The Baltic Sea has quietly become a submarine battleground. Sweden’s recent entry into NATO and Poland’s Orka programme are shaking up undersea balances. In November 2025, Warsaw chose Sweden’s Saab to supply three A26 Blekinge-class submarines, a deal worth about 10 billion zloty, 2.4 billion euros.

Poland’s sole existing diesel-electric sub is an ageing Soviet-built Kilo (ORP Orzeł, commissioned 1986), and the A26 purchase will finally replace it. The deal includes deep industrial cooperation – Sweden will buy Polish weapons and even provide a “gap-filler” training sub – and aims to have a contract signed by the end of 2026 so the first new boat arrives by around 2030. Polish officials hail this as a landmark for Baltic deterrence.

- Three A26 submarines for Poland’s navy, optimised for Baltic littoral conditions.

- Industrial package: Sweden will invest in Polish defence firms and send a training sub to bridge the capability gap.

- Schedule: Negotiations run through 2026, with the first A26 expected circa 2030.

The thrust of Poland’s choice is clear: it is buying Swedish subs, not vice versa, because Saab has decades of experience building ultra-quiet AIP boats for shallow, cluttered waters. The A26 (Blekinge-class) is diesel-electric with Stirling AIP engines. This lets it remain submerged for weeks at low speed without snorkelling, cutting noise and radar signature. It carries standard heavyweight torpedoes and mines and features a distinctive “multi-mission portal” in the bow – essentially a 1.5 m lock/launch tube. This allows divers or unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) to deploy, enabling reconnaissance or attacks on undersea targets. In short, the A26 is built to do more than sink ships: it can plant mines, conduct special operations missions, and focus on the seabed. The A26’s multi-mission portal makes it perfect for Baltic littorals and protecting cables and pipelines. The export design even allows an optional vertical-launch section for cruise missiles, if Poland ever opts in.

Five Navies Operate Submarines in the Baltic Sea

Today, only a few navies operate submarines in or around the Baltic: Sweden, Poland, Germany and Russia. The Swedish Navy fields four AIP boats – three modernised Gotland-class and one Södermanland-class – all optimised for Baltic stealth. Gotland-class famously “sank” a US carrier in a 2005 exercise, demonstrating the quietness Saab can achieve. Sweden is also building two new A26 Blekinge-class subs (HMS Blekinge and Skåne), though delivery has slipped to the early 2030s. These subs feature Stirling AIP, multi-mission portals (for divers/UUVs) and advanced sonars.

Poland’s submarine arm is much smaller. Until now, it has had one operational boat, ORP Orzeł, an old Russian Kilo-class submarine. After a decade-long refit, Orzeł finally returned to service in 2024, but it remains the only Polish sub. Once the A26s arrive, from ~2030, Poland will leapfrog to one of NATO’s most modern non-nuclear fleets.

Germany contributes via its Type 212A class. Six of these AIP subs are homeported in Eckernförde on Kiel Bay, giving quick access to the Baltic and North Seas. The Type 212s are widely regarded as among the quietest subs in the world – “nothing beats them” in stealth, according to analysts. In late 2024, Germany even moved to buy four more advanced Type 212CD boats to bolster the northern flank. Those will further tip regional strength toward NATO.

The Russian Baltic Fleet still operates a small submarine force. Its main base is in Kaliningrad (Baltiysk) – one of only two Russian naval bases on the Baltic – with another at Kronstadt near St Petersburg. Active units include a few Kilo-class diesel-electric boats and, recently, the troubled Lada-class Kronstadt, tested in the Baltic. In any given deployment, Russia usually has only two or three Kilos rotating in the area. Russian officials claim they build roughly one new Kilo per year in St Petersburg and Kaliningrad. Even so, their presence is backed by Kaliningrad’s coastal missiles and the shadowy “shadow fleet” of oil tankers. As one Swede put it, Moscow is “continuously reinforcing” its Baltic capabilities.

The other Baltic littoral countries currently have no subs. Denmark retired its subs in 2004 and is only now debating replacements. Finland has been forbidden from owning subs since WWII. The Baltic states rely on patrol craft and minesweepers, not submarines.

Sea Denial, Control and Surveillance

Contrary to romantic images of charging torpedoes, modern Baltic subs have four main peacetime and wartime roles:

- Sea denial and control. In war, NATO’s Swedish, Polish and German boats would try to make large swaths of the Baltic impassable for Russian ships – while also guarding Nato supply lanes. The aim is to blockade Kaliningrad and St. Petersburg from the sea or keep the channels open to defend allies. As NATO’s undersea commander put it, Baltic allies bring “impressive ASW (anti-submarine warfare) capability”, and together they work “to safeguard sea lines of communication [and] protect critical infrastructure”.

- Intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR). Submarines quietly lie on the seabed or inch around at periscope depth, listening for targets. The Baltic is a crowded acoustic maze, so AIP subs use a bank of flank sonars and towed arrays to eavesdrop on Russian fleet movements, test firings and even merchant traffic. These listening missions can trail warships or the “shadow fleet” of tankers, helping spot sanctions evasion or hostile naval build-ups. In short, subs double as underwater spies – a role NATO emphasises in its exercises.

- Seabed and infrastructure warfare. The Baltic is criss-crossed by pipelines and data cables. Recent sabotage episodes have made this a priority. Modern subs like the A26 can carry divers, mines or UUVs through their mission lock. In wartime, they could disable or booby-trap undersea cables and pipelines. Conversely, in peace, they can also inspect and protect cables. NATO even set up a “Baltic Sentry” task force in 2025 after a string of Nord Stream-style attacks on Baltic infrastructure.

- Training roles. Quiet AIP subs also serve as high-value “enemies” for anti-sub training. NATO regularly practices hunting Sweden’s Gotland and Germany’s Type 212, which are notoriously hard to find.

From Karlskrona to Kaliningrad

The main submarine hubs in the region are well known, even if details are secret:

- Karlskrona, Sweden. This historic naval base in Blekinge hosts the Royal Swedish Navy’s 1st Submarine Flotilla. All three Gotland-class and the Södermanland boat operate from here. Saab Kockums also builds the A26s in Karlskrona. The Stockholm archipelago (Muskö) complex nearby provides support and training areas.

- Gdynia, Poland. The Polish Navy’s only sub, ORP Orzeł, is homeported at Gdynia under the 3rd Flotilla. Poland’s new A26s will also be based here, though early training may happen in Sweden. Gdynia has been Poland’s naval hub for decades and will house the expanded fleet.

- Eckernförde, Germany. On Kiel Bay’s southwest corner lies Eckernförde. All six German Type 212A subs are based here (1st Submarine Squadron), along with their tenders and ASW support ships. Eckernförde offers direct access to the Baltic and North Sea; German subs routinely deploy eastward from there.

- Kaliningrad (Baltiysk) and Kronstadt (Russia). The Russian Baltic Fleet’s main bases are at Baltiysk in Kaliningrad and Kronstadt in the Gulf of Finland (outside St. Petersburg). Baltiysk is ice-free year-round and one of only two Russian Baltic ports with subs. Kronstadt supports Baltic units rotating through. Russian Kilo and Lada boats operate out of these bases or nearby training ranges.

Beyond these, smaller shelters dot the coasts – especially along Sweden and Finland – but details are mostly classified.

U-boats Since WW1

Submarines have prowled the Baltic since WWI. Imperial Russia built early U-boats and moored them in the Gulf of Finland; Germany lurked with U-boats in both World Wars. Even neutral Finland operated the submarine Vesikko in WWII, and later scuttled it under the 1947 peace treaty. Denmark kept a Cold War submarine force for Strait defence until scrapping it in 2004.

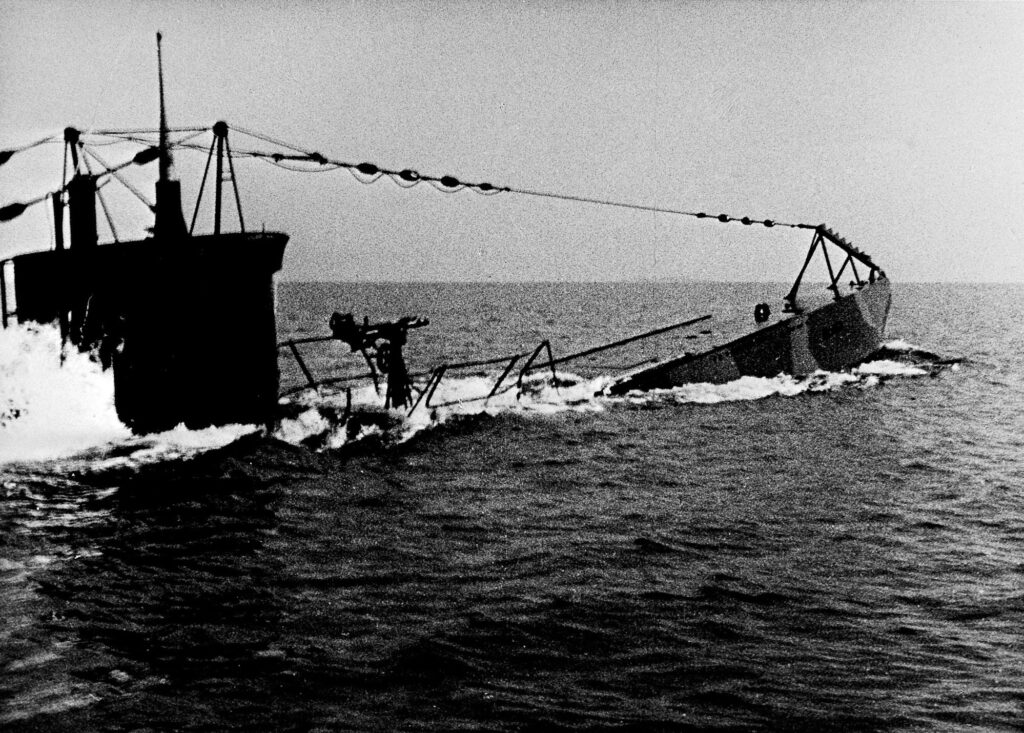

In 1981, there was the Whiskey on the Rocks incident a Soviet Whiskey-class sub (U-137) ran aground deep inside Swedish waters near Karlskrona, sparking a ten-day crisis. The Swedish Navy pulled it free, but the episode traumatised public opinion. It ingrained a belief that Russia will probe silently under the Baltic and Sweden must stay alert.

In 2022, the Nord Stream pipeline blasts, in Swedish/Danish waters, were followed by more leaks on Baltic cables and pipelines in 2023-24. Experts now warn that no undersea infrastructure is “safe by accident”. The Atlantic Council notes that since 2022, numerous cables and even a pipeline have been cut in what look like deliberate acts. NATO’s response has included 24/7 sea patrols and the Baltic Sentry mission.

A NATO Lake with Russian Teeth

Looking ahead to the 2030s, the Baltic Sea will feature a mix of ultra-quiet NATO subs and persistent Russian threats. On the Allied side, expect to see joint Swedish–Polish A26 patrols and surveillance. Germany’s Type 212s will be cycling in under NATO exercises. There will be periodic visits from U.S. P‑8 patrol aircraft and allied ASW forces as in Exercise Playbook Merlin 2025. By then, Sweden will have five modern AIP submarines (3 Gotlands + 2 Blekinges). With five submarines, Sweden can close the Baltic Sea, according to Sweden’s sub commander. Germany’s roughly ten Type 212 boats (current + future) will further reinforce the NATO undersea advantage.

Russia, for its part, will probably have a handful of diesels, a few Kilo-class and any new Lada variants, based in Kaliningrad and Kronstadt. Officially, Russia “continuously” builds more Kilos, so the Baltflot could see modest growth. But on paper, Allied subs will outnumber them by around 3:1. The question is whether Moscow can exploit hybrid tactics, such as deploying drones from “shadow fleet” tankers and cyber-sabotage of communication lines, to level the playing field.

Analysts already call the Baltic a “NATO lake” now that Sweden has joined. Yet it’s a shallow, crowded lake – and its bottom is raked by thousands of pipelines and cables. The quietest subs ever built will patrol those depths. As one NATO admiral puts it, the alliance’s multi-mission submarines will serve as undersea “eyes, ears and spears” in the Baltic. For all the focus on tanks and fighters, the real Baltic balance may be decided out of sight – in the darkness beneath the waves from Karlskrona and Gdynia, all the way to Kaliningrad and Kronstadt.

Read More:

- Reuters: Poland picks Sweden’s Saab to supply it with three submarines

- Breaking Defense: Poland selects Sweden’s Saab A26 as future submarine

- Breaking Defense: With Sweden, Baltic Sea now a ‘lake full of NATO submarines

- Breaking Defense: Denmark considering military submarines after almost 20 year gap

- Reuters: How Sweden and Finland could help NATO contain Russia

- Reuters: German defence minister seeks 4.7 bln euro deal to buy four submarines

- Atlantic Council: How the Baltic Sea nations have tackled suspicious cable cuts

- Stars & Stripes: NATO anti-submarine exercise in Baltic readies alliance for undersea conflict

- The Guardian: Swedish navy encountering Russian submarines ‘almost weekly

- Wikipedia: Baltic Fleet