What really drove the Kremlin during the Cold War—wild-eyed dreams of global communism, or cold-blooded fear for its own survival? The answer matters because the same instincts may still shape Moscow’s next moves. According to Melvyn P. Leffler, the binary view of ideology versus security is overly simplistic. Understanding the Kremlin’s motivations is crucial to countering and deterring Russia’s contemporary expansionist ambitions.

The Soviet Union’s foreign policy during the Cold War was deeply influenced by a pervasive sense of insecurity and fear of encirclement. This apprehension led to defensive expansionism, where the USSR sought to establish buffer zones by exerting control over neighboring countries. Notable examples include the invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, aimed at suppressing movements perceived as threats to Soviet hegemony.

This strategy was encapsulated in the Brezhnev Doctrine, which asserted the USSR’s right to intervene in any socialist country deemed to be veering away from the principles of socialism. The doctrine underscored the Soviet leadership’s commitment to maintaining a sphere of influence as a security measure against potential Western aggression.

For decades, Western policymakers viewed the Soviet Union as an ideologically fanatical power, bent on spreading communism by any means necessary. But as Melvyn P. Leffler shows in his Foreign Affairs essay Inside Enemy Archives, published in 1996, the truth is far more nuanced — and far more uncomfortable. The Kremlin, documents opened in the 1990s suggest, was guided less by utopian dreams of Marxist revolution and more by classic statecraft: fear, insecurity, and the need to survive in a hostile world. This wasn’t the Soviet colossus of Reaganite rhetoric. It was a wounded giant, still reeling from two world wars, terrified of a resurgent Germany, spooked by an atomic-armed America, and struggling to maintain control over its own backyard. The Cold War, it turns out, wasn’t just about ideology — it was about insecurity, improvisation, and sometimes outright panic.

Soviet Support for Liberation Movements

The Soviet Union’s foreign policy was deeply rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, which envisioned a global proletarian revolution leading to a classless, communist society. This ideological commitment was not merely rhetorical; it influenced the USSR’s interactions on the international stage. Proletarian internationalism, a core of Soviet ideology, emphasized solidarity among working-class movements worldwide and supported anti-imperialist struggles. This principle justified Soviet support for communist parties and liberation movements across the globe, from Asia to Latin America. However, the application of proletarian internationalism evolved. In the immediate post-World War II period, the USSR established “people’s democracies” in Eastern Europe, aligning these nations with Soviet interests. By the 1960s, the concept of socialist internationalism emerged, focusing on diplomatic and political solidarity among existing socialist states rather than actively promoting revolution. This shift indicated a more pragmatic approach, balancing ideological commitments with geopolitical realities.

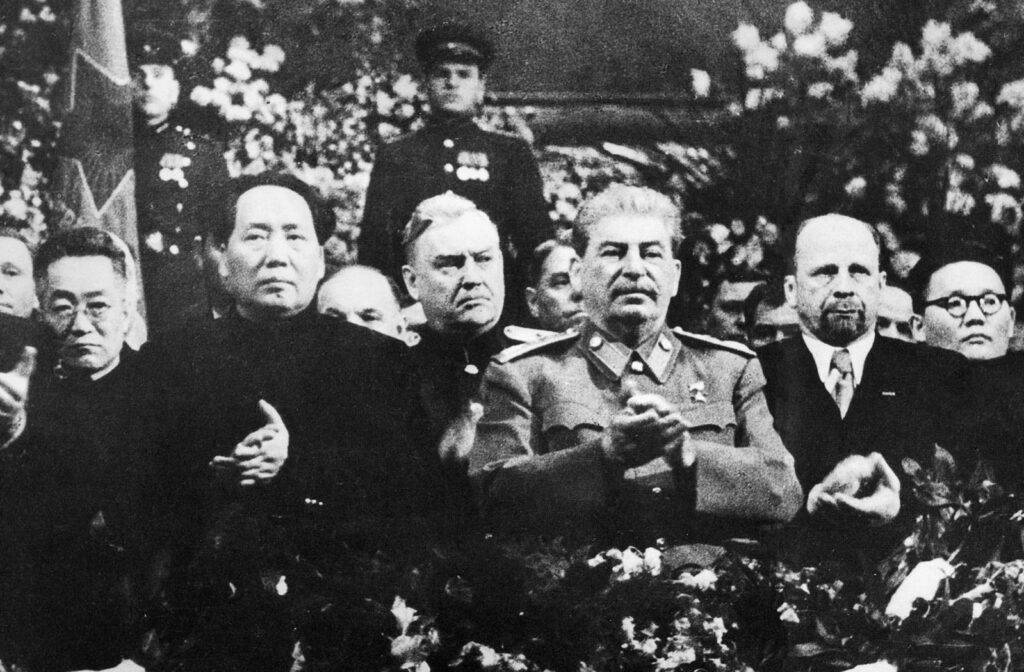

Mao Zedong, Nikolai Bulganin, Walter Ulbricht, and Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal at Stalin’s 70th birthday celebration in 1949. (Image: Wikipedia)

While ideology played a significant role, security concerns were paramount in Soviet foreign policy decisions. The devastation experienced by the USSR during World War II fostered a deep-seated desire to prevent future invasions, leading to the establishment of a buffer zone of friendly governments in Eastern Europe. These satellite states served as a protective barrier against potential Western aggression.

No Master Plan for Germany

Take Germany. The Cold War’s symbolic and literal fault line. Western observers long claimed that Stalin sought to sovietise Germany from the outset. However, as historians Norman Naimark and Leffler show, Soviet actions in East Germany were inconsistent and reactive. There was no blueprint like the Americans’ JCS 1067. Moscow vacillated—at times pushing for a unified Germany, at others looting the eastern zone for reparations. In the end, East Germany became communist not through some Soviet grand design, but because chaos reigned, and communists were the only ones with Red Army backing and organizational muscle.

Poland, Hungary, and the Balkans: Improvised Control

The same pattern repeated across Eastern Europe. Stalin famously told the Polish Peasant Party leader Stanislaw Mikolajczyk that communism fit Poland “like a saddle on a cow.” He wasn’t lying. The Kremlin never had a clear vision for turning Poland, Hungary, or Romania into Marxist utopias. In Poland, internal chaos, Nazi devastation, and local communist aggression forced Moscow’s hand. Soviet-installed regimes acted brutally, but they often improvised their way into power rather than follow central directives.

China: Stalin’s Reluctant Revolution

Even in China, Soviet ideology took a backseat to geopolitical caution. Stalin initially preferred a deal with the Nationalists and only gradually supported Mao’s rise. According to Norwegian historian Odd Arne Westad, the Kremlin saw Northeast Asia as a fragile zone where American military presence needed to be checked, not a theatre for exporting revolution.

Security, Not Ideology

Again and again, documents reveal that what looked like revolutionary aggression was often reactive paranoia. After suffering 27 million deaths in WWII, the Soviet leadership was traumatized. Stalin feared a remilitarized Germany, a resurgent Japan, and an unpredictable United States armed with nuclear weapons. Far from plotting global conquest, the USSR built defensive buffers—militarily, economically, and politically. Leffler and David Holloway point to Soviet war plans in 1946–47 that were defensive by nature. There was no plan to invade Western Europe—only to retreat and counterattack if the West struck first.

Clients in the Driver’s Seat

Even some of the USSR’s most infamous Cold War moves—such as the Korean War and the Berlin Wall—were pushed forward by overzealous clients. North Korea’s Kim Il Sung pestered Stalin into greenlighting the invasion of the South. East Germany’s Walter Ulbricht browbeat Khrushchev into backing the Berlin Wall to halt a brain drain. The Kremlin wasn’t pulling all the strings; it was often being yanked by them.

Angola and Afghanistan: Ideology Used, Not Obeyed

In Angola, it was Fidel Castro—not the Soviets—who took the initiative to back the MPLA. Moscow only stepped in after South Africa’s intervention forced their hand. In Afghanistan, the Kremlin had little interest in intervention until the ruling Khalq faction’s reckless policies, internal chaos, and rising Islamic fundamentalism made the situation impossible to ignore. The 1979 invasion was about stability on the USSR’s Muslim frontier, not Cold War domination.

Ideology as Window Dressing

Yes, the Soviet elite believed in Marxist theory. But they used it more as PR than as an operational doctrine. It helped justify what they were doing anyway—establishing control, countering threats, and staying in power. Stalin backed coalition governments in Western Europe when communists could win freely, discouraged Mao’s aggression, and refused to aid the Greek left in its civil war. These were hardly moves of a leader bent on global revolution.

The American Role: Feeding the Fear

But the USSR didn’t operate in a vacuum. U.S. actions often deepened Soviet paranoia. The Marshall Plan, though a brilliant reconstruction effort, was seen in Moscow as a Trojan horse designed to lure Eastern Europe out of its orbit. The atomic bomb, unveiled without warning at Potsdam, confirmed Soviet fears of U.S. strategic dominance. In response, Stalin cracked down across Eastern Europe and accelerated Soviet bomb development. Historian David Holloway argues convincingly that the bomb didn’t cause Soviet belligerence—but it locked the Soviets into a realist mindset. Power had to be balanced. Weakness would invite attack.

No Moral Clarity, Just Brutal Calculations

The new documents also strip away illusions of moral clarity. Both sides saw themselves as reacting to the other’s aggression. Each mistook defensive moves for offensive ones. U.S. policymakers viewed Soviet moves through the lens of totalitarian ambition; Soviet leaders saw American aid and alliances as capitalist encirclement.

This misunderstanding meant lost opportunities. Leaders like Beria—yes, Beria—briefly floated détente ideas after Stalin’s death, even suggesting German reunification. But infighting and fear of appearing weak killed the initiative. The Cold War intensified, and a global arms race took off.

Not a Red Menace, but a Fortress State

Leffler’s deep dive into Soviet archives in the 1990s, supported by scholars like Westad, Holloway, and Zubok, reshapes our understanding of the Cold War. The USSR was not a juggernaut of Marxist ambition. It was a wounded giant, fearful of encirclement, obsessed with security, and guided by brutal pragmatism.

Western containment may have been necessary, but it wasn’t flawless. It often made things worse. By misunderstanding the Kremlin’s fears, the U.S. helped turn them into reality.

The lesson? Misreading your adversary’s motives is a surefire path to unnecessary escalation. And in today’s world—where Russia once again acts from a place of insecurity—understanding the past is not just academic. It’s vital.

Opposing Russia’s Expansionism

In contemporary times, Russia displays behaviour reminiscent of the Soviet era, though it no longer invokes Marxist-Leninist ideology. The heyday of Stalin and Soviet power, when the USSR was a formidable rival to the United States, is nostalgically cherished by Putin’s regime.

It is driven by a desire to reclaim its perceived sphere of influence and counter NATO’s eastward expansion. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine are manifestations of this expansionist agenda. These actions reflect a continuity in Russian strategic culture, where projecting power is seen as essential to national security.

The international community needs to respond with a posture of strength when opposing Russia’s expansionist moves. A robust and united stance serves multiple purposes:

- Deterrence: Demonstrating military readiness and the willingness to defend allied nations can dissuade Russia from pursuing aggressive actions. For instance, Estonia’s recent fortification of its border with Russia, including the construction of new military bases, exemplifies proactive measures to enhance defense capabilities.

- Preservation of International Order: Allowing unchecked territorial expansion undermines the rules-based international system established post-World War II. Firm opposition to such actions is necessary to uphold international law and norms

- Support for Sovereignty and Democracy: Standing against expansionism is also a stand for the sovereignty of nations and the right of peoples to self-determination, free from external coercion.

Learning from the past, a strategy that combines military preparedness, economic sanctions, and diplomatic efforts is essential to counter and deter Russia’s expansionist ambitions. Such an approach not only protects individual nations but also maintains global stability and the integrity of the international order.

Read More:

- Notre Monde: The Soviet War in Afghanistan | Overview, Causes & Timeline

- The Guardian: Trump’s expansionism threatens the rules-based order in place since the second world war

- Le Monde: Estonia ramps up ‘fortification’ of its border with Russia

- Foreign Affairs: Inside Enemy Archives (published in 1996)