Elem Klimov’s Come and See (Idi i Smotri) stands as one of the most harrowing depictions of war ever committed to film. Set during the Nazi occupation of Belarus during World War II, the movie blends historical accuracy with a surreal and nightmarish aesthetic, making it a profound anti-war statement. Come and See offers insights into the brutal realities of war, especially the savagery of partisan warfare and the moral degradation of both soldiers and civilians. It is a masterpiece of visual storytelling and psychological depth.

From the outset, Come and See demonstrates a keen understanding of the guerrilla warfare that characterized much of the Eastern Front during World War II, particularly in regions like Belarus, which became hotbeds of resistance against the Nazi occupiers. The film follows the journey of a young boy, Florya, who joins a group of partisans. This depiction of resistance warfare is remarkably accurate in its chaos and brutality. There’s no romanticism here—Florya’s initial excitement is quickly shattered by the devastating consequences of his decision.

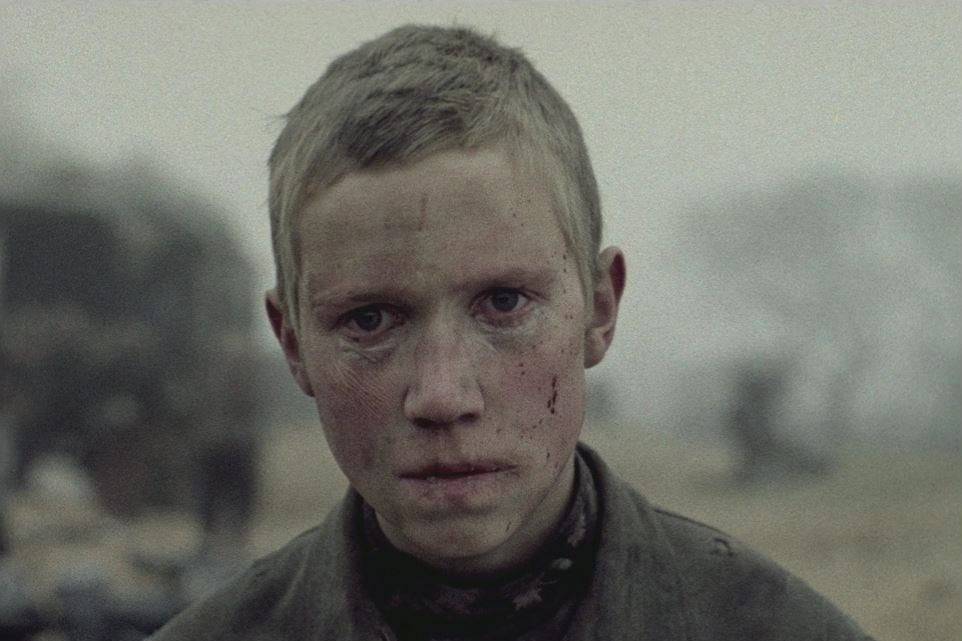

The film vividly portrays the psychological impact of war on soldiers, especially inexperienced ones like Florya. His rapid descent into trauma is one of the most striking aspects of the film from a military psychology viewpoint. Klimov’s decision to have Florya age visibly and dramatically over the course of the film—his youthful face becoming lined and hardened—illustrates the toll that war takes on the human mind. This is a common theme in combat psychology, where prolonged exposure to violence leads to irreversible psychological trauma, a phenomenon observed in many soldiers during intense conflicts.

Zeroing in on the Intimate Atrocities

In terms of tactics and combat, Come and See doesn’t focus heavily on large-scale battles or strategic movements typical of more traditional war films. Instead, it zeroes in on the intimate, ground-level atrocities that civilians and partisans faced, which, while less conventionally “military,” are crucial to understanding the full scope of war. The film’s most devastating sequence, the massacre of an entire village by Nazi forces, is a chillingly accurate portrayal of the real-life war crimes committed during Operation Barbarossa and the Nazi anti-partisan campaigns. This scene reflects the tactics of scorched-earth warfare, where Nazi forces would annihilate villages to intimidate and suppress resistance.

The Waffen-SS and auxiliary collaborators in the film are depicted with terrifying realism, reflecting how German forces, especially the SS, conducted reprisals against civilians. The systematic rounding up and burning of civilians inside a barn is a stark reminder of the actual events that occurred in hundreds of villages across Eastern Europe, including the infamous Khatyn massacre in Belarus – not to mix Poland’s Katyn massacre by the Soviets.

Psychological Warfare and Trauma

The film’s most important contribution is its depiction of psychological warfare, not only between opposing forces but within the mind of the protagonist. Florya’s journey is not a tale of military tactics but a deep exploration of war’s dehumanizing effects. His exposure to the horrors of civilian massacres and the collapse of moral structures reflects the real trauma that many child soldiers and young combatants have experienced in conflicts throughout history.

The film also touches on the concept of survival guilt and the mental fragmentation that soldiers experience when confronted with war crimes. Florya’s interactions with the partisans, his witnessing of atrocities, and his eventual near-catatonic state at the end of the film all illustrate the collapse of an individual’s ability to cope with the enormity of the violence around them. The impact of such psychological strain is well-documented among war veterans and is central to understanding the human experience of warfare.

Visual Tour de Force

Come and See is a visual and auditory tour de force, delivering a visceral experience unlike any other war film. Klimov’s use of long takes, often placing the camera right in the protagonist’s face, allows the audience to experience the war through Florya’s traumatized eyes. This intimate perspective, combined with Aleksei Rodionov’s cinematography, immerses viewers in the horrors of war without the distance that traditional war films provide. The film is filled with stunning imagery: the sudden appearance of bombers over the horizon, the eerie quiet of the forest, and the grotesque scenes of destruction in the aftermath of battle.

The sound design in Come and See is equally powerful. Instead of relying heavily on musical scores, Klimov often uses diegetic sounds—bombs, gunfire, and the terrifying hum of planes overhead—to create tension. At times, the soundscape is distorted, mimicking Florya’s mental deterioration. The scene where he temporarily goes deaf after an explosion is an example of how the film blends technical brilliance with psychological depth, immersing the audience in his disorientation.

Come and See is not just a war movie; it is an anti-war movie in the purest sense. It avoids glorifying battle and instead focuses on the senselessness of violence and the destruction of innocence. By choosing a child as the protagonist, Klimov strips away any potential for heroism, focusing instead on the pure horror of survival in a warzone.

Balancing Realism with Surrealism

One of the most remarkable aspects of Come and See is how it balances realism with a dreamlike, surreal quality. Klimov distorts time and space, making the events feel both immediate and otherworldly. This surrealism serves to heighten the sense of unreality that often accompanies extreme trauma, a phenomenon documented in combat veterans who describe their experiences as if they were watching someone else live them.

One of the most powerful scenes comes at the end, when Florya shoots at a portrait of Adolf Hitler, and the film flashes backward through the war, as if attempting to undo the destruction. It’s a deeply symbolic moment, conveying the futility of trying to change the past or escape the horrors of war. The sequence encapsulates the film’s central thesis: war is a madness that consumes all in its path, leaving only destruction and trauma in its wake.

Come and See is a film that transcends the traditional war genre, offering an unforgettable exploration of the horrors of conflict and the human capacity for both cruelty and resilience. While it is not an easy film to watch, it remains one of the most important war films ever made, and an essential viewing for anyone interested in the true cost of war.