BAE Systems delivered robust financial results in 2024, reflecting strong defence sector momentum. Annual sales reached £28.3 billion, a ~14% year-on-year increase in constant currency terms. Underlying EBIT climbed to £3.0 billion, up 14% in constant currency, and operating profit was £2.69 billion, up 4% on a reported basis. Order intake in 2024 was £33.7 billion – slightly lower than the prior year’s exceptionally high £37.7 billion – but the order backlog swelled to a record £77.8 billion, indicating decades of future revenue. Indeed, BAE’s order book – funded orders under IFRS – grew to £60.4 billion, underscoring the company’s significant long-term programme visibility. Free cash flow remained strong at £2.5 billion, supporting continued investment and shareholder returns. The dividend per share was raised by 10% to 33.0 pence.

These figures illustrate not just investor confidence but tangible commercial traction in defence. BAE’s diverse portfolio helped it capture rising military spend across domains, mitigating reliance on any single programme. The company ranks as the seventh-largest global defence contractor by revenue, and its broad spread of projects contributed to double-digit growth in 2024 despite supply chain challenges and inflation. Notably, management reaffirmed a positive outlook for 2025, forecasting high-single-digit growth in sales, EBIT and earnings, with guidance unchanged after a “strong start to 2025”. This suggests BAE is capitalising on heightened defence budgets and orders, converting them into real financial performance. For defence decision-makers, the takeaway is that BAE Systems enters 2025 in sound financial health – a solvent, cash-generative partner with the scale to deliver major programmes on schedule. Its improving cash flow and solid balance sheet, even after the £4.4 billion Ball Aerospace acquisition, ensure it can invest in new capabilities and ramp up production where needed.

BAE’s financial trajectory underscores its growing traction in an increasingly busy defence market. While investor-centric metrics are secondary in importance to defence outcomes, they do indicate BAE’s capacity to sustain large projects and innovate. A £77.8 billion backlog, equivalent to about three years’ sales, provides stability and confidence that BAE can undertake long-term development of next-generation systems with less financial risk. This positions the firm as a reliable industrial backbone for the UK and allied defence plans, so long as it maintains execution discipline and supply chain resilience amid high demand.

Core Portfolio and Flagship Programs: Eurofighter Typhoon and Nuclear Submarines

BAE Systems’ portfolio spans all major domains – air, land, sea, cyber and space – making it one of the broadest defence companies globally. Its main products and services include a mix of current flagship programmes and strategically important future systems. The company highlights a number of key franchises driving its business:

- Combat Aircraft: BAE is a prime contractor and integrator for advanced military aircraft. It leads production of the Eurofighter Typhoon for the RAF and export customers, and provides a substantial workshare on the F-35 Lightning II (producing rear fuselage sections and other components). BAE also supports and upgrades these jets and provides military flying training. The Typhoon remains a core platform; in 2024, BAE secured orders for additional Typhoons, including 25 for Spain and up to 24 for Italy, extending the production line and European air combat capability. Through the F-35 programme, BAE benefits from the jet’s global deployment – the company expects F-35 assembly and sustainment work to remain steady or grow as the fleet expands. Looking ahead, BAE is co-leading the development of the Future Combat Air System under the Tempest/Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) – a sixth-generation stealth fighter project with Italy and Japan that is strategically crucial for maintaining air superiority in the 2035+ timeframe. The GCAP partnership will leverage BAE’s aerospace engineering pedigree to create a networked system-of-systems (manned fighters, drones, and new weapons), and BAE’s role safeguards UK industrial capability in combat aviation for decades.

- Maritime – Submarines and Warships: BAE Systems is the UK’s sole builder of nuclear submarines, and this know-how is central to its portfolio. It is manufacturing seven Astute-class attack submarines and designing/building four new Dreadnought-class ballistic missile submarines, which will carry the UK’s nuclear deterrent. BAE is also deeply involved in designing a next-generation nuclear attack submarine under the trilateral AUKUS pact – dubbed SSN-AUKUS – to replace Astute-class boats for both the Royal Navy and Australian Navy. Early design and mobilisation for SSN-AUKUS is underway at BAE’s Barrow shipyard. Recent UK defence announcements underscore the importance of this work: Britain aims to increase its nuclear attack submarine fleet from 7 boats to “as many as 12,” backed by over £6 billion investment in submarine industrial capacity at BAE and Rolls-Royce. This will boost BAE’s production rate and workforce at Barrow, aligning with strategic demands for undersea capability. In surface warships, BAE is building advanced Type 26 frigates (also known as the City-class) – eight for the Royal Navy – and has exported the design to Australia and Canada. In 2024, BAE won a £4.6 billion contract to deliver the first three Hunter-class frigates (a Type 26 derivative) to the Royal Australian Navy, with construction now underway in Osborne, South Australia. BAE also provides the reference design for Canada’s Surface Combatant program (CSC). These complex warship projects are flagship naval programmes for allied nations, making BAE a key enabler of allied naval interoperability. Additionally, BAE performs naval ship repair and sustainment in both the US and UK, supporting vessels for the Royal Navy, US Navy and Australian Navy – an important services business that complements new shipbuilding.

- Land Systems and Armoured Vehicles: BAE’s land portfolio includes armoured fighting vehicles, artillery, and munitions. Its BAE Hägglunds subsidiary in Sweden produces the CV90 infantry fighting vehicle, a proven platform now in service or on order with multiple European armies. Notably, in 2024, BAE won orders worth ~$2.5 billion to supply upgraded CV9035 MkIIIC vehicles to Sweden and Denmark – a significant boost driven by NATO countries rearming. BAE also makes the BvS10 all-terrain vehicle and ARCHER 155mm artillery system for international customers. In the US, BAE Systems, Inc. manufactures combat vehicles such as the Bradley IFV family and the new Armoured Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) for the US Army, as well as the Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV) for the US Marine Corps. These programs keep their US production lines busy and underscore transatlantic breadth. On the munitions side, BAE is a major supplier of ordnance – from small arms ammunition up to artillery shells and warheads – especially for the UK and US. The war in Ukraine has sharply increased demand for artillery rounds, and BAE is investing heavily to expand capacity. The company is opening a new artillery shell factory in Yorkshire and expanding other UK munitions sites to achieve a sixteen-fold increase in 155mm shell output. It is also developing Next Generation Adaptable Ammunition (NGAA) to enable faster, more flexible production of artillery rounds. This responsiveness to munition stockpile needs has strategic importance as NATO focuses on strengthening its war reserves. Additionally, through its 37.5% ownership of MBDA (Europe’s leading missile-maker), BAE participates in a broad portfolio of missile systems (from air-to-air missiles to anti-ship and SAMs). MBDA secured significant orders in 2024 – for example, Poland’s NAREW air defence system and additional Aster and Patriot missiles for European defence – which bolster BAE’s indirect revenues and influence in the precision weapons domain.

- Electronic Systems and Cyber: BAE’s Electronic Systems division, largely US-based, produces a wide range of high-tech subsystems critical to modern warfare. These include Electronic Warfare (EW) suites for aircraft, such as the state-of-the-art jamming and countermeasure systems on fighters and bombers. BAE is also a leader in precision-guided munitions sensors, avionics and flight controls, for both military and civil aircraft, C4ISR systems, and electric drive propulsion for ground vehicles. In 2024, BAE dramatically expanded its space and electronics capabilities by acquiring Ball Aerospace, a US company now renamed BAE Space & Mission Systems. This $5.5 billion acquisition, completed in February 2024, adds world-class expertise in satellites, space payloads, and optical instruments. Ball’s business has deep customer ties with the US Intelligence Community, NASA, and the Pentagon, and is well positioned in growth markets like missile defence sensors and spacecraft. We see immediate payoffs: in June 2025, BAE won a $1.2 billion US Space Force contract to build a new medium Earth orbit missile-warning satellite constellation, 10 satellites plus ground systems – a direct result of adding Ball’s space technology to BAE’s portfolio. This contract underscores BAE’s arrival as a prime contractor in the space domain, delivering resilient satellite networks for strategic missions. In parallel, BAE’s Digital Intelligence and cyber security arm provides classified intelligence analysis, cyber operations support, and secure IT systems for governments – primarily the UK, US, and allies. It delivers services like network defence, threat intelligence, and even synthetic training environments for militaries. BAE is leveraging emerging tech here, using Artificial Intelligence to enhance its offerings – for example, experimenting with Large Language Models to assist maintenance crews by instantly querying vast technical manuals, and using digital twins to speed up software deployment in critical national infrastructure. These digital innovations improve efficiency and keep BAE’s services at the cutting edge of cyber warfare and secure communications.

- Advanced and Uncrewed Systems: Anticipating the future, BAE has ramped up efforts in autonomous systems, drones, and next-gen technologies. Its new FalconWorks unit, an internal skunkworks, is focused on disruptive innovation, including uncrewed aerial systems (UAS). In 2024, BAE acquired UK drone manufacturers Malloy Aeronautics, a specialist in heavy-lift quadcopters, and Callen-Lenz, which develops UAV avionics and control systems. These additions strengthen BAE’s position in both rotary and fixed-wing UAS, complementing ongoing work on combat drones. BAE is already known for projects like the Taranis UCAV demonstrator and loyal wingman concepts, and the company’s portfolio now spans from small tactical drones up to large autonomous combat aircraft in development. It also recently acquired Kirintec, a company expert in counter-drone and electronic countermeasures, to boost its capabilities in defeating enemy drones and improvised threats. This holistic approach – building drones and the systems to counter them – aligns with lessons from Ukraine, where uncrewed systems and anti-drone tech have become indispensable. Beyond drones, BAE’s innovation includes autonomous undersea vehicles, e.g. the Herne unmanned submersible, and proof-of-concept combat vehicles like the Atlas demonstrator, which uses open architectures for rapid upgrades. All these efforts in autonomy, AI, and robotics are strategically aimed at future-proofing BAE’s product lineup for the next era of warfare.

BAE Systems’ core portfolio covers the full spectrum of defence needs – from fighter jets and submarines to cyber defence and space assets. Its flagship programmes (Typhoon, Dreadnought, Type 26, CV90, etc.) ensure it remains deeply embedded in the force structure of the UK and key allies. Meanwhile, its investment in emerging domains (drones, AI, space) and big collaborations (like GCAP and AUKUS) positions BAE to shape the future battlefield. This breadth gives BAE resilience and strategic relevance: it can offer militaries integrated solutions across domains, which is increasingly important as concepts like multi-domain operations and joint all-domain command and control take hold.

Global Customers and Geopolitical Footprint

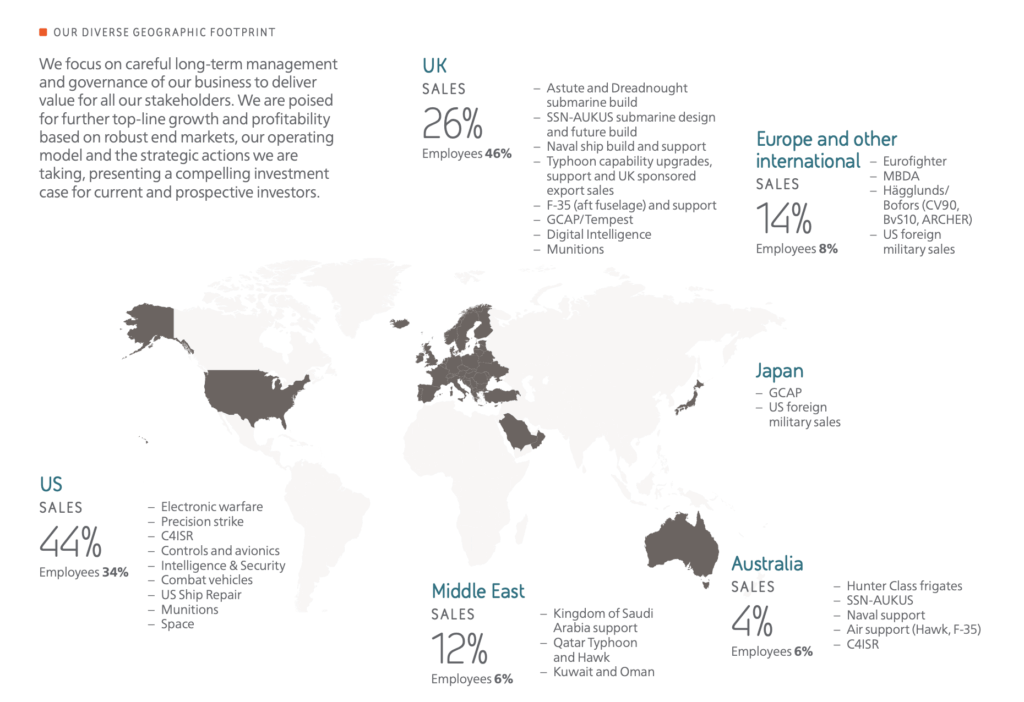

As a British-based company with global reach, BAE Systems serves a wide array of nations – and each partnership carries geopolitical significance. The company’s principal markets are the United Kingdom, United States, Saudi Arabia, and Australia, with strong positions across Europe and growing links in the Asia-Pacific. BAE’s geographic footprint is unique: over 107,000 employees operate in more than 40 countries. Sales are well diversified by destination: the US accounted for 44% of 2024 sales, the UK 26%, Saudi Arabia 10%, Australia 4%, and other international markets 16%. This spread reflects BAE’s role as a transatlantic defence integrator and a key supplier to allied governments worldwide.

United Kingdom: As Britain’s leading defence contractor, BAE is intimately tied to UK defence capability and policy. It provides critical equipment to Her Majesty’s Armed Forces – from the Royal Navy’s ships and submarines to the RAF’s combat aircraft and the British Army’s munitions. Major UK programmes like Dreadnought, Tempest, Type 26 frigates, and the Future Soldier modernization all involve BAE. The UK Ministry of Defence relies on BAE not only to equip the forces but also to sustain industrial skills and sovereignty. In turn, the UK remains BAE’s second-largest market, over a quarter of sales, and ongoing projects like the new submarines and GCAP fighter ensure that the MoD will invest heavily in BAE for years to come. The relationship also has a strategic industrial angle: BAE and the UK government collaborate to export British-designed defence equipment abroad, which strengthens alliances and brings economies of scale. For instance, UK-sponsored Typhoon exports (to Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, etc.) and joint development of systems like MBDA missiles are explicitly part of Britain’s defence industrial strategy. BAE’s prominence in the UK’s supply chain also means that British defence strategy – such as the 2025 Strategic Defence Review – directly shapes BAE’s priorities, explored more in the next section.

United States: BAE’s American subsidiary (BAE Systems, Inc.) makes it a de facto US defence contractor, insulated under a Special Security Agreement. The US is BAE’s largest single-country market, comprising 44% of sales, and BAE is a top-10 Pentagon supplier by volume. The firm has a strong standing in the US armoured vehicles sector (e.g. Bradley/AMPV programmes), electronic warfare, supplying systems for U.S. fighters and naval platforms, and services, ship maintenance and modernization at U.S. naval yards. BAE’s foothold in the massive US defence budget yields not just revenue but technological benefits – many of its innovations in autonomy, space, and C4ISR stem from US-funded projects or acquisitions like Ball Aerospace. Strategically, BAE’s transatlantic presence supports US-UK interoperability and ensures that British industry partakes in cutting-edge US programs. For example, BAE is a partner on the F-35 program, giving the UK a stake in the world’s largest fighter project. The US business is also pivotal for BAE’s future growth: as the US increases spending on priorities like missile defence, space resilience, and next-gen combat vehicles, BAE is well-positioned to win contracts, as evidenced by the recent Space Force award. This deep integration with the US defence ecosystem aligns with broader AUKUS and NATO cooperation goals.

Middle East – Saudi Arabia and Gulf States: BAE has a long-standing, if sometimes controversial, relationship with Saudi Arabia, which remains one of its biggest export customers. Through the Salam programme and others, BAE supplied the Royal Saudi Air Force with Typhoon fighters and Hawk trainers, and it provides ongoing support, training, and upgrades in the Kingdom. Saudi-related work (including support contracts) constituted about 10% of BAE’s sales in 2024 – a substantial share. These contracts are geopolitically significant: they tie the UK closely to Gulf security and have been subject to political scrutiny (e.g. regarding use in Yemen). Nonetheless, the Saudi-UK defence partnership underpins Saudi Arabia’s military modernization and advances the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 industrial goals (BAE has helped establish local capability and licensed production, aligning with Saudi Arabia’s desire for self-sufficiency). Beyond Saudi Arabia, BAE also supports air forces in Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman, who have bought Typhoons or other BAE systems. For example, Qatar recently received Typhoon and Hawk deliveries, and Oman operates Eurofighter and other BAE-supplied kit. BAE’s presence in the Middle East thus reinforces Western-aligned Gulf defence capacity. In a geopolitical context, this network of Gulf partnerships contributes to containing regional threats and securing energy infrastructure. It also reflects a careful balance – the UK government must manage these defence exports in line with foreign policy and humanitarian considerations, an area where BAE often finds itself at the nexus of commerce and diplomacy.

Europe and NATO Allies: Across Europe, BAE Systems is benefiting from the largest rearmament drive in a generation. Numerous European NATO members have announced major increases in defence budgets in response to Russian aggression. BAE, with its broad European footprint (Sweden, UK, etc.), is positioned to supply much of the advanced kit these countries seek as they replace ageing Soviet-era or early Cold War equipment. For instance, in Northern and Eastern Europe, BAE’s Bofors and Hägglunds businesses have seen surging demand for artillery and armoured vehicles – exemplified by Sweden and Denmark’s large CV90 orders in 2024. Finland and Norway have also fielded BAE’s vehicles (CV90 and BvS10), and more upgrades are likely. BAE’s share in MBDA means it also profits from European collaborative missile projects; MBDA’s recent orders for CAMM, Aster, and other missiles to Poland, Italy, Germany (via Sky Shield) and others highlight how European nations are turning to consortium-built missile defences. In the air domain, apart from Eurofighter sales, BAE’s role in GCAP links it with Italy and Japan, and it continues to support Eurofighter Typhoons operated by Germany, Spain, Italy and others – upgrades and support contracts are ongoing, and BAE’s Samlesbury site builds Typhoon rear fuselages for all partner nations. Additionally, through US Foreign Military Sales (FMS) channels, BAE’s US subsidiaries sell to European allies – e.g. BAE-built howitzers or combat vehicles supplied to countries like Romania or the Czech Republic via FMS. The net effect is that BAE plays a central role in arming Europe’s front-line states with modern Western equipment, bolstering NATO’s eastern flank. This carries geopolitical weight: by deepening defence industrial links across Europe, BAE indirectly strengthens the European pillar of NATO and ensures interoperability – for example, a BAE CV90 operated by a Nordic country can work seamlessly with British Army units in joint deployments. It’s worth noting that BAE also maintains a strategic partnership with Türkiye on certain projects, and had past joint ventures in land systems, although the focus now is more on Western Europe given geopolitical alignments.

Asia-Pacific: BAE’s presence in Asia-Pacific is anchored by Australia, where it is the largest defence contractor. Australia’s military build-up – including the AUKUS submarine programme and massive investments in naval ships and vehicles – flows directly through BAE. The company’s Australian arm is building the Hunter-class frigates in Adelaide and will be intimately involved in delivering nuclear submarines under AUKUS (both Pillar 1, the new sub design, and Pillar 2, other advanced capabilities). BAE Australia also provides ship support and integration (e.g. for the new Arafura-class patrol vessels and Hobart destroyers), and has built armoured vehicles like the Land 400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles in partnership. The geopolitical meaning is significant: Australia sees BAE as a bridge to UK and US technology, reinforcing the Three Nations’ cooperation against potential Indo-Pacific threats. Beyond Australia, BAE is active in markets like Japan, where its inclusion in GCAP marks a historic UK-Japan industrial collaboration on par with the US-Japan alliance. Japan’s choice to partner with BAE on a fighter signals a broader geopolitical shift – integrating UK defence tech into East Asia’s security network. BAE is also exploring opportunities in countries such as India (where it has supplied Hawk trainers and naval guns in the past), South Korea (which is both a competitor and partner in some areas), and smaller Southeast Asian states upgrading their naval fleets or artillery. Notably, BAE’s Naval Gun Systems (like the Mk45 naval gun) and air defence missiles via MBDA have found customers in places like the Philippines and Singapore, while its cyber division offers services to allies across Asia. Each such deal – however small – strengthens Western-aligned capabilities in a region where China’s rise is the central strategic concern.

BAE Systems’ global customer base is not just a commercial footprint but a map of UK and allied strategic influence. Wherever BAE sells a fighter, frigate, or howitzer, it forges long-term relationships – training, maintenance, supply of upgrades – that bind those armed forces closer to the UK/US sphere of interoperability. For defence and military decision-makers, BAE’s role in multiple national arsenals means it can act as a conduit for coalition operations. However, it also means BAE is exposed to geopolitical risk: shifting alliances, export controls, or diplomatic disputes can directly impact its business – for example, a future downturn in UK-Saudi relations could affect support contracts. So far, the trend is positive for BAE – global instability has prompted nations to rearm, and BAE’s alignment with NATO and key partner nations’ needs has translated into record orders. The company appears to be managing the geopolitical balancing act by focusing on trusted partners and high-integrity export deals approved by its home governments.

Future Growth Areas and Innovation: Air, Undersea, Digital and Space Warfare

Looking ahead, BAE Systems is positioning itself for the next generation of defence technology and growth markets. Several key areas stand out as focus points for future growth, each with significant investment and strategic value:

- Next-Generation Combat Systems: BAE’s involvement in flagship future programmes like GCAP/Tempest and SSN-AUKUS ensures it will be at the forefront of 6th-generation air combat and advanced undersea warfare. These development programmes are not immediate revenue spinners, but they are crucial for long-term growth and relevance. The Global Combat Air Programme aims to field a new fighter in the late 2030s, and BAE’s role as lead integrator secures decades of work in design, production, and through-life support. Similarly, designing the AUKUS submarine will likely lead to the construction of potentially dozens of boats for the UK and Australia over many years. These are mega-projects measured in tens of billions of pounds, and success would cement BAE’s technological leadership (as well as national security independence for its home markets). BAE is also developing uncrewed combat aircraft to accompany manned fighters – such as loyal wingman drones under the UK’s “Mosquito” program, now part of FalconWorks – which could be a significant new product line by the late 2020s. On land, while BAE’s UK vehicle division is now partly in a JV (RBSL) with Rheinmetall, BAE is active in the future artillery and combat vehicle space through its US business and Hägglunds. The US Army’s competition for a next-gen Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) and other future vehicles presents opportunities if BAE can leverage its Bradley/AMPV experience to win or partner. In Europe, concepts for the Main Ground Combat System(MGCS) or future tank could involve BAE via its Swedish arm (if British involvement is sought alongside France/Germany). In essence, BAE is aligning itself to not miss the boat on any next-gen platform, be it in the air, sea, or land domain.

- Digital Capabilities and AI Integration: BAE’s future growth also hinges on mastering digital transformation in defence. This means using artificial intelligence, big data, and software innovation to add value to traditional hardware. BAE is investing in digital engineering – for example, employing digital twins and advanced simulation to reduce development cycles. The 2024 Annual Report highlighted how faster product development was achieved by re-using software components and open architecture approaches, the Atlas armoured vehicle and Herne UUV were cited as prototypes built in under a year. By adopting modern agile development methods, BAE aims to deliver new technology to customers at “wartime pace” – a critical demand from governments observing the rapid innovation in Ukraine. AI is a big part of this: BAE is already using AI internally, e.g. LLMs for maintenance knowledge management, and is likely integrating AI/ML into its products – for instance, autonomous navigation algorithms in drones, predictive maintenance in fighter aircraft, and decision-support systems in command and control. As militaries seek to harness AI for faster OODA loops, BAE’s expertise in both software and mission knowledge positions it to offer AI-enabled solutions that are trusted, leveraging its decades of defence domain experience. The new UK defence strategy explicitly calls for a step-change to get technology “into the hands of armed forces quickest”, which implies more digital and AI-driven procurement. BAE’s challenge and opportunity is to pivot from a hardware-centric model to becoming equally a defence software and data company – a transition it appears to be embracing through its Digital Intelligence segment and partnerships with tech firms.

- Space and High-Tech Domains: With the acquisition of Ball Aerospace, BAE signalled that space is a major growth frontier. Governments are investing heavily in space-based surveillance, secure communications, and PNT (positioning, navigation, timing) due to threats to satellites and the need for resilient networks. BAE’s new Space & Mission Systems division can now bid as a prime contractor on large US and UK space programmes. The $1.2 billion US missile-tracking satellites contract is likely the first of many. The UK’s own military space ambitions, e.g. ISTARI satellite constellation for ISR, or participation in multi-nation satellite projects, could involve BAE as a domestic lead. In addition, BAE’s advanced electronics portfolio – semiconductors for RF, sensors, quantum technologies, etc. – will feed growth as nations pour R&D into tech superiority. Notably, BAE has been working on technologies like directed energy weapons, hypersonics (through seekers and control systems, possibly via MBDA), and next-gen radar (e.g. its role in the UK’s ECRS Mk2 radar for Typhoon). These are areas where future funding is headed. The UK’s 2025 defence review stresses investing in “drones, cyber and other critical new technologies” alongside conventional kit. BAE is aligning to that vision: it recently opened a dedicated Future Technologies centre and has been ramping up internal R&D – self-funded R&D spend increased, and FalconWorks is pursuing outside venture investments. Moreover, international collaborations are a growth avenue in themselves: partnering with allies on cutting-edge tech means shared costs and access to broader markets. BAE’s involvement in AUKUS Pillar 2 projects – which include cyber, AI, underwater drones, and long-range strike – could yield new products that it can sell to other allies too. Its decades-long participation in international consortia (Tornado, Eurofighter, F-35, MBDA) show that BAE can be a team player in global projects, which will be key for things like a NATO Future Surveillance system or European Strategic Airlift improvements.

- Sustainment, Upgrades and Training: While new platforms grab headlines, a significant growth and profit area for BAE is through-life support and upgrades of existing systems. As allied militaries expand their fleets, every new sale begets 30+ years of support services. BAE’s outlook includes expanding its maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) offerings and training solutions. For example, BAE provides the RAF’s pilot training, through the Military Flying Training System, and could offer similar services abroad. The shift to digital training – simulators, VR, AI-driven scenarios – is another niche BAE can grow, especially as forces aim to save money and wear on equipment by doing more in simulators. Upgrades, mid-life extensions and digital retrofits are almost inevitable given budget constraints – BAE is already performing capability upgrades on Typhoon – e.g. integrating new missiles and electronic systems – for the partner nations, and one can foresee similar roles for BAE on the F-35, where it is vying to be a key global maintenance hub. In land, the British Army’s Challenger 3 tank upgrade is being done by RBSL (the JV including BAE), but BAE proper could play a role in upgrading US Army vehicles or overseas fleets it’s sold to, e.g. CV90 users upgrading sensors or adding active protection systems – something BAE can supply. All these sustainment activities both provide steady revenue and keep BAE close to the customer, positioning it well for when those customers move to the next generation.

In evaluating these areas, it’s clear BAE’s growth strategy is two-pronged: first, capture the immediate upswing in demand (more orders for existing products like CV90s, Typhoons, ammo, etc., as countries re-arm quickly), and second, invest in the innovation that will meet future requirements in the 2030s – stealth, autonomy, AI, space. The risk is that the company must execute on current orders, producing on time despite supply chain strains, while not underinvesting in R&D. However, BAE appears to be managing this balance – 2024 saw it both deliver strong results and spend £1 billion on expanding facilities and tech, such as a new shipbuilding hall and artillery shell lines in the UK. The “demand signal” from governments is encouraging BAE to boost capacity and efficiency now, which should pay off in both near-term output and long-term capability – for instance, automating manufacturing processes will help with both current shell orders and future production of more complex systems. International collaboration also means cost-sharing – GCAP funding is split three ways, AUKUS development will be shared with Australia and the US – reducing BAE’s financial burden and ensuring a ready market for the end product.

BAE’s future growth areas are tightly aligned with the direction of allied defence spending: more high-tech systems, more digital integration, and stronger international industrial ties. If it continues on this path, BAE will likely remain one of the world’s defence powerhouses, equally adept at providing today’s hardware and tomorrow’s intelligent, networked solutions.

Alignment with Britain’s 2025 Defence Strategy

The UK’s new defence strategy – encapsulated in the Strategic Defence Review (SDR) 2025: “Making Britain Safer” published in June 2025 – provides important context for BAE Systems. The review calls for a “new era for UK Defence” with a focus on warfighting readiness, cutting-edge technology, and stronger industry partnerships. As Britain’s premier defence contractor, BAE’s plans and products are highly interwoven with these national objectives.

One of the headline commitments of the SDR is the largest sustained increase in UK defence spending since the Cold War, rising to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, with an ambition for 3% later. This growth in funding is targeted not at expanding troop numbers, but at expanding capabilities – particularly drones, digital warfare, and nuclear deterrence, as stated by PM Sir Keir Starmer and Defence Secretary John Healey. BAE stands to be the prime beneficiary and enabler of this shift. For instance, the review emphasises investment in uncrewed systems and data-centric warfare over a larger conventional army. BAE’s portfolio – from combat drones,via FalconWorks, to its Digital Intelligence cyber unit – directly aligns with this, meaning BAE will likely receive R&D contracts and production orders in these areas as the MoD pivots to software, AI, and automation. Indeed, the SDR explicitly notes the transformational impact of drones in Ukraine and calls for rapid fielding of new tech to the armed forces. BAE’s ongoing work on combat UAVs and integration of AI into defence systems is in lockstep with that vision.

Crucially, the SDR also underscores a new “partnership with industry” and the concept of a “defence dividend” for the economy. The government wants to strengthen supply chain resilience, invest in the UK industrial base, and leverage defence spending to create jobs and growth nationwide. BAE is at the heart of this initiative – its presence in shipyards (Glasgow, Barrow), factories (munition plants in the North), and aerospace hubs – Warton, Samlesbury – means BAE is both a recipient of government investment and a vehicle to deliver economic benefits. BAE’s CEO welcomed the review as a “clear demand signal” for the industry to invest in capacity and new technologies. The company has, in fact, anticipated this: in the last year it invested £1 billion in UK facilities, building new infrastructure like the frigate production hall on the Clyde and the expanded artillery shell facilities in the North of England. These moves align perfectly with the government’s call to boost domestic production capacity so that the UK can both re-arm and export. The SDR’s emphasis on resilience and self-reliance, a lesson from recent supply chain disruptions and the war in Europe, plays to BAE’s strength as a domestic producer of critical capabilities – be it nuclear submarines, radar electronics, or ammunition. We have already seen concrete steps: days after the SDR, the UK Treasury announced £6 billion for the submarine construction infrastructure at Barrow and for Rolls-Royce’s nuclear plant, ensuring the AUKUS and Dreadnought programs can scale up. This is a direct follow-through on the strategy, effectively funnelling resources into BAE’s domain to guarantee the UK can meet the goal of 12 new submarines.

Another pillar of the strategy is international cooperation – NATO-first, but also partnerships like AUKUS and GCAP that extend beyond NATO. BAE’s alignment here is evident: it is a core partner in AUKUS and the lynchpin industrial partner for GCAP, and also works within MBDA for Franco-British missile projects. The SDR specifically praises strategic international programmes such as AUKUS and GCAP for fostering innovation and strengthening alliances. BAE’s role in these means the company is essentially executing the UK strategy on the industrial front. The review also puts “NATO first” but “not NATO only”, meaning the UK will lead in Europe but also pursue bilateral deals. BAE is facilitating this by, for example, the Trinity House agreement with Germany (a recent UK-Germany pact mentioned in the SDR) likely involving industry collaboration – BAE’s 37.5% stake in MBDA alongside Airbus (a German/French stakeholder) is an illustration of how UK industry (via BAE) is interwoven with European defence industry. The House of Lords summary of the SDR noted that the UK and allies must step up on European security, and indeed, BAE’s exports of munitions and vehicles to Eastern Europe are a direct support to that collective security aim.

From BAE’s perspective, the new UK strategy provides a favourable tailwind: it virtually guarantees sustained or increasing home market orders across all domains. Where earlier reviews a decade ago were about cuts and austerity, the 2025 SDR is about expansion and modernisation – music to industry’s ears. The company will, however, be held to account on delivering value: alongside spending more, the MoD is keen on procurement reform and results. The SDR talks about “radical reform of procurement” and making the UK a “leading edge of innovation in NATO”. This implies that BAE will be expected to deliver complex projects on time and on budget, and to innovate faster. The government’s trust (and cash) comes with pressure – evidenced by the Defence Secretary’s comment that old ways of doing business must change and whoever adopts new tech fastest will win. BAE’s management recognises this; CEO Dr. Charles Woodburn noted the need to “boost capacity, drive efficiencies and shape our portfolio to support future growth” in light of the evolving landscape. The company is actively engaged with the MoD on the ongoing Defence Industrial Strategy refresh and the SDR implementation, signalling BAE’s intent to remain the partner of choice by being responsive and innovative.

Alignment is visible in areas like: expanding UK stockpiles, BAE upping ammo production, nuclear deterrent renewal (BAE building Dreadnought subs and designing new warhead support systems, likely in tandem with AWE), resilient comms, BAE’s involvement in cyber and space should grow as UK invests in secure SATCOM and networks, and warfighting readiness. The Army’s focus on warfighting division-level capability means programmes like Challenger 3, new Apache helicopters, and perhaps more MLRS – many of which involve BAE inputs for munitions, avionics, etc.. The review also highlights a commitment to 5% of GDP on security by 2030, including 3.5% core defence, which suggests a steady increase in procurement budgets. BAE, as the dominant local player, will naturally absorb a good portion of that in contracts.

It’s worth mentioning the SDR’s focus on skills and jobs – BAE’s growth aligns here too. The company has added ~15,000 UK employees in the past five years and runs extensive apprenticeship and graduate schemes. The government’s narrative of defence as a growth sector and source of high-value jobs dovetails with BAE’s investments in training and hiring. BAE spent £230 million on education and skills in 2024. This mutual interest ensures government support for BAE’s workforce expansion, such as through local content requirements or training grants for big projects.

In summary, BAE Systems is highly aligned with Britain’s new defence strategy – almost to the point of being its industrial embodiment. The 2025 review stresses exactly the areas BAE is strongest in, advanced conventional kit plus new tech, and provides funding and policy support for BAE to thrive. BAE has publicly welcomed the strategy, noting it “rightly balances conventional equipment like combat aircraft, submarines and ships with drones, cyber and other critical new technologies”. The company also highlighted the SDR’s emphasis on supply chain resilience and international alliances, affirming that this “gives our sector the confidence to invest… in cutting-edge technologies to meet evolving requirements for the UK and our allies”. Going forward, one can expect BAE to play a central role in delivering the UK’s defence ambitions – whether it’s increasing the mass of the Royal Navy, fielding swarms of drones for the British Army, or ensuring the RAF has world-class combat air and training. For the MoD and allied military planners, BAE’s alignment means they have a willing and capable industry partner to implement the strategy. For BAE, the strategy effectively charts a growth roadmap with government backing. The onus will be on execution: delivering the promised capabilities at pace. If BAE can do that, it will reinforce the wisdom of the government’s bet on domestic industry as a cornerstone of national security.

Read More:

- BAE Systems: Annual Report 2024

- Reuters: UK to spend more than $8 billion on submarine-building capacity

- Reuters: Britain unveils radical defence overhaul to meet new threats

- Gov.UK: The Strategic Defence Review 2025 – Making Britain Safer: secure at home, strong abroad

- SatNews: BAE Systems’ $1.2 billion contract for U.S. Space Force missile warning and tracking satellite system

- Wikipedia: Royal Saudi Air Force