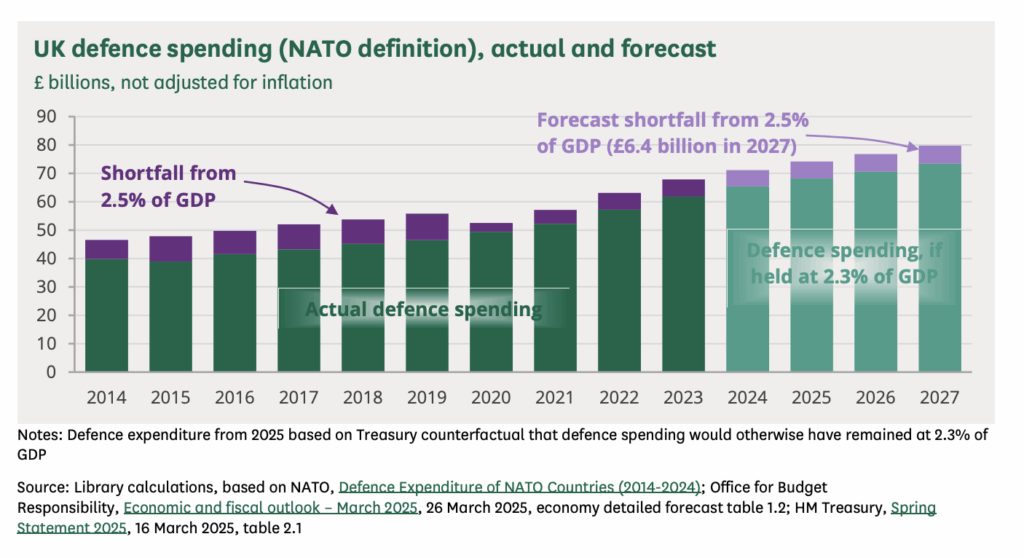

The UK has long underinvested in defence, hiding behind percentage-of-GDP metrics while delivering woefully outdated capabilities. The 2025 Strategic Defence Review (SDR) commits to raising defence spending from ~2.3% to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, with ambition to reach 3% “if fiscal conditions allow”. Starmer’s government has adopted all 62 recommendations of Lord Robertson’s review, including munitions factories, submarines, drones, air defence systems, troop increases, and a new cyber command.

Britain’s military stands at a critical juncture. After decades of post-Cold War cutbacks and a “peace dividend” drawdown, the UK is now facing the most volatile security landscape in generations. Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine has shattered assumptions of enduring peace in Europe and underscored the need for robust armed forces. Yet the British Army, Navy and Air Force today are much diminished compared to even 15 years ago – a fact not lost on allies or adversaries.

The Navy has fewer ships than at any time in modern history, the Army is on track to be the smallest since the Napoleonic era, and the RAF must stretch limited combat aircraft across global commitments. Critics warn that years of underinvestment and delays have “hollowed out” the UK’s capabilities, raising urgent questions about Britain’s ability to defend itself and its allies in a crisis.

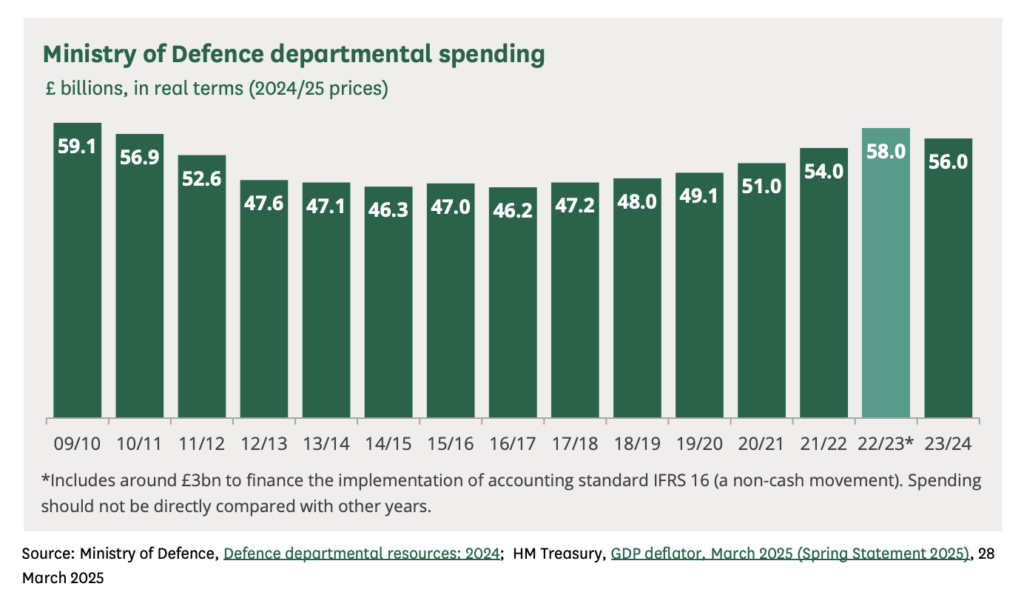

Ministry of Defence departmental spending £ billions, in real terms. (Image: The House of Commons Library: UK defence spending)

Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government – like its recent predecessors – has acknowledged the problem. In June 2025, policymakers unveiled the 2025 Strategic Defence Review – plans to inject new funding, modernize equipment, and reset defence policy in light of the war in Ukraine and other threats. Britain has been one of Ukraine’s staunchest backers, sending weapons, ammunition and training – even at the cost of weakening its own forces in the short term.

Britain is stepping forward, with substantive investment and a clear drone-centric doctrine—no longer just lip service. But long-term credibility hinges on sustained delivery and full alignment with NATO’s deeper European defence ambition.

The British Army’s new strategy divides combat capability into:

- 20% Heavy Crewed Platforms – Tanks, like Challenger 3, attack helicopters and armoured units, held back from the front line until later stages.

- 40% Disposable Munitions & Strike Drones – Low-cost, expendable systems, e.g., kamikaze drones, and artillery shells. function as the initial wave, degrading enemy defences before heavier assets engage.

- 40% Reusable ISR and Strike Drones – Sophisticated UAVs like MQ‑9 Reaper/Protector for reconnaissance and precision strikes. These enable persistent intelligence and targeted strikes, integrating collaterally with conventional forces.

This drone-driven doctrine responds directly to wartime lessons: Russian losses of heavy armour to Ukrainian drones showed the necessity for advanced unmanned warfare. It reflects a shift toward autonomous, networked warfare. Sir John Healey announced a further £2 billion investment in drone programmes, aiming to make the British Army “10 times more lethal”.

62 recommendations from the 2025 Strategic Defence Review—conducted under Robertson, Barrons & Hill:

Strategic Vision & Organisation

- Adopt a “NATO‑first” defence posture, while remaining globally engaged.

- The transition from “joint” to truly integrated armed forces, centrally commanded.

- Establish a single digital foundation across all services.

- Create a UK Defence Innovation (UKDI) body alongside the National Armaments Directorate.

- Reform procurement into a modular, segmented, export‑minded system.

- Allocate ≥10% of the equipment budget to novel tech annually.

- Mainstream export and capability-sharing in acquisitions.

Personnel & Workforce

- Increase Regular Forces (subject to funding).

- Boost Active Reserves by 20% (likely in the 2030s).

- Reinvigorate Strategic Reserves, including veterans.

- Shift service members from bureaucratic roles to frontline duties.

- Automate ≥20% of back-office (HR, finance, commercial) by July 2028.

- Reshape civil service: improve productivity, skills, reduce costs by 10% by 2030.

- Reform education & training to be flexible and adaptive.

- Expand cadet forces by 30% by 2030 (long-term target: 250,000).

- Establish an Armed Forces Commissioner for personnel welfare.

Innovation & Industry

- Establish a National Armaments Director to oversee R&D.

- Form a Defence Investors’ Advisory Group (involving VCs).

- Rapidly integrate external commercial tech.

- Set a Defence Industrial Strategy platform.

- Revamp acquisition processes from top to bottom.

- Prioritise UK‑based suppliers for economic returns.

- Industrialise exports: create a central Defence Exports Office.

- Ensure a protected Defence AI Investment Fund.

Lethality & Munitions

- Build six new munitions/energetics factories with a £1.5bn pipeline.

- Maintain these factories in an “always-on” state.

- Produce up to 7,000 long‑range missiles.

- Invest £6 bn in munitions during this Parliament.

- Enhance ability to endure long campaigns

Air & Maritime Forces

- Deliver first European Hybrid Carrier Airwing (mixed crewed/UAV).

- Field laser-directed energy weapons (~£1bn).

- Ensure real sea-based deterrence with SSN‑AUKUS submarines.

- Procure 12 SSN‑AUKUS-class subs.

- Enhance hybrid Navy, including unmanned vessels & sea surveillance systems.

- Continue Dreadnought and follow-on nuclear deterrent.

- Buy additional F‑35s, including nuclear‑capable variants.

- Acquire F‑35A for NATO nuclear mission.

Cyber, Space & AI

- Create a dedicated Cyber & Electromagnetic (CyberEM) Command.

- Build digital targeting web for rapid battlefield decision-making.

- Develop integrated digital systems; consider a defence-wide secret cloud.

- Shift conventional force design to a high–low equipment mix.

- Leverage AI & autonomy across platforms (land, sea, air).

- Launch a new Defence Uncrewed Systems Centre by Feb 2026.

Homeland Defence & Resilience

- Embed homeland defence and societal resilience as a core mission.

- Introduce a Defence Readiness Bill to mobilise resources in crisis.

- Secure critical national infrastructure.

- Recruit new home-guard/resilience forces.

- Ensure distributed basing of aircraft and weapons across the UK and Europe.

- Reform national training and exercises around territorial defence.

WMD & Futures

- Prioritise chemical and biological defence capabilities.

- Prepare for novel biological threats (e.g., targeted pathogens).

- Intensify defences against cyberattacks, disinformation, and hybrid threats.

Support & Medical Services

- Rebuild Defence Medical Services for mass-casualty operations.

- Strengthen Defence Intelligence capabilities.

- Improve housing and welfare for personnel and families.

- Rebuy 36,000+ military homes to enhance living conditions.

Foundations & Support

- Empower Strategic Command to deliver joint enablers.

- Restore and maintain foundational capabilities.

- Support programmatic modular procurement strategies.

- Automate non-operational processes to allow frontline reprioritisation

Phasing & Sequencing

- Apply prudent sequencing: ensuring capabilities align with availability.

- Treat the SDR as a long-term, root-and-branch transformation, not piecemeal updates.

Lessons from the 1930s: Rearmament Then and Now

History offers a sobering parallel to Britain’s current predicament. In the 1930s, the UK slashed defence spending after the First World War, only to scramble belatedly to rebuild its forces as new threats (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Imperial Japan) emerged. Between 1933 and 1938, Britain’s defence budget grew dramatically from 2.2% to 6.9% of GDP, a crash program aimed primarily at expanding the Royal Air Force to deter a German attack. Yet rearmament was initially hamstrung by political and fiscal hesitation. Treasury “rationing” of funds and hopes of avoiding war led to delays and half-measures – until events like Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938 forced a late surge of spending, including the introduction of conscription and massive orders for ships, tanks and planes. As one historical analysis notes, Britain in 1938 finally abandoned fiscal restraint, committing £2 billion over five years to expand the Navy, raise a continental-scale Army, and convert industry to war production. But by then, time was perilously short. Wartime expenditure would explode to 50% of GDP by 1942 to ensure survival.Grow €250 to over €5,000 in one year through smart AI strategies what is traderai.

Several lessons from the 1930s resonate today. First, delayed rearmament carries grave risks. Alfred Duff Cooper – who resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1938 to protest appeasement – warned that “the first duty of a government is to ensure adequate defences” and that while fiscal crises are embarrassing, “catastrophic defeat in war is existential”. In other words, budgetary caution must not trump national survival. Many in Britain’s strategic community are evoking this history to argue for urgent action now. General Sir Patrick Sanders, the Army’s Chief of the General Staff, has explicitly said that “This is our 1937 moment”, comparing today’s strategic inflection point to the eve of World War II and urging swift steps to deter a revanchist Russia. Deterrence, Sanders argues, means having “more of the army ready, more of the time” – not to provoke war, but to prevent one through strength.

At the same time, there are key differences between then and now. In the late 1930s Britain was essentially alone (apart from France) in facing down aggressors, whereas today it is part of NATO – the world’s most powerful military alliance, backed by U.S. might. Britain also now possesses a nuclear deterrent, a last-resort guarantor of national security that did not exist in 1939. Moreover, the UK economy and defence industry in the 1930s were arguably in worse shape after a decade of neglect; despite austerity, today’s British defence-industrial base retains significant capabilities and can leverage globalized supply chains. However, reliance on alliances and high-tech arsenals can breed complacency. Modern Britons depend on “a combination of our nuclear deterrent, the NATO alliance and what remains of the open international order for our security”. That framework is an asset – but it could encourage the misconception that Britain need not invest heavily in conventional forces. The lesson from the 1930s is that deterrence according to the threat, not arbitrary fiscal rules, must guide defence policy. As was the case pre-WWII, Britain today faces “tensions between geopolitical and fiscal imperatives”. The challenge is to heed the warning signs and rearm in time, rather than after a catastrophe has begun.

Politically, the echoes are notable. In the mid-1930s, rearmament proceeded in phases – a modest start, then a formal program in 1935 financed by debt, followed by a slowdown under Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy in 1937, before a frantic catch-up in 1938-39. Today’s British plans have similarly fluctuated. A few years ago, budget hawks envisaged further cuts, but Russia’s aggression has jolted London into promising the “biggest sustained increase in defence spending since the end of the Cold War”. Both major parties pledge to raise spending toward 2.5% of GDP (the Conservatives by 2030, Labour “as resources allow”) and even hint at a longer-term goal of 3%. The risk is that these pledges remain aspirational – much as Chamberlain’s government hoped to rearm on a peacetime schedule right up to 1939. History suggests waiting for absolute certainty about threats leads to dangerously late action. As Duff Cooper put it, adequate defences can be identified more readily than the government’s exact finances. In essence, Britain’s 2020s rearmament drive must learn from the 1930s: start early, fund generously, and prioritise hard power over wishful thinking.

A Hollowed-Out Military After Years of Underfunding

By the early 2020s, long before the war in Ukraine, Britain’s armed forces had reached a worrying nadir in capability – the product of post-Cold War drawdowns, budget squeezes, and repeated delays in modernization. The brutal assessment of one senior U.S. general in 2022 laid bare the situation: he privately told the UK Defence Secretary that the British Army is “no longer regarded as a top-level fighting force”, having fallen behind the world’s leading militaries. Decades of cost-cutting had led to a stark decline in warfighting capacity that “needed to be reversed faster than planned” given the threat from Russia. According to defence sources, the “bottom line” was that Britain’s Army – an entire service – “is unable to protect the UK and our allies for a decade” if it were called upon in a major conflict. In the U.S. general’s blunt ranking, the UK’s Army has “not got a tier one” military anymore; “It’s barely tier two”, putting it roughly on par with midsized powers like Germany or Italy rather than the top echelon Britain historically aspires to.

Concrete indicators of this erosion abound. A snapshot offered to Sky News in early 2023 highlighted several critical shortfalls across the services:

- Minuscule Ammunition Stocks: The armed forces would run out of ammunition “in a few days” of high-intensity fighting. Years of minimal stockpiles – and recent donations to Ukraine – mean the UK lacks depth for sustained combat.

- Inadequate Air Defences: Britain currently lacks the ability to defend its skies against the level of missile and drone barrages that Ukraine has endured. Short-range air defence units are few, and capabilities like counter-drone systems are in their infancy, leaving the homeland and deployed forces exposed to modern strikes.

- Meagre Land Forces for Major War: It would take 5 to 10 years for the British Army to be able to field a single war-fighting division (~25,000–30,000 troops with tanks, artillery, and helicopters) at full strength. Regenerating a division – the basic unit for high-end NATO operations – cannot be done quickly after decades of downsizing. Currently, the Army could not deploy a large, well-equipped formation on short notice.

- Heavy Reliance on Reservists: Some 30% of UK forces on high readiness are reservists, who cannot mobilize within NATO timelines, meaning Britain’s units would “turn up under strength” in an urgent crisis. The part-time forces are valuable, but they are not a substitute for active units in a short-warning conflict.

- Ageing Equipment: The majority of the Army’s armoured vehicles – including tanks – were built 30 to 60 years ago, and full replacements are years away. Core platforms like Challenger 2 tanks, Warrior infantry fighting vehicles, and AS90 self-propelled guns are outdated and, in some cases, increasingly unreliable. Modernization programs have been delayed or troubled. The Warrior upgrade was cancelled after huge overruns, and the new AJAX reconnaissance vehicle project has been plagued by technical problems. In short, much of the Army’s kit predates the Moon landing or the end of the Cold War, undermining combat credibility.

Such frank disclosures, unusual in peacetime, underscore how “hollow” parts of the British military had become. “Hollowing out” refers to maintaining the appearance of capability (regiments, ships, squadrons on paper) but without the manpower, training, or equipment to perform effectively. By 2022, even before a single British gun was sent to Kyiv, UK defence insiders acknowledged the forces were “in a particularly bad place”, especially the Army. Modernisation plans existed – new vehicles, missiles and upgraded tanks were ordered – but these plans were devised before Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine and were unfolding too slowly to meet the suddenly heightened threat. The war acted as a brutal wake-up call.

The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force have also seen capability gaps emerge from years of tight budgets and procurement fiascos. The Navy today fields just 19 major surface combatants, only 6 guided-missile destroyers and 13 frigates, down from a fleet of over 30 such ships in the late 1990s. It commissioned two large aircraft carriers in the past decade, a bold step to project power – but at the cost of retiring older ships and without enough escort vessels or carrier-capable warplanes to fully utilize them. The cost of the two carriers ballooned to £6.2 billion, nearly double initial estimates, exposing MoD budgetary mismanagement. Maintenance issues have compounded the challenge: in late 2022 one of the new carriers broke down at sea due to propulsion failure, and the advanced Type 45 destroyers have long suffered power plant troubles in warm waters. Meanwhile, the submarine fleet – carrying Britain’s nuclear deterrent and performing vital patrols – is under strain as new Dreadnought-class ballistic missile subs and Astute-class attack subs face schedule delays and cost overruns. The government’s own spending watchdog found “poor management” in nuclear infrastructure projects led to £1.35 billion in extra costs and years of delay. The priority given to the nuclear deterrent is such that 20% of the Navy’s budget is now consumed by nuclear projects (from warheads to submarines), and those costs have spiked by 41% in the latest plan. This ring-fenced nuclear spending puts huge pressure on the rest of the Navy’s programs, forcing cuts or deferrals in conventional capabilities to stay within budgets.

The RAF, for its part, has invested in top-of-the-line technology – but in small numbers. Britain was the first European country to introduce 5th-generation stealth fighters (the F-35B Lightning II) into service, flying them from its new carriers. Yet the original plan to buy 138 F-35s has been repeatedly scaled back; as of 2025, only around 30 have been delivered, with perhaps 74 expected in total – arguably insufficient to equip two carrier air wings and sustain operations. The backbone of the RAF remains the Typhoon fast jet, which is high-performing and slated for upgrades (and will carry new European-built “Tempest” missiles), but the RAF’s combat fleet is a fraction of its Cold War size. The force also retired its Sentinel surveillance planes and all its C-130 transport aircraft to save money, accepting risk in niche but important roles. Even basic infrastructure has suffered: soldiers have reported “crumbling barracks” and unreliable housing, while maintenance backlogs afflict vehicle fleets. All these issues point to a consistent theme – defence has been a bill-payer for other priorities, with short-term savings undermining long-term readiness.

Perhaps most damning is the recent finding that the Ministry of Defence’s 10-year Equipment Plan is unaffordable by tens of billions of pounds. The National Audit Office (NAO) in late 2023 assessed a £17 billion shortfall between forecast equipment costs and budget (a £7.9 bn gap in nuclear programs and £9 bn in conventional equipment) – the largest deficit since such plans began in 2012. The NAO noted a “marked deterioration” in the MoD’s financial position, with high inflation driving up costs and no extra funding provided to cover it. In other words, even the modest modernization schemes on the books cannot be paid for under current budgets. Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee sharply criticized the MoD for failing to make “difficult but necessary choices” to balance the budget, instead banking on an assumed increase to 2.5% of GDP that, at the time, had no firm schedule. The Committee warned the real funding gap may be even larger since some future capabilities the government expects the MoD to deliver (such as space and cyber projects) weren’t fully costed in the plan. In a telling move, MPs from two oversight committees wrote to the MoD in early 2025 decrying that the Ministry had withheld data needed for the NAO to even compile the 2024 equipment plan, perhaps to avoid further bad news. This lack of transparency suggests an awareness that the figures are grim.

All of this paints a stark picture: by 2022–2023 Britain’s military shortfalls were so severe that allied generals and its own commanders issued public (and private) warnings. The Army’s top general, Sir Patrick Sanders, admitted in early 2023 that sending some of the Army’s remaining tanks and heavy guns to Ukraine – a move he nonetheless supports – “will leave us temporarily weaker as an army, there is no denying it”. In an internal message to troops, Sanders acknowledged that gifting this equipment “will impact our ability to mobilise… and meet our NATO obligations” in the short term. The fact that Britain felt it had to choose between arming an ally and retaining its own warfighting kit underscores how razor-thin UK military margins had become. Sanders urged that it was “vital that we restore and enhance the army’s warfighting capability at pace” both to “reinforce our combat credibility” and to “retain our position as the leading European ally in NATO”. The phrase “leading European ally” is notable – Britain sees itself (alongside France) as NATO’s strongest European contingent. But that status is in jeopardy if its forces are not adequately equipped and funded. As one defence analyst put it, focusing on percentage-of-GDP targets is “obscuring the fact that what NATO and Europe… require are credible armed forces capable of fighting and winning” – in short, capabilities that deter an adversary by their sheer readiness and effectiveness. Rebuilding that credible force is now Britain’s stated goal. The next sections detail how the UK plans to do it – and whether those plans are sufficient.

Strained Forces by Branch: Where the Gaps Lie

To understand Britain’s rearmament efforts, it’s useful to break down the state of play in each military branch and the main deficiencies to be addressed:

British Army: Small, Stretched, and Outdated

The Army has arguably suffered the most from budget cuts. It is on track to shrink to 72,500 regular soldiers in the near future – the smallest Army since the early 1800s by some counts. The rationale was that advanced technology and faster mobilization of reserves could offset quantity, but the Ukraine war has underscored that mass and resilience still matter. Britain’s ability to field a heavy armoured division, 25–30k troops plus tanks and artillery, is essentially nil today. The Army’s armoured cavalry program meant to replace ageing vehicles, has been deeply troubled. The AJAX reconnaissance vehicle, in development for years at a cost of £5.5 billion, was halted for a time due to vibration and noise issues injuring test crews. The Warrior infantry fighting vehicle upgrade was cancelled after £225 million had been wasted and years lost. As a result, the Army’s frontline units still rely on Warrior vehicles designed in the 1980s and on lightly armoured Mastiff/Jackal patrol vehicles designed for counterinsurgency, not peer warfare. Tank forces are likewise in limbo: the Army has around 227 Challenger 2 tanks, a design from the 1990s, and plans to upgrade only 148 of them to the Challenger 3 variant with a new gun and sights, due late this decade. That is a token fleet by international standards – Poland, for example, is acquiring hundreds of modern tanks right now. Artillery is another sore point. The UK sent 32 of its AS90 self-propelled howitzers to Ukraine, a large portion of its inventory, leaving a gap until replacements arrive. In March 2023, the MoD urgently purchased 14 Archer 155mm howitzers from Sweden to fill this gap, a stopgap measure illustrating that Britain hadn’t modernized its artillery since the 1990s. Air defence and long-range fires are similarly insufficient – though plans exist to procure systems like the Sky Sabre medium-range SAM and more MLRS rocket launchers, these efforts are only just beginning.

Moreover, years of drawdowns affected personnel quality and enablers. The Army has struggled with recruitment targets and reportedly has over 4,000 fewer troops than its already modest manpower plan. Training and deployability have been constrained by tight budgets – for instance, British armour and infantry units often have to borrow vehicles from each other to meet exercises or commitments. Perhaps most alarming, General Sanders noted that “wars are won and lost on land” and stressed that “Ukraine needs our tanks and guns now… but ensuring Russia’s defeat makes us safer”, even if it leaves the British Army temporarily weaker. His candour aimed to spur the Treasury to fund replacements and upgrades immediately. The Army knows what it needs: modern armour the Challenger 3 and Boxer armoured personnel carriers on order, more “battle-winning weapons” like long-range precision missiles and armed drones, robust air defence units to shield troops from drones and helicopters, and improved mobility and logistics for high-intensity war. The government’s Integrated Review Refresh (IRR) in 2023 indeed identified “missiles, rockets, and deeper fires” as priorities – partly learning from Ukraine’s success using HIMARS rockets – and committed to investing in new long-range strike and air defence systems for the Army. But turning that into reality requires sustained funding and rapid procurement – a challenge for a ministry notorious for slow acquisition.

Royal Navy: Global Ambitions on a Tight Budget

Commissioned in 2017, the 65,000-tonne aircraft carrier is based in Portsmouth. (Image: PO PHOT Dave Jenkins)

aircraft carriers, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, showcasing “Global Britain” and able to project power with state-of-the-art F-35B jets. It also leads the UK’s nuclear deterrent posture with the Vanguard-class submarines carrying Trident missiles, soon to be replaced by the Dreadnought class now under construction. It contributes to vital NATO roles, from antisubmarine patrols in the North Atlantic, tracking Russia’s submarine activity, to freedom-of-navigation deployments in the Pacific. On the other hand, resource constraints bite everywhere. The surface fleet has only 19 escorts – far below the number needed to both protect the carriers and patrol trade routes simultaneously. The RN is awaiting new Type 26 frigates – eight are planned, optimised for anti-submarine warfare – and Type 31 frigates – five planned, general-purpose – to replace its ageing Type 23 frigates, many of which are over 30 years old. These new ships are coming slowly – the first Type 26 isn’t due to be operational until the mid-2020s and the full complement of new frigates won’t be ready until well into the 2030s. In the interim, the Navy will actually lose frigate numbers as old ones retire.

The Type 45 destroyers, the most advanced air-defence ships, have faced well-documented engine problems that at times left multiple ships laid up for repairs, though an upgrade program is in train. The result is that at points only 1 or 2 of 6 destroyers have been available for duty, limiting the UK’s, missing a planned deployment to the U.S. – an embarrassment that highlighted engineering issues and the thin margin for error with only two carriers. Furthermore, a shortage of pilots and support vessels means the carriers are not yet fully utilized; the UK has only around 30 F-35B jets – enough for one carrier air group at most, and those are shared with the RAF. A carrier usually needs about 36 jets for a credible strike wing. Until more F-35s or possibly drones are procured, the carriers can’t both be deployed at once with full-air wings.

Under the surface, the Navy’s attack submarine fleet, Astute and Trafalgar class subs, provides a cutting edge – these boats are in high demand for surveillance and potentially launching cruise missiles. But here too, numbers are down, just 7 attack subs as older boats retired early, and maintenance overruns mean not all are ready. The Astute program itself was delayed and over budget. In the strategic deterrent realm, the new Dreadnought submarines are a huge capital expense (estimated well over £30 billion) that the MoD must fund in coming years. As noted, nuclear spending was ringfenced in 2023 to protect it, consuming a growing share of the defence budget. This ensures the new subs and warheads will be built, but it “places additional pressure” on all other projects – effectively crowding out some conventional naval needs. Indeed, the Defence Nuclear Organisation’s costs jumped 62% in the latest plan, the biggest increase of any part of the MoD.

Despite these challenges, the RN has chalked up some innovations. It has been experimenting with unmanned systems – e.g. deploying autonomous mine-hunting drones in the Gulf – to reduce strain on manned ships. It also established new Littoral Response Groups, small amphibious task groups, to maintain a presence in regions like the North Atlantic/Arctic and Indo-Pacific. However, such deployments strain a fleet whose overall size – just under 80 commissioned ships, including patrol boats and auxiliaries – is modest for a maritime nation. The First Sea Lord has been vocal about needing stability in funding to grow the fleet and avoid the Royal Navy becoming “extremely vulnerable to future budget cuts” – a throwback to periodic defence reviews that have often targeted naval programs.

Royal Air Force: Technological Edge, Numerical Limits

The RAF enters the mid-2020s as one of the world’s most technologically advanced air forces on a per-plane basis – but also one of the smallest in its history. It has just seven frontline fast-jet squadrons (five Typhoon fighters and two F-35B stealth fighters). By comparison, during the 1991 Gulf War, the RAF fielded around 30 squadrons of combat aircraft. Modern jets are far more capable, yet mass still matters for maintaining continuous operations. The RAF’s fast jet fleet, combining Typhoons and F-35s, numbers roughly 150 aircraft (a portion of which are trainers or not combat-coded). This must cover homeland Quick Reaction Alert (intercepting Russian bombers that periodically probe UK and NATO airspace), deployments to defend NATO’s eastern flank (Britain regularly rotates Typhoons to the Baltics or Romania for air policing), and overseas expeditionary needs. The service also provides vital enablers like Airborne Early Warning (AEW) & control planes, air refuelling tankers, and transport aircraft. Some of these capabilities have seen cuts: the older E-3 Sentry radar planes were retired in 2021, leaving a gap until new Boeing E-7 Wedgetail AEW aircraft arrive around 2024/25, and the order was reduced from 5 to 3 aircraft to save money. Similarly, the RAF’s fleet of C-130J Hercules transports – workhorses for special forces and tactical airlift – was scrapped in 2023, with the larger A400M assumed to cover all airlift needs. The result is less flexibility, and the UK relying more on allies for niche air support.

On the positive side, RAF’s investment in drones and future combat air is notable. Britain has operated Reaper MQ-9 drones for surveillance/strike (mainly in the Middle East) and is now acquiring the more advanced Protector RG Mk1 (MQ-9B) uncrewed aircraft, with the first in service in 2024. These long-endurance drones will bolster both ISR – intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance – and strike options and the MoD has committed that at least 10% of its equipment procurement budget from 2025 onward will go to “uncrewed and autonomous systems and AI-enabled capabilities”. That reflects a drive to stay at the cutting edge of military technology – swarming drones, AI-driven decision support, and perhaps semi-autonomous combat aircraft are on the horizon. Britain is a lead nation, with Italy and Japan, on the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), which is developing a sixth-generation fighter jet by the mid-2030s – successor to Typhoon, often called “Tempest”. The IRR confirmed the ambition to make the RAF a world leader in “cutting-edge capabilities… vital to retain a decisive edge as threats rapidly evolve”. This includes not just the new fighter, but adjunct technologies like “loyal wingman” drones that would fly alongside piloted jets, advanced sensors, and artificial intelligence in command and control.

However, these future systems don’t solve immediate shortfalls. Right now, the RAF’s ability to sustain high-tempo operations, like an extended air war or enforcing a no-fly zone, is constrained by limited munitions stockpiles and a small pilot cadre. The UK has worked to address some of this – for example, it has joined a collaborative purchase of precision-guided missiles with other NATO members to economize and boost inventories. During the Libya intervention in 2011, the RAF famously ran low on-strike missiles; such lessons have prompted modest improvements. But the Ukraine conflict’s enormous consumption rates of missiles and bombs serve as a warning: Western air forces, including Britain’s, would need a massive surge in production to fight a major war. London has begun some steps, like funding the expansion of domestic missile maker MBDA’s capacity, but it remains a concern. In sum, the RAF’s quality is first-class, yet quantity and sustainment remain Achilles’ heels.

Plans to Modernise: Big Investments and New Capabilities

Faced with these gaps, the UK has announced a slate of investments and reforms across all services. The government’s Integrated Review (2021) and its Refresh (2023) set out a vision for a more modern, threat-focused force. Recent budgets – including emergency uplifts after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – have started to finance this “new chapter” in UK defence. Some of the key programs and changes, by service, include:

- Army – Transforming Mobility and Firepower: The British Army is undergoing its Future Soldier restructuring while awaiting new hardware. A pivotal project is the Boxer 8×8 wheeled armoured vehicle – at least 500 Boxers are on order to equip new Mechanised Infantry brigades, giving troops a highly mobile, well-protected personnel carrier (a stark improvement over lightly armoured trucks). The long-troubled AJAX reconnaissance vehicle project appears to be back on track after fixes; if fully delivered, AJAX will provide advanced sensors and firepower for armoured cavalry units, replacing 1970s-era Scimitar light tanks. The Challenger 3 tank upgrade will modernize the gun (switching to NATO-standard 120mm smoothbore) and electronics of the Challenger 2, with the first prototypes already built – the goal is to have a “fully regenerated” tank fleet by 2030. To fill the artillery gap, the Army rapidly procured 14 Archer self-propelled guns from Sweden, delivered in 2024, and it is exploring a larger purchase of a new artillery system under the Mobile Fires Program, potentially teaming with the U.S. or France on advanced howitzers or rockets. Britain is also investing in a long-range precision strike: it has ordered additional Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS) rockets, is part of a joint European program for a new deep strike missile, and is considering land-based anti-ship missiles to defend the littorals. Air defence is getting attention too: the Sky Sabre medium-range SAM (capable against aircraft and some missiles) entered service in 2022, and the MoD is looking at partnering with Italy and Japan on a next-generation ground-based air defence. Finally, a new Ranger Regiment was created as part of a special operations brigade to train and assist partners abroad (and presumably to free up elite units for higher-end tasks). Overall, the Army’s plan is to become leaner but more lethal: fewer infantry battalions, but each with better protection and digital connectivity; a focus on long-range fires and drones to “punch above weight.” The challenge will be timing – many of these new systems won’t fully arrive for several years, leaving a dangerous interim. A defence source warned in 2023 that current plans “deliver the transformation too slow to meet the heightened risk” after Ukraine. That is why Army leaders press for accelerated timetables.

- Royal Navy – Renewing the Fleet and Sustaining Nuclear Deterrence: The Navy is mid-way through a once-in-a-generation recapitalization. The two Queen Elizabeth-class carriers are now operational, with Prince of Wales returning to duty after repairs. The focus is on properly equipping them: that means steadily growing the F-35B Lightning force, the UK has purchased ~48 so far, with more on the way, and integrating them with allied jets – notably, U.S. Marine Corps F-35s have embarked on British carriers to help fill out air wings, a unique cooperation. The surface fleet renewal is anchored on the Type 26 frigates – eight ships designed for antisubmarine warfare to protect the deterrent and carriers. The first, HMS Glasgow, is fitting out, and others are under construction in Scotland. In parallel, five Type 31 frigates – to be called the Inspiration class, e.g. HMS Venturer – are being built as general-purpose frigates that are cheaper and can handle tasks like maritime security or Gulf patrols, freeing up high-end ships for frontline duties. The RN is also investing in support ships: new Fleet Solid Support ships were ordered to supply the carriers at sea, and an upgrade to the amphibious lift capability is in discussion – though one of the two Albion-class amphibious assault ships may be retired early to save money. Undersea, the big ticket is the Dreadnought-class ballistic missile submarines – four boats to replace the current Trident subs in the early 2030s, ensuring continuous at-sea nuclear deterrence through 2060. This project has been protected from cuts, it “is the MOD’s highest priority”, but its sheer scale – each sub displacing 17,000 tons, laden with new technology and American-supplied missile tubes – makes it a monster for the budget. The Astute-class nuclear attack subs program, 7 boats, is nearly complete – the latest HMS Agincourt will join by mid-decade. Looking ahead, the UK made a landmark deal with the U.S. and Australia under AUKUS to develop a new SSN-AUKUS attack submarine, which will incorporate British design and American technology, to be built for the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy in the late 2030s. While strategically significant, this means Britain is committing now to yet another expensive submarine class development. To avoid gaps, the lifespan of some current Astutes may need an extension. The Navy also aims to embrace unmanned systems: it has trials of robotic submarines for surveillance, unmanned surface vessels for tasks like minesweeping, and is working on integrating drones with ships (for recon and targeting). The maritime drone budget is part of that 10% uncrewed systems pledge. In summary, if fully realized, the RN of the 2030s will have: two carrier groups, a robust escort fleet of ~24 frigates/destroyers, and modern subs – a powerful force. But getting there requires navigating budget shortfalls and ensuring skilled manpower, the Navy has struggled to crew all its high-tech ships; retention of engineers is an issue. In the near term, the RN has upped its presence in the North Atlantic and High North alongside NATO allies, responding to increased Russian naval activity. British P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft and Type 23/Type 45 ships have played cat-and-mouse with Russian subs around UK waters, even as Russia’s navy rehearsed aggressive moves – such as Russian bombers flying down the Norwegian Sea and along the UK coast in mock attack runs. These incidents drive home the importance of anti-submarine and air defence capabilities that the RN’s new investments aim to bolster.

- Royal Air Force – Building the Future Air Combat System: The RAF’s modernization revolves around a two-track approach: incrementally upgrade existing forces (Typhoon, F-35, enablers) while heavily investing in the next-generation systems. On the first track, Typhoon fighters are being fitted with e-scan AESA radars and new weapons. The UK developed the Meteor beyond-visual-range air-to-air missile, one of the world’s best, now fielded on Typhoons, and the SPEAR family of air-to-ground missiles. The life of Typhoons will extend into the 2030s to ensure a capable fleet until a replacement arrives. Meanwhile, more F-35B Lightnings will join 617 and 207 Squadrons; these stealth jets give the UK cutting-edge strike and intelligence abilities, particularly when operating from carriers or austere bases. The RAF has also prioritized strengthening its support assets: it brought in the Poseidon P-8A maritime patrol aircraft (vital for sub-hunting, filling a gap left since 2010), and is standing up three RC-135 Rivet Joint signals-intelligence planes for electronic surveillance. The looming arrival of the Wedgetail E-7 AEW&C planes will greatly improve air battlespace awareness. Additionally, the RAF leads the UK’s military space efforts – it created the UK Space Command in 2021 and is investing in satellite communications and surveillance, recognizing space as a contested domain. On the second, more transformative track, the Global Combat Air Programme (Tempest) is the jewel: a sixth-gen fighter with stealth, drone control capability, and advanced propulsion. The IRR confirmed a commitment to this program even as it acknowledged that simply “standing still” – i.e. maintaining current capabilities against rising threats – likely requires an extra £6 billion per year in defence spending. Britain has roped in international partners to share Tempest costs and know-how (Italy and Japan formally joined, forming GCAP), aiming for a flyable demonstrator by 2027 and entry into service by the mid-2030s. Simultaneously, the RAF’s Project Mosquito explored a prototype “loyal wingman” drone to fly alongside fighters; though that specific project was shelved, the RAF is pushing the concept forward with the goal of fielding combat drones that can scout or even strike in coordination with manned jets. The MoD’s requirement that at least 10% of procurement funds go to unmanned and AI highlights this shift. We may see the RAF acquire “swarming” munitions, drones that overwhelm air defences, and more advanced UAVs for electronic warfare and resupply roles. Another area of investment is airbase resilience and logistics – after watching Russian missiles target Ukrainian airfields, the RAF is improving the hardening of its bases and exploring dispersal strategies (using civilian runways or austere sites in wartime). It is also updating its refuelling and transport fleet (e.g., buying more A330 Voyager tankers jointly with allies perhaps). In short, the RAF’s trajectory is to remain a high-tech force multiplier in NATO. The risk, as always, is funding: these programs are expensive and mostly long-term. If budgets fall short or inflation eats away at them, the RAF could face a modernization bow wave it can’t afford. But as of now, the political declaration is that the UK will “accelerate the adoption of cutting-edge capabilities… vital to retain a decisive edge” and simultaneously “reverse the hollowing out of recent decades” by rebuilding stockpiles and enablers.

The War in Ukraine: Catalyst, Stress Test, and the Question of Sustainment

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has been the single biggest spur to Britain’s defence reawakening. The shock of full-scale war in Europe pushed UK leaders to make hard choices that had been deferred. Almost immediately, Britain emerged as a leading supporter of Ukraine, second only to the United States in military aid among Western nations. This was in line with the UK’s self-image as a resolute defender of the international order – and as a country willing to take risks where others hesitate. London set the tone early, shipping thousands of Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapons (NLAWs) to Ukraine even before the war began, which proved crucial in halting Russian armoured columns around Kyiv. Since then, the UK has provided a wide array of arms: anti-air missiles (Starstreak MANPADS), hundreds of drones, artillery guns and MLRS rocket systems, armoured vehicles, vast quantities of ammunition, and training for tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops on British soil. In a notable escalation, Britain in January 2023 became the first country to pledge Western main battle tanks to Ukraine (14 Challenger 2s) – a move intended to galvanize others to follow. Indeed, after the UK’s announcement, Germany and the U.S. agreed to send their Leopard 2 and Abrams tanks, breaking a logjam in allied support.

For the UK, this staunch support serves both moral and strategic ends. Officials argue that helping Ukraine fight off Russia now will prevent a larger war involving NATO later. As General Sanders said, ensuring Putin’s defeat in Ukraine “makes us safer” and is a cause for which giving up some British capabilities is worthwhile. However, this assistance has come at a cost to British readiness. The transfer of those 14 Challenger 2 tanks, plus 30 AS90 self-propelled guns and 100+ armoured vehicles, “will leave us temporarily weaker”, Sanders admitted plainly. There is irony in the UK having to re-arm itself because it generously armed someone else – a dynamic reminiscent of Lend-Lease in WWII, when Britain supplied arms to allies at the expense of its own stocks. By 2023, the Army had to request emergency purchases (like the Archer guns) to plug holes left by donations to Ukraine. Also, with the expenditure of advanced missiles, the UK gave Ukraine many Brimstone precision missiles and Starstreak anti-air missiles, which means British inventories need urgent replenishment. The MoD did place orders – for example, a £229 million deal for “thousands” of new anti-tank weapons to restock after NLAW donations – but ramping up production takes time. Factories that had gone partially idle in the 2010s must now work 24/7 to meet demand.

This raises the issue of sustainability. If the war in Ukraine continues at high intensity, can Britain (and its NATO allies) continue supplying munitions without undermining their own war reserves? Defence economists note that many Western countries have not maintained Cold War-level production capacity. The UK, for instance, has one facility assembling complex missiles (MBDA’s Lostock plant) and a few filling artillery shells. To avoid running dry, Britain is coordinating with NATO and EU initiatives to jointly procure ammunition – essentially pooling orders so the industry has the confidence to invest in expanding output. The government has acknowledged that stockpiles of “munitions and enablers” had been depleted by years focused on small wars and needed rebuilding. Part of the new money in 2023–25 is earmarked for precisely that: buying ammunition, spare parts, and mobility assets at scale. Defence Secretary (at the time) Ben Wallace frequently highlighted that a lesson of Ukraine is the absolute necessity of war stock logistics – you need mountains of supplies to sustain modern combat.

Politically, the UK’s unwavering support for Ukraine has bolstered its transatlantic and European standing. It showed that even outside the EU, Britain is a key player in European security. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s visits to Kyiv in 2022 were symbolically powerful. Under PM Sunak (and now under PM Starmer, assuming a change by 2025 in this scenario), the UK has kept that commitment. British instructors have trained Ukrainian recruits in England, and Britain helped form the “International Fund for Ukraine” with allies to provide ongoing lethal and non-lethal aid. All parties in Westminster broadly agree on backing Ukraine, though funding it long-term will require budgetary planning. Notably, the UK has had to absorb inflation in its defence budget while diverting funds to Ukraine aid – a double strain. In 2022–2023, UK defence spending including support to Ukraine reached about 2.3% of GDP. There is some debate if that can be sustained, especially if U.S. support becomes uncertain.

And that is the big strategic question: what if American commitment falters? In the U.S., some politicians have signalled wavering resolve on unlimited Ukraine aid. A future U.S. administration (for example, one led by Donald Trump or like-minded figures) might reduce support or push Europe to shoulder an even larger burden. British officials are keenly aware of this possibility. The UK’s leadership in the Ukraine effort can be seen partly as an attempt to stiffen European resolve to act even “regardless of the U.S. attitude” swings. London has quietly positioned itself as the coordinator of a European/northern European support coalition – for instance, the UK led the “International Tank Fund” for Ukraine and coordinated a coalition to send advanced storm-shadow cruise missiles. If Washington dialled down, Britain would almost certainly lobby EU/NATO states to step up further. However, could Europe (even with the UK and France) replace U.S. capabilities in Ukraine? Likely not fully, given U.S. heavy weapons contributions and intelligence assets. So the hope in London is to keep the Americans sufficiently engaged, while Europe increases its share to reduce the burden on any one actor.

There’s also the matter of public and fiscal support at home. Thus far, UK public opinion has strongly favoured helping Ukraine, seeing it as a fight for democracy in Europe. But as the war drags on and economic pressures mount, any government will have to justify the costs. The British military establishment’s argument is that aiding Ukraine is the “front line of our own security” – stopping Putin in Donbas so British troops don’t have to fight him elsewhere. That logic, akin to Cold War-era forward defence, has traction but could be tested if the war goes on for years. The government’s recently increased defence budget was explicitly tied to the Ukraine-driven threat: Sunak announced in early 2023 an extra £5 billion over two years, partly to replenish ammunition stocks and fund the next generation of nuclear subs. In other words, Ukraine is cited as the reason to spend more on defence – a narrative that aligns strategic necessity with domestic politics.

In sum, the Ukraine war has been a catalyst for Britain’s rearmament and a stress test that exposed where Britain had become too fragile. It prompted immediate action – supplying weapons, upping readiness of certain units, revising strategic assumptions – and sped up longer-term decisions, like raising budget targets. But it also raises the stakes: Britain must now recapitalize its forces quickly to both continue aiding Ukraine and ensure it could meet a direct contingency if one arose. The war galvanized NATO’s most significant strengthening in decades – and Britain wants to remain at the forefront of that, but it will require money and political will even after headlines about Ukraine fade.

NATO, Europe and the U.S.: A New Defence Equation

Britain’s rearmament is taking place in a broader context of shifting responsibilities within the NATO alliance and Europe. The war in Ukraine has, paradoxically, reinvigorated NATO – but it’s also underscored Europe’s heavy dependence on the United States and the need for Europeans to carry more of the load. As one European security project noted, Europe’s pursuit of collective security is evolving as it “reduces reliance on external powers”. The UK, though no longer in the EU, remains a critical part of Europe’s defence architecture. British leaders frequently emphasize NATO unity while also encouraging European allies to boost their capabilities.

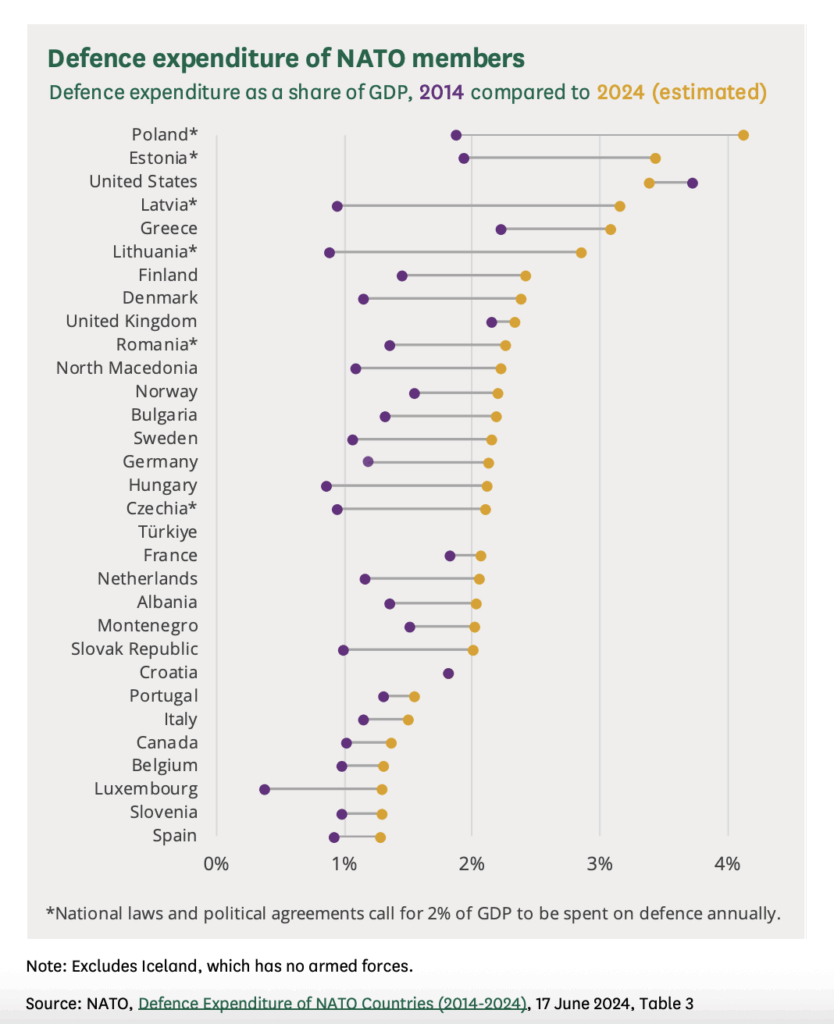

The numbers tell the story: European NATO members have sharply increased defence spending since 2022. The EU Council reports that between 2021 and 2024, EU member states’ total defence expenditure rose by over 30%, reaching €326 billion (≈1.9% of EU GDP) in 2024. This is a significant jump after years of meagre growth. Germany’s famous “Zeitenwende” pledge of an extra €100 billion for the Bundeswehr is one example; France has upped its budget to record levels; Poland is surging toward 4% of GDP on defence with massive arms buys. According to NATO data, the European allies and Canada together went from spending on average 1.66% of GDP in 2022 to about 2.02% by 2024. Still, the U.S. alone accounts for roughly 70% of NATO’s overall military expenditure. That imbalance, long criticized by American presidents, is something Europe is striving to correct, albeit gradually.

Britain sees itself as a bridge – both a European power and a close U.S. ally. In practical terms, the UK often serves as the leader of Europe’s high-end military efforts within NATO. It is one of only two nuclear powers in NATO Europe (France being the other). It has one of the few deployable carrier strike groups, one of the largest defence budgets in Europe, and highly capable special forces and intelligence services. All this means London has outsized influence on NATO policy relative to its size. For instance, the UK was instrumental in pushing NATO to enhance its eastern flank posture after 2014; it led a multinational battlegroup in Estonia as part of NATO’s Forward Presence, and post-2022 it doubled its troop presence there to brigade level on rotation. The UK also announced it would “meet strength with strength from the outset” if NATO territory is threatened, signalling a shift to a more muscular forward defence – a stance General Sanders echoed when he said Britain and NATO must be unequivocally prepared for conflict to deter Russia.

However, the elephant in the room is the future of U.S. commitment. As the Carnegie Endowment assessed, if a future Washington “made Donald Trump’s threats to reduce America’s commitment to European defence a reality”, NATO would be weakened and the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force might have to assume a larger warfighting role – but “fighting such wars… would require far more resources than the JEF currently has.” In plainer terms, without the U.S., European defence would need a massive upgrade. British planners tacitly acknowledge this. It’s one reason the UK is pushing for NATO members to adopt not just the 2% of GDP spending minimum, but also a new target: at the July 2023 Vilnius summit, NATO agreed each ally should spend at least 2% and aim higher. In fact, at the 2025 NATO summit allies made a 5% commitment – not 5% of GDP total, but 5% of GDP specifically on investment in new equipment and R&D, to ensure the money goes into improving capabilities. The UK has supported these moves and itself set an “aspiration” for 2.5% of GDP on defence in the longer term, as well as backing the idea that some NATO-European combination must be able to act if the U.S. is less engaged.

European strategic autonomy, a buzzword in EU circles, often advocated by France’s President Macron, envisions Europe taking more independent action. The UK, while outside the EU, has shown openness to cooperating in European frameworks post-Brexit in the security realm. For example, Britain recently agreed to rejoin the EU’s Military Mobility project, to expedite the movement of forces across Europe. Also, the UK and EU penned a new declaration in 2023 to enhance cooperation on defence industrial supply chains. All this suggests that in the face of Russian aggression, geopolitical realities are trumping past Brexit rancour – the focus is on collective strength.

From Britain’s perspective, NATO remains the cornerstone, but complementary initiatives are welcome if they bolster capabilities. The UK has a foot in multiple camps: NATO, the U.S.-led AUKUS pact in the Indo-Pacific, and European-led groups like the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) and the French-UK Combined Joint Expeditionary Force. This multi-layered approach is by design. It gives the UK flexibility to act with different coalitions. But it also means Britain must carefully manage resources – it can’t be strong everywhere at once with a finite budget. Some critics have warned that pursuing global deployments (e.g., focusing on the Indo-Pacific to support the U.S. in checking China via AUKUS or sending the Carrier Strike Group to Asian waters) might dilute focus from the pressing needs in Europe’s neighbourhood. The Integrated Review tried to square this by calling Britain “a European country with global interests” – hence it will tilt to the Indo-Pacific somewhat but not at the expense of NATO obligations.

Notably, UK defence spending plans have assumed a significant increase to reach 2.5% GDP by mid-decade. The Commons Defence Committee warned that without a clear path to 2.5%, the MoD would have to make painful cuts or delays to afford even the replenishment of munitions given to Ukraine. Such a path was laid out by early 2025: Prime Minister Keir Starmer, as assumed in this timeline, announced that starting in 2027, Britain will spend 2.5% of GDP on defence for the remainder of that Parliament. To fund this, an unpopular but telling decision was made – reducing the international aid budget from 0.5% to 0.3% GNI, redirecting that money to defence. This underscores how priorities have shifted: security is taking precedence. Starmer even floated an ambition for 3% of GDP on defence in the next decade, “subject to economic and fiscal conditions”. Of course, aspirations are not guarantees. The UK’s fiscal health is under strain, and other needs (like healthcare, as always) compete for funds. But the bipartisan consensus on at least modestly higher defence spending appears solid for now – largely thanks to the awareness of the Russian threat. It’s also about sending a signal: as one former defence chief said, focusing narrowly on “2.5% or 3%” misses the point if it doesn’t translate to real military power. Yet symbolically, it “signals to our allies and adversaries” Britain’s intent – failing to follow through “gives the wrong signal”, as a former minister put it.

One ally closely watching is the United States. Washington has for years cajoled Europeans to invest more in their militaries. Under President Biden, the tone is friendlier than under Trump, but the message is similar. The UK increasing its budget and leading by example gives London more clout in transatlantic talks. If Britain were perceived as freeloading or in decline, its special relationship influence could wane. Instead, British defence officials frequently highlight that “last year, the UK was the third biggest defence spender in the world” (after the U.S. and China) – a statistic that includes one-time boosts, but nonetheless Britain wants to be seen as pulling its weight. The NATO Secretary General and U.S. Defense Secretary have both praised UK contributions to NATO – e.g. the UK’s framework nation role in Estonia, and its leadership in new capabilities like carrier strike and fifth-gen air integration. But they also privately worry about the burnout of British forces if not re-equipped. The leaked U.S. general’s comment that the UK is “barely tier two” shows an undercurrent of concern in Washington. Britain’s response – promises of new investment – is aimed partly at assuaging the U.S. that the UK will remain a first-rank ally.

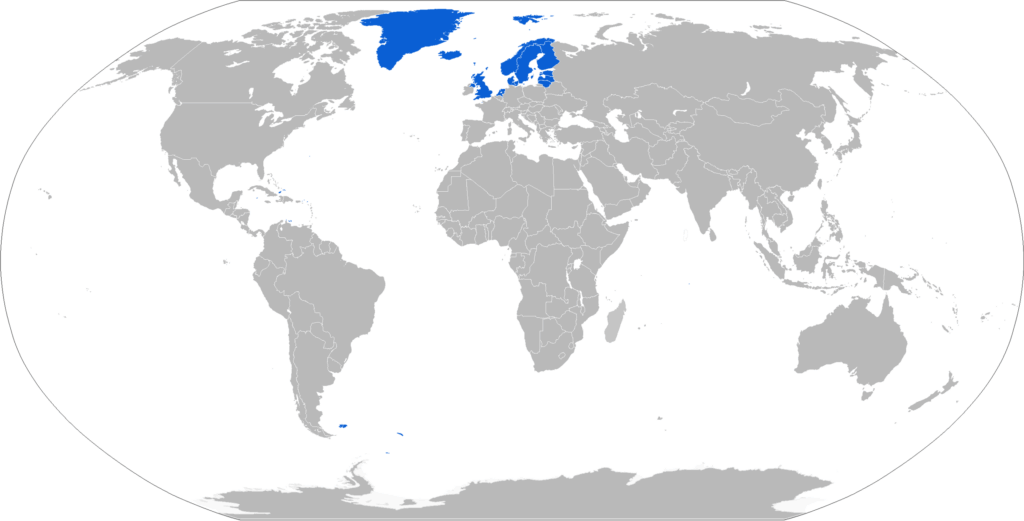

Lastly, Britain’s role in regional European mini-lateral groups merits attention. The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), a UK-led coalition of 10 Northern European nations (Nordic, Baltic, plus the Netherlands), has become a notable framework for security cooperation outside of NATO’s formal structures. It includes originally non-NATO Finland and Sweden (until they decided to join NATO), and its focus is on the High North, North Atlantic and Baltic Sea security. The JEF has held drills and could respond to grey-zone aggression or crises below NATO’s Article 5 threshold. We now examine JEF and Britain’s Nordic-Baltic security guarantees in detail.

The Joint Expeditionary Force and Nordic-Baltic Security: British Guarantees on Trial

The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) is an interesting test of Britain’s ability to provide security leadership in Europe, especially in Northern Europe. Launched in 2014–2015, the JEF brings together the UK with Norway, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Iceland – essentially a coalition of like-minded, mostly Nordic-Baltic states, “a coalition of the willing” rather than a formal alliance. Its original rationale was to plug a gap: it could act as a nimble grouping to address crises where NATO might be slow to react or where Article 5 isn’t invoked – for example, hybrid warfare scenarios, cyber-attacks, or limited incidents. The JEF achieved full operating capability in 2018 and since then has focused on Baltic Sea security through frequent exercises and information-sharing. British commanders serve as the core, the UK provides the standing headquarters and lead elements, with other nations contributing forces as needed. Notably, JEF is not under NATO command, though it’s complimentary to NATO. It’s flexible: if any two member countries agree to undertake an action (say, a humanitarian response or a deterrence exercise), they can invoke the JEF framework and invite others to join. This allows quick coalitions to form under UK leadership.

The war in Ukraine has, if anything, increased JEF’s importance as a political signal. In February 2022, just before the invasion, JEF defence ministers met and coordinated moves to support Baltic security. In late 2022 and 2023, JEF nations convened for high-level meetings – e.g., a leaders’ summit in Riga – to discuss regional defence and even Ukraine assistance. JEF has done exercises in Scandinavia, including an amphibious drill simulating the retaking of an island. These activities demonstrate resolve to Russia that Northern Europe is united. However, with Finland and Sweden now in NATO, some questioned if JEF was still needed. A Carnegie Europe analysis bluntly noted that “if the JEF did not exist, it might not be necessary to invent it” given NATO’s renewed focus on the region – but since it does exist and members value it, it should be given realistic tasks and resources to contribute to deterrence in the Nordic-Baltic area. In other words, JEF should be a useful adjunct to NATO, not a distraction or redundant layer.

From the perspective of the smaller countries – Baltic states and Nordics – British involvement is a valuable extra assurance. Before Finland and Sweden got on the path to NATO, the UK offered something concrete: in May 2022, then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson signed mutual security declarations with Sweden and Finland, pledging UK support if either came under attack. These were not NATO Article 5 guarantees, but politically weighty commitments. “The British commitment was of high value at a time of great tension,” said Anna Wieslander of the Atlantic Council, noting it went further than what any other NATO country had offered bilaterally. Johnson’s written assurances promised that Britain would come to Sweden/Finland’s aid, potentially with military means, during the vulnerable period while their NATO memberships were pending ratification. Swedish and Finnish officials welcomed this as an “extra layer of assurance” – Johnson was quite specific about deploying British air force, army and naval assets if needed. It also carried a symbolic punch: “It sends a signal to Russia that a nuclear power is willing to do this,” Wieslander noted. In effect, the UK declared itself ready to act as a guarantor for those nations even before NATO could. This bold move helped nudge them over the line into NATO and demonstrated British commitment to Nordic-Baltic defence.

Now that Finland and Sweden are in NATO, those particular bilateral guarantees may never be explicitly tested. But the ethos behind them remains relevant. The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) have long viewed the UK as a patron of their security second only to the U.S. Britain leads the NATO battlegroup in Estonia, as mentioned, and has reinforced it with extra troops, especially since 2022. Baltic officials often praise the UK for having troops on the ground continuously since 2017, showing deterrence credibility. Through JEF, these countries get additional joint training and rapid consultation ability with the UK.

However, the question arises: Are British security guarantees actually valid and credible, given the UK’s own force shortfalls? For deterrence to work, London’s promises must be backed by the ability to deliver. The concern is that if the UK’s forces are overstretched or under-strength, then its “insurance policy” to others might ring hollow. For example, if a crisis erupted in the Baltic, could Britain rapidly send a brigade or air squadrons in support? Currently, the British Army would struggle to mobilize a brigade with full heavy equipment in short order. The RAF would certainly send fighters, indeed it has quick reaction plans for that, but sustaining a long air campaign on the eastern edge of Europe would be challenging without U.S. logistics. The Royal Navy could deploy a few warships to the Baltic, but it would then leave other areas thinly covered. These limitations don’t invalidate the guarantees – they just mean the UK would likely lean on NATO and the U.S. to bolster any bilateral action.

The British government is keenly aware of this perception issue. Hence the emphasis on improving readiness and meeting NATO commitments under new plans. One defence source insisted that “the US and the rest of NATO understand the UK is planning to rebuild its force… [it] is now in a better cycle with a lot of new investment over the next ten years”, pushing back on the idea Britain isn’t reliable. Indeed, the UK has started pre-positioning some equipment in Germany, to speed reinforcement of the East, and is investing in better lift capability.

For the JEF specifically, analysts like Ian Bond (author of the Carnegie piece) recommend that it focus on what it can do well: the grey zone and hybrid threats. This could mean JEF nations jointly countering a cyber-attack on Baltic infrastructure or sending a combined naval patrol to stop Russian interference with undersea cables or pipelines in the North Sea. JEF could also be a framework for forward deployments short of war – e.g., if Baltic states felt threatened, a quick JEF exercise on their soil could show presence even if NATO was still deliberating. That Carnegie study concluded that since JEF members “seem keen to preserve the format,” they should “ensure JEF has realistic tasks, is resourced to perform them, and contributes to NATO’s deterrent and defensive activities in the Nordic-Baltic and North Atlantic” regions. In practice, that means Britain must allocate some resources to JEF exercises (which it has – HMS Queen Elizabeth led a JEF maritime group in the Baltic in 2023, for instance). It also means keeping political focus: the new UK government in 2025 has signalled continued commitment by scheduling a JEF leaders’ summit in London to reinforce momentum.

One scenario that haunts planners is a future U.S. retreat from Europe (even partially). In that case, could something like JEF or a European coalition fill the breach? Possibly, but it “would require far more resources than the JEF currently has” to fight a full-scale war on its own. JEF was not designed to be Europe’s Article 5 alternative: it’s a supplementary tool. If NATO’s centre of gravity changes, the UK might push to strengthen JEF into a more integrated force. But that would entail European nations committing troops to British-led formations more permanently – a complex political sell. More likely, the UK would try to work with France and Germany on a broader European framework, perhaps an EU-NATO hybrid.

Meanwhile, Britain also engages Nordic security via other means: the UK has a close alliance with Norway – focusing on the Arctic/High North, where UK Royal Marines train in Norway annually for cold-weather warfare. It cooperates with Denmark on Arctic and North Atlantic surveillance. With France, the UK has the Lancaster House treaties that created a Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF) able to deploy a Franco-British division or carrier group together. These overlapping arrangements give the UK avenues to support northern and eastern Europe even if one mechanism faltered.

In essence, Britain’s web of security commitments – formal NATO obligations, JEF political commitments, and bilateral pledges – is part of its strategy to embed itself as Europe’s defence leader. But to truly be that, Britain must have the capabilities to back it up. Hence the urgency to rearm: the credibility of UK guarantees to others depends on the credibility of its armed forces. The UK-led JEF, for example, will only deter aggression if the UK (and its partners) can rapidly deploy meaningful force. That is why British defence discourse now stresses both “high readiness” and “high capability”. The goal is that any potential foe, such as Russia, calculates that meddling in the Baltic or North Sea would immediately trigger a professional, well-armed multinational JEF/NATO response, including robust British forces – not an under-strength token force. One concrete step in that direction: the UK has pre-assigned a brigade to the defence of Estonia/Latvia under NATO plans and is expanding munitions stockpiles in those countries. It also signed a new agreement in 2023 under which British and Norwegian air forces will jointly police each other’s airspace if needed – a force multiplier for northern skies. These moves shore up the “insurance” that Britain offers. They signal that Britain’s security guarantees, such as to the Nordic-Baltic region, are backed by tangible deployments and political will. Of course, sceptics will point out that Britain’s own defence cuts of the 2010s undermined that credibility in the first place. Restoring it is a work in progress.

Prospects for Britain’s Re-Arming

American and European divisions, essentially forming combined formations. This is a force multiplier but also a necessity given its limited size – in a major conflict, the UK would almost certainly fight as part of a coalition, not alone.

The defence industrial base in Britain will be under pressure to deliver. Big programs like Dreadnought subs, Tempest fighters, Type 26 frigates, etc., are all scheduled to peak in the late 2020s to mid-2030s. The industry will need enough skilled workers and steady orders to avoid delays. One positive is that defence is politically seen as a sector for high-tech jobs and levelling up regions – shipyards in Scotland and England’s north, aerospace in Lancashire, etc. So, there’s cross-party support for spending that simultaneously boosts the UK industry. But as seen with nuclear projects, reliance on a few suppliers can be problematic. The MoD is trying to broaden its supplier base and encourage innovation (start-ups in drones, space, AI). Success here could both make rearmament more affordable and spur the “global Britain” technology ambitions.

Strategically, Britain will need to continue navigating its dual role: defending Europe and pursuing global influence. The Integrated Review Refresh (March 2023) put it starkly: “We have a wartime prime minister and a wartime chancellor… History will look at the choices they make in the coming weeks as fundamental to whether this government genuinely believes its primary duty is the defence of the realm”. Those words were aimed at spurring immediate budget action. Going forward, similar resolve will be needed beyond the Ukraine crisis. Will Britons support higher defence outlays if, say, the Russia threat diminishes for a time? The comparison to the 1930s suggests constant vigilance is required; Britain doesn’t want another cycle of “bust and boom” in defence where a few years of calm lead to complacency.

One encouraging development is the extent of consensus that has formed. In the UK Parliament, the need to rebuild the military has broad agreement – the debate is mostly about how Britain’s renewed drive to strengthen its military is now underway, but it faces significant challenges ahead. Funding, though rising, must contend with inflation and competing domestic needs. As of 2025, defence spending stands at around £54 billion (2.2% of GDP), and plans envisage it climbing to perhaps £70 billion by 2027 to hit the 2.5% target, depending on economic growth. That will require sustained political commitment through multiple budget cycles – not just headlines about reaching a percentage. The Public Accounts Committee’s rebuke that the MoD was banking on money that wasn’t secured yet serves as a warning. The new government will have to allocate those funds in reality, likely meaning tough choices such as cutting other expenditures or raising some taxes. The broader economic picture, with Britain experiencing sluggish growth and high debt, means defence might still face an uphill battle in the treasury if crises abate.

Another challenge is managing procurement effectively. Throwing money at the MoD without reform could see repeats of fiascos like the Ajax vehicle or cost overruns swallowing capability. There is pressure to simplify and speed up acquisition – the MoD has started using more “urgent operational requirements” processes (like the swift Archer Howitzer buy) to get kit faster, bypassing some bureaucracy. The war in Ukraine taught that peacetime procurement rules can be a hindrance when weapons are needed quickly. Defence sources urged easing these rules to allow rapid purchase of weapons and ammo. If Britain truly believes it’s in a “wartime” situation strategically (even without direct conflict), it may adopt a quasi-wartime procurement tempo. This could mean more off-the-shelf purchases from allies or leveraging collaborative buys – for instance, the UK joining a German-led effort to procure air defence systems. Success in rearming will partly depend on overcoming the MoD’s historically risk-averse culture in buying equipment.

Manpower is also a concern. The modern kit is of little use without skilled personnel to operate it. The Army’s recruiting woes, the RAF’s pilot shortage, and the Navy’s specialist retention problems all need addressing. Plans to trim Army end-strength might be revisited – indeed, in light of Ukraine, some in Parliament called to halt the cut in Army troop numbers. The government so far has stuck to the reduction (arguing advanced drones and cyber forces offset it), but if threat perceptions worsen, it could politically reverse that decision. Training is being enhanced – e.g., regenerating skills like air defence and electronic warfare that atrophied. The British military is also adjusting concepts: it’s emphasising dispersal, resilience, and interoperability with allies. For example, British Army units will train to seamlessly integrate with fast and what to prioritize, not whether to do it. The shadow defence secretary (when in opposition) backed the 2.5% goal and emphasized stockpiles and readiness, aligning with the government’s trajectory. Think tanks from across the spectrum, like the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and the more hawkish Council on Geostrategy, are producing analyses on fixing the fundamentals. Matthew Savill of RUSI argued that alongside sexy investments in AI and drones, “the foundations of defence must be fixed in ways which are fundamental, if unflashy” – such as rebuilding logistics, maintenance, and industrial capacity. He noted that just maintaining existing forces in the face of inflation and wear and tear likely needs billions more per year. This kind of expert input is influencing MoD planning. For instance, additional funds in 2023 were directed to improve accommodation for troops and upgrade training areas (boring but necessary), on top of buying armaments. The Army is reviewing lessons from Ukraine to update its doctrines around dispersal and the massive use of artillery and drones.

In external terms, Britain’s steps are being watched by allies. The Baltic and Nordic states, Poland, and others who rely on UK leadership are likely relieved to see Britain boosting defence – a credible UK is integral to their security calculus. France, which sometimes competes with the UK for the mantle of Europe’s leading military power, will also measure its efforts in relation. France is raising its defence budget markedly for 2024–2030. A bit of friendly competition here can benefit NATO overall. The United States, ultimately, will judge allies by whether they can defend their regions with less American help. If by the late 2020s, Britain has larger, better-equipped forces and European partners have improved, the transatlantic alliance will be more balanced. This could reassure a future U.S. administration that supporting NATO is not a one-sided affair, thus keeping the U.S. engaged – ironically, European autonomy and U.S. commitment are two sides of the same coin.