China has dramatically tightened its grip on global technology supply chains by extending export controls on rare earths, adding five more elements to its list and imposing new licence requirements on semiconductor users, just weeks before Presidents Trump and Xi meet. Beijing dominates the sector, accounting for about 70 % of global mining and roughly 90 % of rare-earth processing, and these minerals are essential for electric vehicles, aircraft engines and military radars. Under the expanded rules, foreign companies that use Chinese‑origin minerals or equipment must obtain export permits even if no Chinese firm is involved in the transaction.

Rare earth elements (REEs) are the unsung heroes of modern military and high-tech industries. These 17 metallic elements – from neodymium and dysprosium to scandium and yttrium – are critical for a host of advanced applications. They form key ingredients in precision-guided munitions, jet engines, satellite communications, and stealth technologies. For example, an F‑35 fighter jet, an Abrams tank, or a Patriot missile system cannot be built or operated without specialised rare earth magnets, alloys and components. In fact, REEs are used in everything from the powerful magnets in aircraft actuators and missile guidance systems to the sensors, lasers and radar of advanced military platforms. Without a secure supply of rare earths, NATO’s technological edge and operational readiness could be at risk

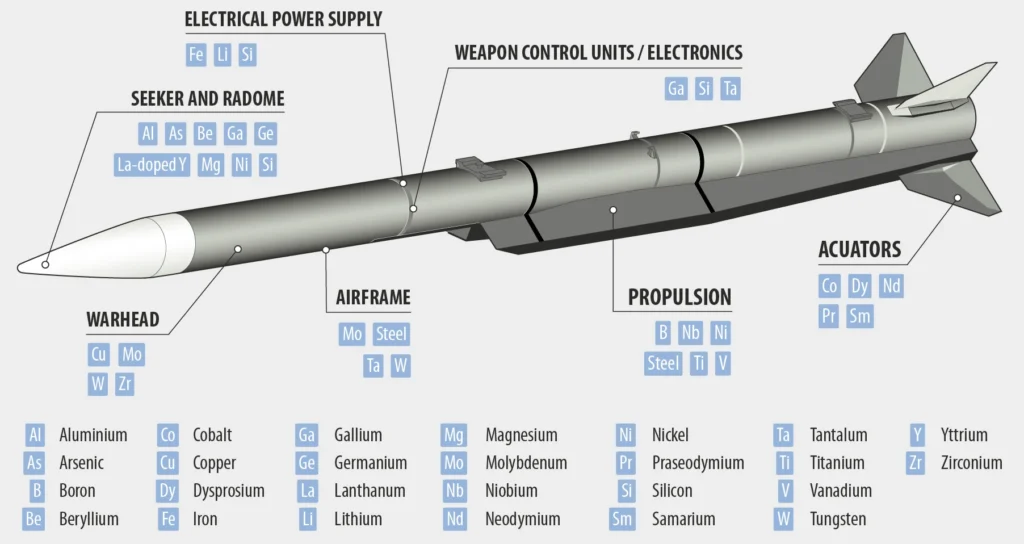

Tanks and Missiles Rely on Critical Materials

Modern NATO tanks and other military systems rely on a wide range of critical minerals. Rare earth elements like neodymium and dysprosium are used in sensors and targeting radar, while metals such as beryllium and titanium strengthen structural components. The diagram by IISS (above) illustrates how various materials – from advanced alloys to REEs – are integrated into a missile’s warhead, propulsion, control units and acuators. If the supply of any of these inputs is disrupted, it can seriously hinder the production or maintenance of military hardware.

China’s Dominance is Overwhelming

The strategic challenge arises from the fact that China overwhelmingly dominates global rare earths supply chains. China currently mines about 70% of the world’s rare earth ores and performs roughly 90% of the complex chemical processing that separates these elements into usable form. Even when rare earth ores are mined elsewhere – in the United States, Australia or Myanmar, for instance – they often end up being sent to China for refining and magnet manufacturing. Mining gives you the rock, but processing gives you the power. Beijing has spent decades building this near-monopoly, aided by cheaper costs, lax environmental standards and aggressive industrial strategy, while Western producers shuttered mines and plants as a cost-saving measure.

China has never been shy to wield this dominance as geopolitical leverage. A notable precedent came in 2010, when an unofficial Chinese embargo on rare earth exports to Japan, amid a diplomatic row, sent shockwaves through high-tech industries. Fast forward to 2025, and Beijing is formalising its grip: it recently announced its most stringent export controls yet on rare earth materials and magnets. Under new rules, Announcement No. 61 of 2025, any company anywhere in the world must obtain Chinese government approval to export products containing even trace amounts of Chinese-origin rare earths. This even applies if the item was produced using Chinese mining, processing or magnet-making technology, effectively a Chinese version of the U.S. “foreign direct product rule” that extends jurisdiction beyond its borders. In short, if Chinese rare earths or know-how appear anywhere in the supply chain, Beijing claims the right to block the final product’s export.

China’s new policy explicitly targets military end-users. Starting 1 December 2025, companies with any affiliation to foreign militaries – including those of NATO countries – will be denied export licences for rare earth materials or magnets. Any request to use rare earths for defence purposes will be automatically rejected, according to China’s Ministry of Commerce. Beijing has also added five more rare earth metals to its export restriction list (holmium, erbium, thulium, europium, ytterbium), bringing the total to 12 of the 17 rare earths now under Chinese export control. Even equipment for manufacturing other critical technologies is affected – for instance, China is imposing controls on certain machinery used to produce electric vehicle batteries. Chinese officials claim these measures are about national security and “international peace”: they accuse foreign actors of using Chinese-origin rare earths for military applications in ways that threaten China’s interests. But strategists see a clear signal that Beijing is prepared to weaponise its dominance of critical minerals in retaliation for Western semiconductor sanctions. Coming just weeks before a high-stakes U.S.-China summit, the timing suggests China is bolstering its negotiating leverage. As one analyst noted, “this helps with increasing leverage for Beijing” ahead of the anticipated Trump–Xi meeting. In effect, China is reminding the West that if pushed, it can choke off vital inputs to everything from smartphones to Joint Strike Fighters.

NATO’s Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

For NATO countries, these developments ring loud alarm bells. The United States and European allies have built their defence industrial base on the assumption of continuous access to advanced materials – an assumption now in question. The United States sources around 70% of its rare earth imports from China, and even that understates the dependency: nearly all the processing of rare earth ores from the lone U.S. mine in California is done in China. A U.S. Congressional analysis noted that the Pentagon relies on Chinese rare earths for critical components of jets and missiles. As a result, the People’s Liberation Army’s influence over rare earth supply “means even more difficult times both for the Pentagon and for a wide range of commercial manufacturers,” warned one American mining executive. The new Chinese export curbs only deepen these vulnerabilities, potentially widening the capability gap between China and the West by constraining Western weapons production. NATO’s most advanced militaries could find themselves hamstrung by shortages of tiny but crucial components – a classic case of the proverbial “for want of a nail, the kingdom was lost.”

European NATO members are equally, if not more, exposed. The European Union has practically zero domestic production of separated rare earth oxides or finished magnet materials at scale today. As of the early 2020s, the EU was importing 98% of its rare earth needs from China, according to European Commission data – a near-total reliance. This one-sided dependence leaves Europe’s defence industry and green-tech sector extremely vulnerable. European companies, from missile manufacturers to wind turbine producers, face potential supply shocks if Beijing decides to tighten the tap. A recent analysis highlighted that many EU defence firms simply assume critical materials will be available on the global market and have minimal stockpiles. Should China cut Europe off in a future crisis, production lines for precision munitions, sensors, aircraft and vehicles could grind to a halt within months or even weeks. NATO’s Secretary General has underscored that the Alliance’s technological edge depends on secure access to such materials. In a worst-case scenario, an adversary’s control of rare earth supplies could erode NATO’s military readiness without firing a shot.

The Need for a NATO and European Solution

It is increasingly clear that the West cannot afford to treat rare earths as just another commodity – they are a strategic asset, and their supply chain is a strategic vulnerability. The United States has started to respond with urgency, and Europe is now waking up to the same reality. But a purely American solution is not enough; a broader NATO-wide and European approach is needed to build resilience against supply shocks. This means action on several fronts:

- Diversifying Sources: NATO countries are seeking alternative suppliers of rare earth raw materials outside China. Allies like Australia and Canada, which have significant rare earth deposits, are ramping up production with Western investment. In Africa, too, new mines, often with Western or Japanese backing, are under development. However, while mining can be done elsewhere, the critical bottleneck remains processing. Without access to processing plants, raw concentrates from places like Australia often ended up going to China in the past. Therefore, diversifying sources must go hand-in-hand with building processing capacity in allied countries.

- Onshoring Processing and Manufacturing: Both the EU and U.S. are investing in domestic rare earth separation facilities and magnet factories to break China’s stranglehold on the value-added stages. For instance, the U.S. government in 2025 became the largest shareholder in America’s only operating rare earth mine, as part of a strategy to develop domestic refining and magnet production. Similarly, the EU’s new Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) sets ambitious goals that by 2030, at least 40% of Europe’s demand for strategic raw materials should be refined within Europe, with 10% mined in Europe and 15–25% coming from recycling. Dozens of projects are now underway: from France’s expansion of its La Rochelle rare earth separation plant, to Estonia’s new magnet factory, to planned refineries in Norway and Germany. Still, achieving these goals will be an uphill battle – a recent Reuters analysis concluded the EU will struggle to meet most of its targets by 2030, given the slow lead times and technical hurdles.

- Building Europe’s Rare Earth Capacity: A rare earth processing facility under construction in Narva, Estonia, by Neo Performance Materials. European industry is investing in domestic processing plants like this to reduce reliance on Chinese refineries. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act aims for Europe to process 40% of its own critical minerals by 2030. Companies such as Solvay in France plan to produce neodymium-praseodymium oxides for magnets by mid-decade, targeting to meet 20–30% of European rare earth magnet demand after 2030. Such efforts, alongside new magnet factories in Estonia and recycling initiatives, underscore a drive toward self-sufficiency. However, until these projects reach industrial scale, Europe remains far from self-reliant in rare earths.

- Stockpiling and Contingency Planning: In the immediate term, NATO countries are looking at strategic stockpiles to buffer against a potential cut-off. The idea of a NATO strategic reserve for critical minerals has been floated, and the EU this year released a new stockpiling strategy that, while not defence-specific, includes raw materials relevant to security. Major defence contractors have also started quietly increasing their inventories of rare metals – for example, Europe’s missile maker MBDA said it is boosting reserves of key alloys to mitigate supply disruptions. Stockpiles are a costly insurance policy, but in a crisis, they could buy time for industry to scale up alternative supplies.

- Allied Coordination: NATO as a bloc is beginning to coordinate on this issue. In June 2025, twelve NATO allies launched a new High Visibility Project focused on joint acquisition and management of defence-critical raw materials. This initiative will pool efforts on sourcing, recycling and storing key minerals like lithium, titanium and rare earths, recognising that no single country can tackle this alone. It also underscores the need for NATO-EU cooperation: while NATO brings a security focus, the European Union brings industrial and regulatory tools. The two organisations are increasingly aligned on identifying critical materials and funding projects to secure them. As one report noted, ensuring supply chain security will require “sustained coordination between governments, industry, and international partners”.

- Learning from the U.S. Response: Washington’s aggressive measures – from export controls on semiconductors to subsidies for domestic mines – have in many ways spurred Europe to act. China’s latest countermove should serve as a further wake-up call for European leaders. The American approach has been to treat critical minerals as a strategic domain, with legislation to fund mines (e.g. through the Defense Production Act) and alliances like the Minerals Security Partnership. Europe is now moving in this direction with its own raw materials act and investment in mines from Sweden to Spain. The clear message is that NATO allies must build a parallel supply chain wholly or largely outside of Chinese control. This will not happen overnight and will require difficult choices – including possibly accepting higher costs or environmental trade-offs to develop mines and refineries at home. But the cost of inaction could be far greater if Europe’s defence sector finds itself at China’s mercy for essential inputs.

The Nordic Advantage: Finland and Sweden’s Key Role

In the quest for a more secure rare earth supply, Europe’s Nordic countries – particularly Sweden and Finland – are emerging as linchpins. Both nations, now members of NATO, are endowed with significant rare mineral resources in their northern regions. Unlocking those resources and processing them in Europe, rather than shipping raw ores to China, could substantially bolster NATO’s supply chain resilience.

Sweden made headlines in January 2023 with the discovery of Europe’s largest known rare earth deposit at Kiruna in the Arctic north. State-owned miner LKAB announced over one million tonnes of rare earth oxides in the Per Geijer ore body – a deposit that could eventually supply up to 18% of Europe’s annual rare earth demand. This is a potential game-changer for Europe’s self-sufficiency. LKAB is already piloting extraction of rare earths from existing mine waste, aiming to produce about 2,000 tonnes of RE oxides per year by 2028–2030. The larger Per Geijer deposit will take longer – a decade or more – to develop, but plans are underway. What’s crucial is that Sweden intends not just to mine these materials, but to process them domestically or within Europe, keeping the value chain – and strategic control – at home. As the CEO of LKAB put it, “we must ensure these resources are produced here in Europe, and not simply exported as raw material” – a clear reference to past practices where Europe dug minerals out of the ground only to send them to China for refining.

Finland likewise holds promising reserves. A notable project is the Sokli deposit in Finnish Lapland, rich in light rare earth elements. Now overseen by the state-owned Finnish Minerals Group, Sokli could supply an estimated 10% of the EU’s rare earth needs once it comes online. The Finnish plan is to have it operational by around 2035, pending environmental permits. Additionally, Finland is a significant producer of other critical minerals (like cobalt, nickel and lithium) and has built up processing expertise in those – a strength that can be extended to rare earth refining. Both Finland and Sweden benefit from stable governance and high environmental standards, meaning any mining will be done responsibly by global standards – but it also means projects take time to approve. Even so, these countries are positioning to become the EU’s “internal allies” in securing critical raw materials. Their entrance into NATO further solidifies the notion that the Alliance’s resource security can be enhanced from within its own ranks.

Sotkamo’s Terrafame mine in Finland is one of Europe’s most strategic sources of critical minerals. The operation sits on Europe’s largest nickel ore reserve, with measured, indicated and inferred resources of around 1.5 billion tonnes, containing 3.9 million tonnes of nickel and 0.3 million tonnes of cobalt; it also produces zinc, copper and uranium, all extracted through a low‑carbon bio‑heap leaching process. Terrafame’s integrated industrial site converts this ore into battery‑grade nickel and cobalt sulphates, supplying chemicals for about one million electric vehicles a year and accounting for roughly 70 % of all nickel mined in Europe; by 2030, the company expects to meet more than 10 % of EU demand for battery‑grade nickel and over 1 % for cobalt. Its new Kolmisoppi project, granted strategic status under the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, will extend mine life into the 2050s and strengthen European supply chains, while a recently opened uranium recovery plant, planned capacity 200 t per year, and partnerships on battery‑materials recycling underline its potential to deliver a wider suite of critical materials.

Norway, while not an EU member, is another Nordic NATO ally contributing to the effort. A Norwegian firm, REEtec, is constructing a rare earth separation plant with substantial capacity. Norway also recently announced its largest rare earth deposit (the Fen complex), with plans for production by 2030. Together, the Nordic trio’s initiatives could, in time, provide a significant non-Chinese source of both raw minerals and processed rare earth oxides for the alliance. The Nordic advantage lies not only in resources but also in a shared strategic perspective. Sweden and Finland have witnessed how over-reliance on a single supplier – whether Russian pipeline gas or Chinese minerals – can become a critical vulnerability in times of tension. There is political will in these countries to invest in autonomy. Furthermore, the Nordic countries have strong tech industries, from Finnish electronics and rapidly growing defence sector to Swedish automotive and much bigger defence firms, that stand to benefit from a local supply of rare earths. By processing more of their own raw materials, they also keep the economic value and jobs in-region, rather than exporting raw ores cheaply and buying back expensive finished products. It is a win-win for economic security and national security.

Towards Allied Self-Reliance

China’s recent rare earth export curbs have thrown into sharp relief a strategic weakness for NATO: the alliance’s cutting-edge weapons and technologies depend on materials largely controlled by a strategic competitor. This is a vulnerability that can no longer be ignored. The response must be a united, transatlantic effort to rebuild secure supply chains for rare earths and other critical minerals – an effort that spans from Washington and Brussels to Stockholm and Helsinki.

This means investing in mines, refineries, and factories on allied soil, forging partnerships among NATO members to share resources and expertise, and establishing contingency stockpiles for rainy days. NATO’s deterrence in the 21st century is not just about tanks and missiles, but also about the raw materials that make those systems possible. As China itself has now demonstrated, control of supply chains can be as potent a tool of statecraft as any warship or battalion.

Momentum is building: the United States has treated the rare earth shortage as an emergency, which serves as a wake-up call for Europe to accelerate its own initiatives. NATO’s inclusion of supply chain security in its agenda, and the EU’s new policies, are steps in the right direction. Finland and Sweden, bringing a Nordic backbone of raw materials into NATO, will be central players in this long game. They exemplify how allied nations can contribute not just military forces to the alliance, but also critical resources and industrial capacity.

In the coming years, success will be measured by whether NATO countries can reduce the percentage of rare earths and other critical inputs they source from China. The goal is not total decoupling in one swoop – which is unrealistic in the short term – but to substantially cut dependency so that Beijing’s ability to blackmail or cripple allied industries is minimised. Achieving even a self-supply of 30–40% of key rare earth products by 2030 would greatly enhance security. It would mean that if exports from China stopped, Western defence production could continue, albeit at lower capacity, rather than collapsing outright. Ensuring reliable access to rare earths is about future-proofing NATO’s defence posture. As one European official quipped, “we don’t want to jump from the frying pan of Russian gas into the fire of Chinese rare earths.” The lesson of recent years is that supply dependence on an authoritarian rival is a strategic liability. NATO’s technological supremacy has long been a pillar of its strength; maintaining that edge will require something quite prosaic but utterly vital – secure supply lines for the rare elements that power modern civilisation. By acting now, collectively and decisively, the United States, Europe, and the Nordic partners can turn a critical weakness into a source of strength, ensuring that the alliance’s high-tech armoury is never again at the mercy of a foreign power’s mining and refining apparatus.

Read More:

- CSIS: China’s New Rare Earth and Magnet Restrictions Threaten U.S. Defense Supply Chains

- Reuters: China expands rare earths restrictions, targets defense and chips users

- NDR: The New Arms Race Is Underground: Responding to China’s Resource Blackmail

- IISS: Critical Raw Materials and European Defence

- Al Jazeera: China tightens export controls on rare-earth metals: Why this matters

- Defence Blog: NATO focuses on rare earths for defense

- Reuters: Companies forging a rare earths industry in the EU

- NY Times: In Retaliatory Move, Trump Threatens 100% Tariffs on Chinese Goods

- Terrafame: Sustainability Report 2024

- Terrafame: Terrafame Q1/2025: EBITDA decreased due to lower market prices, battery chemicals production continued to grow

- Invest In Kainuu: Kainuu – Battery production and raw materials – all in one place

- ICMM: Role of Mining in National Economies: Mining Contribution Index (7th Edition, 2025)

- European Commission: European Critical Raw Materials Act

- Chatham House: China’s rare earth export restrictions threaten Washington’s military primacy

- Institute For Energy Research: China Imposes Export Controls on Rare Earth Minerals

- Market Mocha: China’s rare earth restrictions threaten US defence

- Radio Free Europe: Why China Is Flexing Its Dominance Of Rare Earth Minerals In US Trade War

- Wired: Bad News for China: Rare Earth Elements Aren’t That Rare