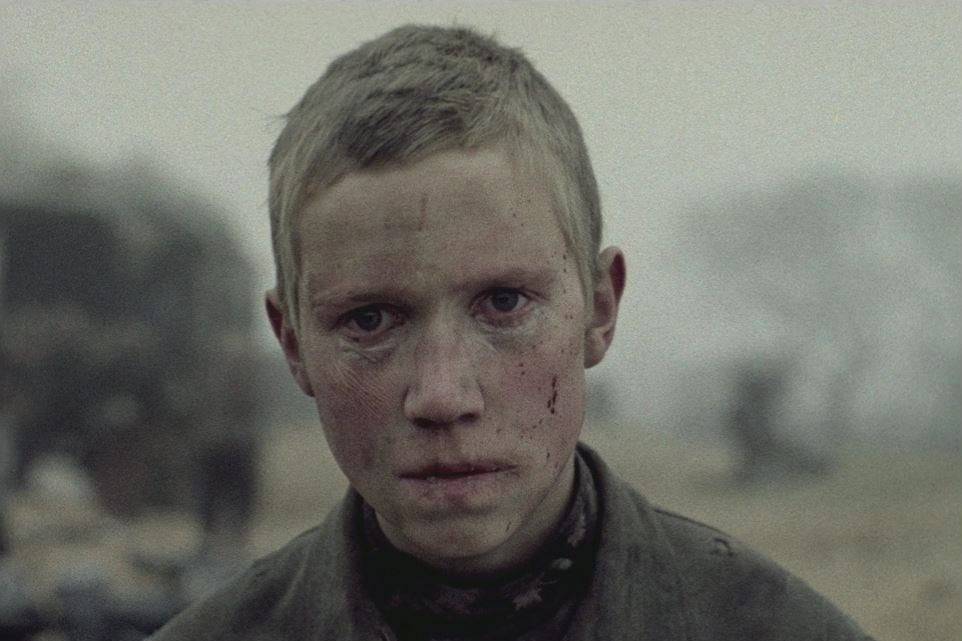

The film balances classical wartime visuals with moments of near-satirical cruelty, especially in its depiction of liberation as something far messier than victory parades suggest.

Black Book excels where many war films fail: it understands how occupation and resistance actually worked. Verhoeven shows penetration of enemy bureaucracies, control of information, tradecraft failures, and how one compromised messenger can collapse an entire network.

The film correctly portrays resistance groups as fragmented, paranoid, and politically divided, closer to intelligence cells than patriotic militias.

The Sicherheitsdienst and Gestapo are shown less as cartoon villains and more as administrators of terror: files, interrogations, internal rivalries, career calculations. This rings historically true, especially in Western Europe, where occupation relied as much on paperwork as on brute force.

The post-liberation sequences are among the film’s most historically accurate and most disturbing. Score-settling, summary punishments, sexual humiliation, and retrospective heroism all appear. Verhoeven punctures the myth that 1945 cleanly separated collaborators from patriots.

The film reminds us that resistance movements were morally compromised and politically divided. The intelligence failures, not battlefield losses, killed most operatives. And liberation often empowered the worst people first. As so often in fiction, some coincidences stretch plausibility. Verhoeven occasionally indulges in shock where restraint might deepen impact. These excesses are part of the point: war, in this telling, is not tidy.

Black Book is not a comforting war film. It is one of the most complete expressions of Paul Verhoeven’s worldview. It is a rare cinematic study of resistance, occupation, and post-war vengeance that aligns more closely with archival reality than patriotic myth.