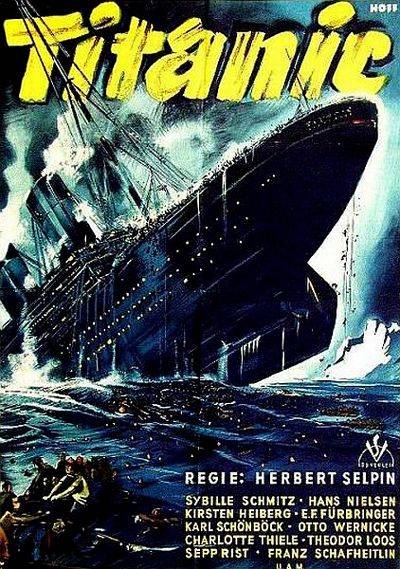

When we think of films about the Titanic, James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster or the British classic A Night to Remember (1958) usually come to mind. Yet in 1943, deep in the Second World War, Nazi Germany produced its own epic retelling of the Titanic disaster. The result is one of the most peculiar and revealing propaganda artefacts of the Third Reich.

Directed first by Herbert Selpin and then, after Selpin’s mysterious death in Gestapo custody, by Werner Klingler, Titanic was funded by Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda ministry and shot with considerable resources. Exterior scenes were filmed on real ships in Gdynia, occupied Poland, notably the SS Cap Arcona, and the film carried production values rare in wartime cinema. It was also hugely expensive at a time when Germany’s economy was under siege.

British Greed Meets German Heroism

The film reframes the well-known maritime disaster as a morality tale of British decadence and German virtue. British shipping magnate J. Bruce Ismay is portrayed as an unscrupulous profiteer, obsessed with stock prices and prestige. Passengers and investors alike are shown scheming over shares, treating the maiden voyage to inflate values on the London market.

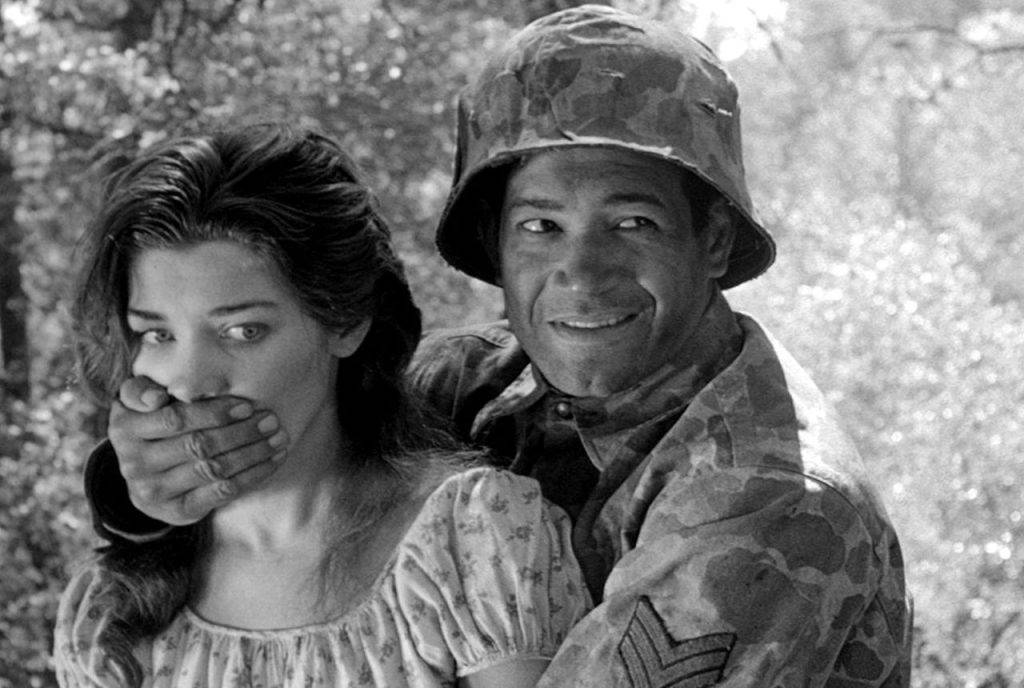

Against this stands the fictional German officer Petersen, the lone voice of reason who repeatedly warns about the dangers of speed and the threat of icebergs. His pleas are dismissed by arrogant superiors. When the inevitable collision occurs, Petersen emerges as the true hero, acting selflessly to save lives while British officers bluster, panic, and shirk responsibility. The contrast is unsubtle: German moral clarity versus British capitalist greed and incompetence.

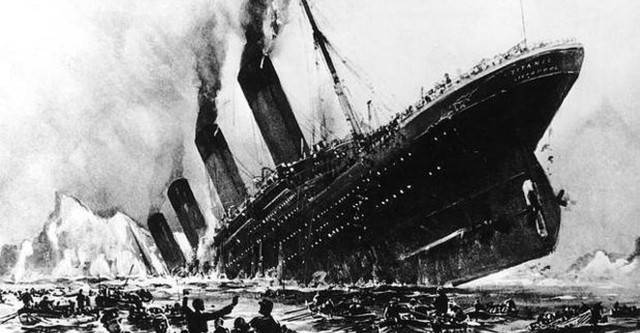

The climactic sinking scenes are impressive for their time. Crowds in chaos, lifeboats lowered too late, and women and children scrambling for safety are all staged with considerable cinematic ambition. The disaster is capped with a moralising epilogue blaming the catastrophe on “the endless quest for profit.” For the viewer, the message is: Britain’s ruling class is corrupt, selfish, and unfit to lead; Germans, even as passengers on a British liner, embody discipline and humanity.

Propaganda That Backfired

The 1943 Titanic is less a film about naval disaster than a study in propaganda under wartime conditions. Its aim was to delegitimise Britain by portraying its society and economy as rotten to the core.

The propaganda logic was simple: if Britain could let 1,500 souls drown for profit, what else might it be guilty of? The parallels with wartime Anglo-German conflict were intended to be obvious.

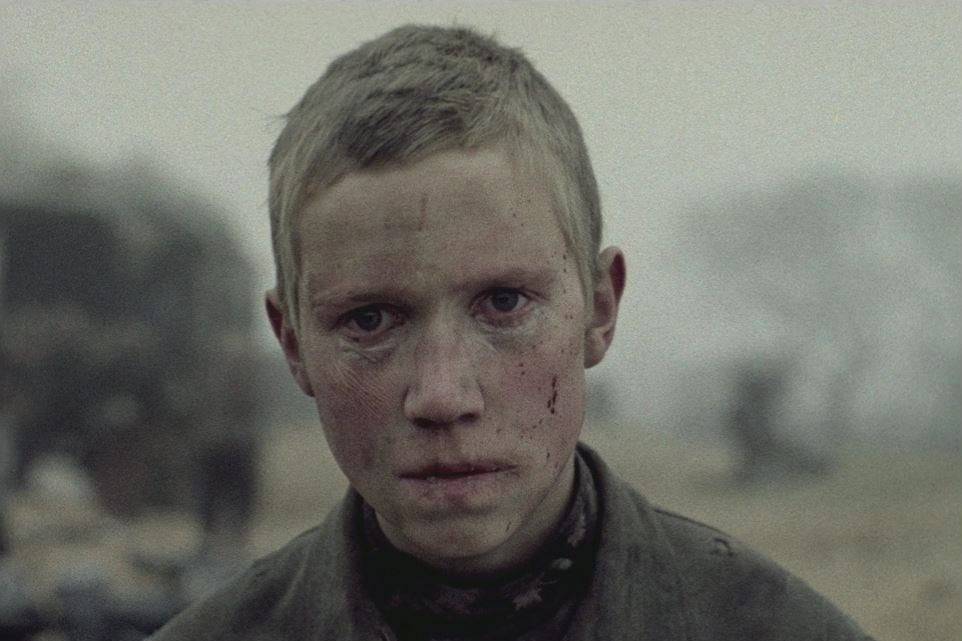

Yet the project backfired. Goebbels soon realised that showing ordinary people panicking and drowning en masse was dangerous at home. German civilians, living through Allied bombing raids, could too easily see themselves in the terrified crowds on screen. The very images meant to vilify Britain risked depressing German morale. As a result, the film was banned from wide release in Germany, screened only briefly in occupied Europe, and largely buried. It was propaganda too dark even for the Nazis.

This also reveals a deeper contradiction. The hero Petersen challenges incompetent superiors, defies orders, and stands for moral responsibility over hierarchy. Within the Nazi regime, where obedience to authority was paramount, such a portrayal was double-edged. Even when wrapped in anti-British messaging, the implicit criticism of leadership did not sit comfortably.

Corruption, Inefficiency, and Misconduct

The making of Titanic was as troubled as its subject. Director Herbert Selpin complained openly about corruption, inefficiency, and misconduct among military officers attached to the production. He was arrested by the Gestapo and died in custody, officially a suicide but widely suspected to have been murdered. Werner Klingler finished the film. That grim backstory reinforces the impression that this was a cursed production.

On screen, however, the film spares no expense. Sets are detailed, the sinking sequences well staged, and for wartime Germany the spectacle is extraordinary. Yet the pacing drags during scenes of shareholder scheming, and characterisation is bluntly propagandistic. Subtlety was never the point.

Because it was pulled from German cinemas, Titanic never achieved the propaganda impact its makers intended. After the war, Allied authorities and later German distributors hesitated to show it, though cut versions surfaced. Today, it survives mainly as a curiosity for historians and cinephiles: a reminder of how even the Titanic tragedy could be pressed into service for ideology.

Compared with later films on the subject, it is strikingly crude in its politics. A Night to Remember (1958) emphasised professionalism and tragedy, Cameron’s Titanic (1997) romantic melodrama and spectacle. The Nazi version is less about the sinking and more about blaming Britain, its characters reduced to symbols in a morality play.

Titanic (1943) is uneven but historically fascinating. Its disaster sequences stand out, but heavy-handed propaganda undermines narrative flow. It is a propaganda film masquerading as a disaster drama, and yet its very flaws make it compelling for those interested in how regimes use cinema.