The presidents of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have agreed in principle that if one Baltic state removes its railway connections to Russia and Belarus, the others will follow suit in unison. Meeting in Riga on December 4, 2025, the three leaders discussed dismantling the old 1,520 mm “Russian gauge” tracks that cross their eastern borders.

Unprecedented in peacetime, this dramatic step is being considered as part of “counter-mobility” defence measures to harden NATO’s eastern flank. No final decision has been made yet, but all three governments are studying the economic and security impacts with an eye toward a joint resolution in early 2026. Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda has even urged the EU to help fund what he calls a “Baltic Line of Defence,” fortifying borders and removing eastward rail links as a way to impede any future Russian military movement.

Officials stress that such moves must be coordinated regionally: “If we do it, we do it together,” as Estonia’s President Alar Karis put it. Latvia’s President Edgars Rinkēvičs likewise emphasised any track removal would be a collective decision and part of a broader package of anti-invasion tactics, not a standalone action. In Latvia, ministries and security agencies have been instructed to deliver an impact assessment by the end of 2025, after which national security councils can deliberate the next steps. By January 2026, the Baltic countries could be ready to formally approve ripping up these rails, which is a symbolic and literal break with their past dependence on Moscow.

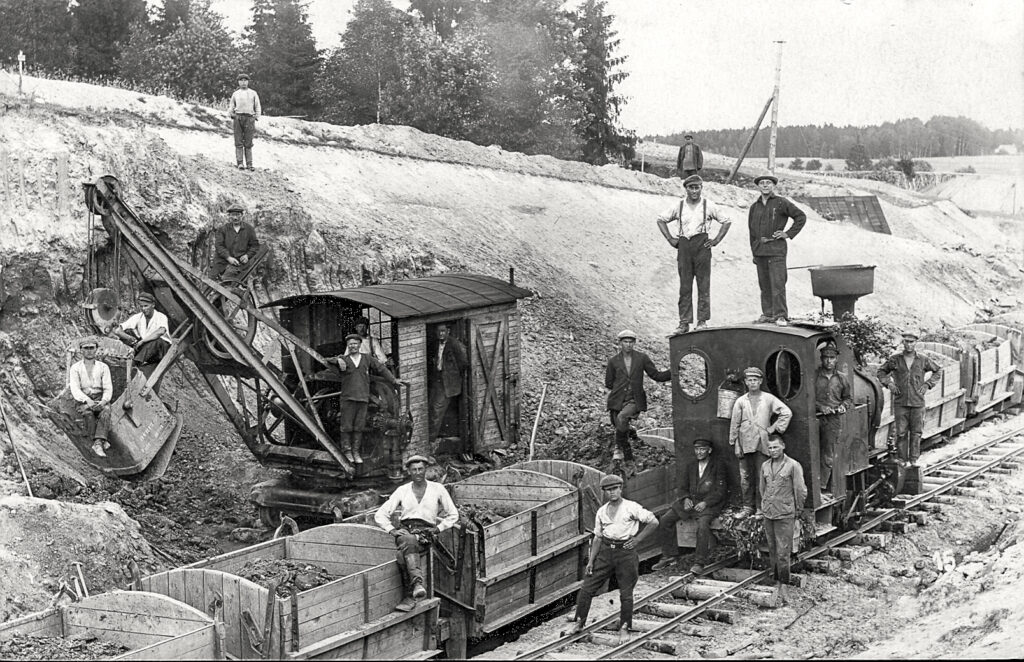

(Image: Szczureq / Wikipedia)

Cutting Off the Tracks

The proposal to physically remove the rail segments that run to Russia and Belarus would effectively cut the tracks at the borders. Supporters argue this would complicate any invading army’s logistics, since historically Russia has used railroads as the backbone of its military operations. The existing cross-border rails are a strategic vulnerability, providing a ready-made route for hostile forces. In Latvia’s case, the National Armed Forces recommended dismantling the little-used lines east of Daugavpils, saying “the sooner, the better,” because without rails “Russia’s ability to launch an invasion…would be significantly complicated”. The Latvian government acknowledges, however, that tearing up these tracks would also “completely stop the transit business”, including any remaining freight from Asia moving west via Russia. It’s a drastic trade-off between economic interests and security, reflecting how thoroughly the geopolitical calculus has changed since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

“Are they seeing a psychiatrist?”

Aleksander Lukashenko, commenting Baltic plans to dismantle railways to Russia and Belarussia

Not everyone is on board immediately. In Latvia, an opposition proposal to order immediate track demolition was voted down in parliament, with officials urging a careful, united approach instead. Belarus’s strongman Aleksander Lukashenko mocked the idea, asking, “As far as I know, some countries today are trying to dismantle railways to break ties with us and Russia, but the question arises – are they seeing a psychiatrist or not?” Yet the mere fact that the Baltic states are seriously debating such an irreversible step, severing rail lines laid in the 19th century, shows how deep the break with Russia has become.

Member of the Saeima Artūrs Butāns (National Alliance) pointed out that “we must not provide the enemy with ready-made infrastructure to use in the event of aggression.” He emphasised that analysis of the war in Ukraine clearly shows that “the railway has been the backbone of Russia’s war infrastructure, and we must not allow a similar threat in Latvia.” The National Alliance also urged the Latvian Prime Minister to secure funding at the European Union level to at least partially compensate for the costs of dismantling infrastructure, as part of strengthening the EU’s eastern border.

By uprooting the old tracks to the east, the Baltic nations are signalling that there will be no return to “business as usual” with Moscow. It is a final closure of the route back to the Russian sphere.

Tsarist Tracks With a 150-Year Legacy

To understand the significance of this move, one must remember that the Baltic region’s railways were originally built as part of the Russian Empire’s network. In the late 19th century, imperial authorities laid down broad-gauge, 5-foot, tracks across the provinces of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland – 1,524 mm apart, about 89 mm wider than European standard gauge. The choice of a different gauge, often dubbed “Russian gauge”, was no accident: it tied the Tsar’s western territories to St. Petersburg and Moscow, while making it harder for the railways to interconnect with Germany and Poland. By World War I, this gauge difference forced invading armies to stop and re-lay tracks, a defensive benefit the Russians exploited. Conversely, when Germany occupied the Baltics in both world wars, they hastily converted the rails to standard gauge, only for the Soviets to widen them again upon retaking the land. The result is that, even after 150 years, the iron pathways running from the Baltic Sea eastward still bear the imprint of imperial Russian engineering.

After World War I, Poland and Finland gained independence from the Russian Empire and faced choices about their rail systems. Poland, which had inherited a mix of Tsarist broad gauge and European standard lines, rapidly converted all former Russian tracks to standard gauge in the 1920s. By contrast, the three small Baltic republics, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, retained the 1,520 mm gauge on their railways, since their primary rail links at the time led toward the USSR and they had limited resources to rebuild. This decision was cemented after World War II, when the Baltics were occupied and incorporated into the Soviet Union. During the Cold War, the region’s railroads were fully integrated into the Soviet rail system, an east–west web oriented toward Moscow. The main lines ran from Russian heartlands to Baltic ports on the coast, moving Soviet troops and extracting Baltic produce. There was little development of north–south routes between the Baltic countries and Central Europe. Such connections were not in Moscow’s interest.

When the Baltics regained independence in 1991, they inherited an extensive, broad-gauge rail infrastructure that was largely intact. At first, this was a boon: Russian oil, coal, and fertiliser exports flowed by rail to Baltic seaports, providing lucrative transit revenue. For the better part of three decades, east–west cargo transit was a pillar of the Baltic economies. For example, Latvian Railways long depended on hauling Russian coal and oil to Riga and Ventspils, Lithuania’s port of Klaipėda thrived on Belarusian potash exports delivered by train. Even as the Baltic states joined the EU and NATO, they remained physically plugged into the ex-Soviet rail grid – a commercial link to the East that outlasted the political one.

All that began to change in the wake of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and especially after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Western sanctions sharply curtailed the flow of goods from Russia and Belarus. By 2024, the value of Baltic imports from Russia had collapsed to a tiny fraction of 2021 levels. The rail freight statistics are stark: Estonia’s state railway saw a 43% drop in cargo volumes in one year due to the loss of Russian transit traffic. Latvia’s rail freight plummeted as coal and oil transit dried up completely. Lithuania, under EU pressure, banned Belarusian potash trains to Klaipėda from February 2022, cutting off one of Minsk’s economic lifelines. With each passing month of the Ukraine war, the once-busy rail corridors running East-West have fallen silent, quiet steel pathways stretching to closed border checkpoints.

In some cases, physical dismantling has already started on a small scale. Lithuania, for instance, ripped up a spur line leading to a Belarusian fertiliser factory in 2022, to ensure that sanctioned potash could not be sneaked through. That removal, a short stretch of track literally torn out of the ground, was a test case for using rail infrastructure as leverage. Legal experts in Vilnius noted that no treaty explicitly forbids Lithuania from changing its domestic track gauge, as the 2002 Russia–EU–Lithuania transit agreement only covered simplified visa rules for Kaliningrad passenger travel, not a guarantee to maintain any particular rail line. In other words, there is no international law requiring the Baltics to keep these old Russian-gauge rails in place. The only barriers have been practical and economic. Now, with security the overriding concern, the political will exists to do what once seemed unthinkable: wrenching out the rails of empire, after a century and a half.

Rail Baltica: Building a New North–South Corridor

Even as they contemplate pulling up east–west tracks, the Baltic states are busy laying down new north–south ones. The flagship project Rail Baltica, a modern, European-standard high-speed railway from Tallinn to Warsaw, is well underway and slated for completion by 2030. This multi-billion-euro undertaking, 85% financed by the EU, will finally link Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania directly into the Western European rail network. Rail Baltica is being built at the standard gauge of 1,435 mm, literally a different track to the future. Its route runs north–south, joining the Baltic capitals to each other and to Poland, rather than radiating eastward to Moscow. “These two directions – Poland and the North – will ensure even greater security and economic attractiveness for us,” Lithuania’s Prime Minister Inga Ruginienė said at a recent meeting of Baltic PMs, underscoring the strategic value of the new line. Her Estonian counterpart added that Rail Baltica will bolster national defence as well as development, enabling NATO to move troops faster inside the region.

After years of slow progress, Rail Baltica is now gathering steam. Construction is underway on key sections, about one-third of the Estonian route is already being built. The prime ministers of all three countries insist the railway will be finished “on schedule” by the end of the decade. To silence any doubts, Latvia’s government just reaffirmed that it will not abandon the northern section toward the Estonian border, dismissing rumours that cost pressures might force a gauge compromise. Indeed, all main tracks of Rail Baltica across Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania will be European gauge, the core principle of the project. For the Baltics, this is more than just a transport upgrade. “Our critical infrastructure must be stronger and more resilient,” President Karis said, linking Rail Baltica to broader efforts to integrate with the West and secure the eastern flank.

Brussels views Rail Baltica through a security lens as well. The EU has a new Military Mobility fund to co-finance civilian transport projects that double as military infrastructure. Modern 1,435 mm tracks will allow NATO heavy equipment – tanks, artillery, armoured units – to deploy swiftly up and down the Baltics. Already, in military exercises, American Abrams tanks have been rolled off flatbed railcars in Latvia, demonstrating the deterrent effect of good rail links to the West. Planners often note that moving an armoured brigade by train is far faster and safer than by road convoy. Rail Baltica, once complete, means reinforcements from Germany or Poland could arrive in the Baltics within hours, not days. In a crisis, that could be decisive. As one security expert quipped, the cost of Rail Baltica, though in the billions, “might equal a few armoured brigades, but the railway could be what allows those brigades to arrive in time to matter”.

Beyond military mobility, the new line promises economic and social benefits: faster passenger travel, freight diversification, and an escape from the narrow trading patterns of the past. A container from Finland to Poland currently has to go by sea for two days or detour via Russia. In the future, it could “zip down Rail Baltica in a day”. Likewise, Baltic exporters will gain overland access to European markets, and vice versa, without the bottleneck of transhipping at gauge breaks or relying on vulnerable sea lanes. No wonder public opinion in the Baltics strongly supports Rail Baltica – not just for commerce, but as a kind of insurance policy that “they won’t be left isolated as in past dark chapters”, as one regional analysis put it. Steel rails running West mean solidarity: a tangible guarantee that these countries are linked to their EU allies come what may.

Running two parallel rail systems, one broad gauge, one standard, is an expensive luxury. For now, the Baltic states have little choice. They cannot abruptly scrap the old Soviet-gauge network because certain vital internal routes and industries still depend on it. For example, Poland and Lithuania have been using 1,520 mm lines to ship Ukrainian grain exports northward to Klaipėda during the war, avoiding Black Sea blockades. Local freight like timber, peat, and oil shale also still uses the legacy rails within the Baltics. Thus, in the medium term, the Baltics will operate two incompatible rail gauges side by side. This dual system entails maintaining separate rolling stock fleets and infrastructure – a costly arrangement, but one the EU is helping subsidise. In the long run, however, as broad-gauge usage dwindles further, the question will arise: do the old lines get converted or simply abandoned? The current trajectory suggests a phased drawdown of the broad-gauge network once Rail Baltica is fully functional and if relations with the East remain frozen. The tracks to Russia may first be mothballed, then removed entirely, as political circumstances dictate. In effect, one rail system is rising while the other falls into obsolescence.

Isolating Kaliningrad and Belarus

The Kremlin is watching with dismay as its former vassals quite literally pull up the rails that have tied them to Russia for generations. Nowhere is this more evident than in the case of Kaliningrad, the Russian exclave sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland. During Soviet times, Kaliningrad, formerly Königsberg, was connected to the motherland by a direct railway through Lithuania and Belarus. Even after 1991, Moscow secured agreements for continued transit: Russian trains have carried troops and goods across Lithuania’s territory to resupply Kaliningrad, under a special arrangement, with Lithuanian oversight. But if Lithuania dismantles the cross-border tracks leading into Kaliningrad, that land corridor would vanish overnight. The oblast, home to a million Russians and a major military garrison, would be cut off by rail. Any reinforcement or large-scale supply would then have to come by sea or air.

Kaliningrad has long been a double-edged sword: heavily armed, with Russia’s Baltic Fleet and nuclear-capable Iskander missiles, yet geographically exposed and reliant on goodwill for transit. With Sweden and Finland joining NATO in 2023–24, the Baltic Sea’s geography shifted in the West’s favour. The Baltic Sea has essentially become a NATO lake: All surrounding shores except Saint Petersburg and Kaliningrad now belong to NATO states, which could bottleneck Russian shipping in a crisis. The Suwałki Gap, that narrow 60-mile strip of land between Kaliningrad and Belarus, is another vulnerability for both sides: it’s the only land route by which NATO can defend the Baltics, and conversely the only route by which Russia could try to relieve a blockaded Kaliningrad. By tearing up the railroad that runs through the Gap, the Baltic states with Poland would force Russia to literally rebuild tracks from scratch if it ever wanted to drive trains through there again. Strategically, Kaliningrad would be sealed off. What was once a convenient forward base for Russia is turning into an island, a potential trap, should Moscow contemplate aggression.

Belarus, too, stands to be economically choked by the Baltic rail shutdown. For decades, Lithuania and Latvia provided Minsk with its cheapest outlets to global markets. Belarusian oil products, chemicals, and, famously, potash fertiliser flowed north by rail to Baltic Sea ports. That lifeline has already frayed: Lithuania halted Belarus’s potash exports in 2022 amid sanctions, forcing Belarus to reroute exports via Russian ports at great cost. If the remaining rail links at the border are physically removed, Belarus will have no direct rail access to the EU at all. Its only rail gateways west would be via Poland, where standard-gauge tracks from Poland meet broad-gauge tracks from Belarus at a few border points. Even there, freight must be laboriously transloaded or have its bogies changed due to the gauge break. Given the frosty relations and sanctions, Poland has already restricted Belarusian rail traffic and could easily sever it entirely in a crisis.

By losing the Baltic routes, Belarus becomes ever more tethered to Russia for trade. Minsk’s dictator Lukashenko, has bristled at this prospect, deriding the Baltics’ plans to tear up rails as lunacy. But there is little he can do. The tracks lie on Baltic sovereign territory, and no treaty guarantees their permanence. Belarus finds itself increasingly at Moscow’s mercy for access to world markets, a junior partner with shrinking options.

From the Baltic leaders’ perspective, these outcomes are not unintended side effects. They are part of the rationale. Deconnecting Belarus and Kaliningrad from EU infrastructure is seen as enhancing regional security. It eliminates the scenario of “business as usual” resuming with outlaw regimes. It also raises the economic pain for those regimes, as Belarus is discovering, which in theory could weaken their capacity for mischief. Most of all, in military contingency planning, fewer rail links into hostile territory means fewer vectors of attack. As Latvian MP Artūrs Butāns argued, one must not “provide the enemy ready infrastructure to use in case of aggression”. The Ukrainians learned this the hard way: Russia’s invasion forces relied heavily on rail supply lines. In the Baltics, any Russian offensive would likewise lean on rail if available, for moving heavy armour, fuel, and ammunition. Removing those tracks is akin to removing a highway bridge: it forces an invader to slow down, improvise, and depend on less efficient means. In conjunction with other defences, like blowing up roads or fortifying chokepoints, it could make the difference between a repelled attack or a rapid overrun. That is why the idea is couched as part of a holistic “Eastern Defence Line” concept, possibly extending down through Poland’s borders as well. It’s worth noting that Europe at large is now actively encouraging the gauge conversion and decoupling. A new EU regulation, the TEN-T revision, came into force in 2025, requiring member states with non-standard gauges (read: Finland and the Baltics) to “study, plan and promote” transition to 1,435 mm. EU funding is available for exactly such projects, recognising that infrastructure interoperability is a security issue. Even Ukraine and Moldova have begun pilot projects to build standard-gauge links out to the West.

Cut Off the Russian Electricity Grid

In February 2025, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania completed a long-planned transition away from the Russia-controlled electricity grid, officially synchronising with the Continental European electricity network.

Transmission system operators from all three countries cut their links to the Russian and Belarusian BRELL grid on 8 February 2025, a legacy system dating back to Soviet times, and operated briefly in isolation before final integration with Europe’s grid the next day.

European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) confirmed that the Baltic states’ power systems successfully matched frequency and stability standards with the broader Continental European Synchronous Area (CESA), the large network that serves more than 400 million customers across 24 countries. EU officials and Baltic leaders hailed the event as a major step in energy independence and resilience. The switch ends routine frequency control by Moscow and brings the Baltic markets deeper into the European internal energy market. Substantial EU funding under the Connecting Europe Facility helped finance the infrastructure upgrades necessary for the transition.

Finland’s Dilemma: An Island No More?

Although the focus is on the Baltic republics, Finland is quietly undergoing its own railway revolution. Finland still uses the same broad gauge (1,524 mm) it adopted under Russian rule in the 19th century. For decades, this was a footnote – Finnish and Russian trains could run between Helsinki and St. Petersburg with ease, the Allegro express, now running between Helsinki and Turku, and Finland’s freight networks had profitable links into Russia’s interior. But since 2022, Finland has cut off almost all rail traffic with Russia, those eastern lines sit almost idle. Now, as a newly minted NATO member, Finland is asking itself the same question as its Baltic neighbours: do we remain a broad-gauge enclave connected only to Russia, or do we rebuild our rails to connect with our allies? The answer from Helsinki is increasingly the latter.

In May 2025, Finland’s transport minister shocked many by announcing plans to convert Finland’s entire railway network to standard gauge. This would be a gigantic, decades-long project, as she said, costing tens of billions of euros. The government has set a deadline of July 2027 to decide the timeline and scope of the gauge shift. In the meantime, Finland is starting with a more immediate goal: building Rail Nordica, a standard-gauge connection from the Baltic Sea to the Arctic Ocean via Lapland. The first stage, already funded, will construct about 30 km of 1,435 mm track from the Swedish border (Haparanda/Tornio) to Kemi in northern Finland. This seemingly small segment is actually the keystone of a grand design: eventually extending standard gauge south to Oulu and even Rovaniemi, and west via Sweden all the way to Narvik, Norway, an ice-free Atlantic port. The strategic logic is compelling. As Minister Lulu Ranne noted, Finland “will never again be in a situation where we can’t get help into Finland or cannot get to Europe via railway”. During the Cold War and even up to 2022, Finland’s supply lines were vulnerable. 90% of its defence equipment arrived by sea through the Baltic. If that sea is contested, a very realistic scenario now, Finland would become an island. Rail Nordica and related projects ensure an alternate land route to Western Europe through the Nordics, bypassing the Baltic Sea altogether.

Finland’s pivot northward has come at the expense of some domestic dreams. A proposed high-speed rail (“One-Hour Train”) between Helsinki and Turku – once the marquee rail investment – is now on the back burner, with many questioning its priority “in this geopolitical situation”. Ranne has even mused that if the Turku line does proceed, it might be built to standard gauge from the outset. That idea is controversial. It would create an awkward, isolated pocket of standard gauge in the south, but it shows how Finland’s mindset has flipped. A few years ago, an official report flatly concluded that gauge conversion was not cost-effective. Now, after Ukraine’s wake-up call, the government is actively planning for it. By starting in the north around 2030 and working south over decades, Finland envisions a gradual transition, potentially using dual-gauge tracks in some corridors to ease the changeover. EU support is crucial – Brussels could fund 30–50% of the costs – and Finnish officials emphasise the economic co-benefits, such as job creation and regional development, to sell the plan domestically. Still, technical challenges abound (locomotives, tunnels, and platforms all need adapting), and not everyone in Finland is convinced the massive expense is justified purely by security. Yet, given NATO’s backing and the new TEN-T rules nudging toward gauge standardisation, it appears the writing is on the wall for Russian gauge in Finland. As one Finnish official put it, the question is no longer if but “in what timeframe and to what extent” the shift will happen.

By synchronising its rails with Sweden and the Baltics, Finland will firmly anchor itself in the Western logistics network. The vision of a “Nordic–Baltic backbone” is starting to materialise: a continuous standard-gauge corridor from the Arctic, through Finland and Estonia, perhaps one day via an undersea tunnel, down through Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, into the heart of Europe. This is essentially the Three Seas Initiative by rail, knitting together North–South infrastructure in a region that was previously only linked East–West under Moscow’s design. The broader strategic consequence is that Russia and its ally Belarus are being walled off from Europe’s core transport arteries. It’s a reversal of fortune engineered not by soldiers, but by engineers and statesmen laying track and pouring concrete. Putin’s ambition to reintegrate the post-Soviet space has instead been answered by a further disintegration – the physical uncoupling of former Soviet republics from Russia’s orbit.

End of the Line for the “Moscow Express”

As 2026 dawns, the Baltic states stand ready to make a momentous decision: permanently severing the rail links to their former imperial master. What once would have been a heretical idea – tearing up functioning railroads – now feels like the logical culmination of a long journey west. The war in Ukraine has brutally clarified that the old connective tissue of the Soviet era is now a security liability. By ripping out tracks, the Baltics are ripping off the Band-Aid – ensuring there is no easy route back to the old ways of dependent trade or Russian troops rolling in on rails. It is a point of no return.

Psychologically, the impact cannot be overstated. For generations, Baltic train timetables ran on “Moscow time,” both literally and figuratively. The timbers and steel of those tracks carried not just freight, but the weight of imperial dominance and Soviet occupation. Dismantling them is an act of historical catharsis, closing the chapter on 150 years of being tied into Russia’s infrastructural grid. In their place, new connections are being forged: to Warsaw, Stockholm, Helsinki, and beyond. Where rails once pointed East, they now point West and North. This is integration in the truest sense, aligning with Europe not only politically and economically, but physically, on the ground.

Practical challenges remain. The Baltic countries will need significant EU funding to mitigate the economic hit of losing transit fees and to build out alternative logistics. They must manage the logistics of running dual gauges during the transition and help their rail companies adapt or downsize from the loss of eastern freight. There are also environmental and local economic questions – unused rail corridors can disrupt communities if abruptly closed. These issues will require careful handling and likely some “solidarity payments” from the EU, much as the EU is helping with energy decoupling costs. But given the strong consensus in Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius – and growing support in Helsinki – the political momentum is on the side of those who argue that security trumps transit revenue. In the words of an Estonian defence analyst, spending money on rails that connect allies is “as important as spending on weapons”, because one without the other could render both useless.

When the Baltic presidents and EU officials finalise this decision, likely in the coming weeks or months, it will mark the end of the line for the old “Moscow – Baltic” railway. The tracks that carried Tsar Nicholas I’s soldiers, Stalin’s deportation trains, and Brezhnev’s supply freights will be consigned to museums and memories. In their stead, new high-speed trains will one day speed along Rail Baltica, filled with Baltic, Polish and Finnish passengers heading to European destinations without ever crossing into unfriendly territory.

Ironically, Putin’s war – meant to pull ex-Soviet lands back into Moscow’s orbit – has instead accelerated their iron rails pointing firmly West. The rails of empire are being pulled up, and in their place, a new iron silk road within NATO is being laid down. This is geopolitical tectonics in action, measured in track gauges and travel times.

Rail Baltica is a route that, for the first time in history, unites the Baltic region internally and with its European neighbours, rather than binding it to the East. The message to Moscow is unmistakable: that train has left the station.

Read More:

- International Railway Journal: Baltic States to dismantle cross-border rail links to Russia and Belarus?

- The Baltic Times / LETA: Baltic presidents unanimous on need for coordination on dismantling of rail tracks

- LSM (Latvian Public Media): Baltijas valstu līderi pārrunājuši iespēju vienlaicīgi nojaukt sliedes pie Krievijas un Baltkrievijas robežām (Latvian)

- LSM / TV3 “Nekā personīga”: Vairākas ministrijas un drošības iestādes gatavo atzinumu par sliežu nojaukšanas Krievijas pierobežā ietekmi (Latvian)

- Jauns.lv: “Viņi pie psihiatra iet?” Lukašenko reaģējis uz iespējamo Latvijas dzelzceļu demontāžu pie robežas ar Krieviju un Baltkrieviju (Latvian)

- LRT (Lithuanian National Radio/TV):“Teisės ekspertai skirtingai vertina siūlymus išardyti rusiškus bėgius: klausimų kyla dėl tarptautinių įsipareigojimų” (Lithuanian)

- LRT English / BNS: Baltic PMs say Rail Baltica will be completed on time

- ERR News (Estonia): Estonian minister rejects rumors Latvia wants to keep Russian gauge on Rail Baltic

- Yle News (Finland): Minister: Finland plans to change its track gauge to European standard

- Yle News: Finland invests in future rail link to Norwegian Sea

- Jamestown Foundation – Eurasia Daily Monitor: Finland, Sweden, and Norway to Build a Railway to Transport Troops and Weaponry to Russian Border

- Nordic Defence Review: Ripping Up the Rails of Empire: Baltic and Finnish Railways Turn Westward

- Brookings Institution: Why is Kaliningrad at the center of a new Russia-NATO faceoff?”