For more than a century, popes have attempted to influence the hard calculus of war: mobilisations, ceasefires, intelligence backchannels, nuclear thresholds and geopolitical realignments. Despite possessing no army, the Holy See has often functioned as a strategic mediator — a unique actor able to interact with military powers during crises when other channels were frozen.

In late 2025, the newly elected Pope Leo XIV made his first overseas trip to Türkiye and Lebanon. His arrival drew ecstatic public receptions. In İstanbul and Ankara, crowds greeted him enthusiastically. Reuters reported that as Leo’s motorcade entered Türkiye’s capital, “hundreds of excited onlookers gathered… amid shouts of ‘Viva il Papa’”, and a traditional dance band welcomed him, beating drums. In Lebanon, scenes of popular fervour were even more striking. Thousands of young people gathered in Beirut before dawn, waving Vatican and Lebanese flags and singing in his honour. During the Dec 1 visit to the Maronite Patriarchate at Bkerké near Beirut, locals held an all-night vigil of prayer and procession before the Pope’s arrival. The National Catholic Register reported that “throngs of people” waited in the square, cheering as Leo XIV descended from his Popemobile.

The crowds braved sun and even rain to greet him. Reuters noted umbrellas shading the faithful at the waterfront Mass where an estimated 150,000 attended. One Lebanese student said volunteers came before dawn to prepare, hoping Leo’s presence would be “a sign of hope coming back to Lebanon”. The atmosphere recalled Lebanon’s history of religious devotion; news reports mentioned drumming bands and festivities. In an open-air meeting that evening, Pope Leo held an all-night youth vigil – a torch-lit, candlelit gathering with music and prayers. An official Vatican News schedule emphasised ecumenical prayer, but local Christian youth groups organised the vigil.

In his speeches, Leo XIV balanced warmth and urgency. He explicitly appealed for peace and stability, reflecting regional tensions. In Turkey, he praised Türkiye’s potential as a “bridge” between the West and the Middle East and reaffirmed the Holy See’s support for peace-building. In Lebanon, he publicly urged Lebanese factions to maintain ceasefires and refrain from entering the Gaza conflict. At Beirut’s waterfront Mass, he warned against a “path of mutual hostility and destruction”. He visited the site of the 2020 Beirut port blast, laying a wreath and embracing victims’ relatives. At a psychiatric hospital run by nuns, he prayed with survivors and promised to “raise his voice for justice” for the victims. Throughout, his message combined moral authority and diplomatic tact: he spoke in terms of human suffering and Christian responsibility, yet never explicitly criticised any government by name. Instead, he framed peace as both an urgent human need and a Catholic mission, calling on “all nations” to respect sovereignty and end hostilities. In private meetings, too, Leo XIV engaged leaders of all faiths and states. The trip concluded with renewed Vatican appeals for ceasefires and negotiations – a pattern familiar from past papal diplomacy.

Benedict XV and World War I: “Futility of War”

The Vatican’s modern diplomatic engagement began with Pope Benedict XV (1914–1922). Within weeks of WWI’s outbreak, Benedict issued the 1914 encyclical Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, famously decrying the “suicide of civilised Europe” and calling soldiers to lay down arms on Christmas Eve so “guns may fall silent”. This papal plea, however, went unheeded by the governments, though small, unsanctioned truces did occur on Christmas 1914. Benedict intensified his efforts in 1917 by issuing a “peace note”. This diplomatic proposal set out seven points: an immediate ceasefire, freedom of the seas, reduction of armaments, mediation by neutral powers, the restoration of invaded territories, and postwar arbitration for grievances. He wrote to each belligerent head of state, urging them to adopt his plan. Although the Allies dismissed it as a return to the status quo ante, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson later incorporated several of Benedict’s ideas into his famous Fourteen Points. Yet Benedict was excluded from Versailles and had no voice in the war’s settlement.

Though rejected, the Vatican forced major powers to publicly articulate their war aims, revealing internal fractures, especially in Austria-Hungary, where peace factions gained momentum.

- Peace initiatives: Benedict’s 1917 Pax note called for ceasefires and international arbitration.

- Condemnation of chemical weapons: Influenced post-war discussions on arms regulation, later reflected in interwar treaties.

- Humanitarian aid: Beyond proposals, his Church organised relief, like ambulances, hospitals, and negotiations for POW swaps.

- Limits: Critics note Benedict’s inability to sway major powers. Historian John Wilsey argues the Peace Note “arrived too late” and was politically sidelined. Nonetheless, Benedict’s advocacy did set a precedent for Vatican soft power: he appealed to conscience and Christian ethics, rather than sanction or force. He was widely dubbed a “Pope of Peace” for his stance.

After the Armistice, Benedict continued urging reconciliation. In his 1919 encyclical Pacem, Dei Munus Pulcherrimum, he warned that Versailles’ punitive terms risked future conflict. Benedict offered ecclesiastical mediation to heal “hatred and bitterness”, foreshadowing later calls for a new order. Although the League of Nations, to which the Holy See was then observer, did not involve the Vatican directly in politics, Benedict’s postwar messages exemplified the Vatican’s self-conceived mission as moral conscience – an early form of soft-power diplomacy.

Pius XII and World War II: Intelligence and Intervention

Pope Pius XII (1939–1958) presided during WWII. The Vatican maintained official neutrality, but its vast diplomatic network became an intelligence source. In 2000, a Guardian investigation reported that the Vatican received “excellent intelligence” throughout Europe about the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, from Catholic bishops and diplomats in both Axis and occupied countries. German historians later confirmed Pius XII was aware of death camps and mass murders by 1942. Yet he largely remained publicly silent on the specifics. In late 1942, he issued Summarium Pontificum, a carefully worded statement about “hundreds of thousands” being killed, stopping short of naming Hitler or Nazis. Pius warned in general terms against genocide and quietly aided some refugees. For example, in 1944, the Vatican intervened with Hungarian regent Horthy to delay the deportations of Jews. But his refusal to explicitly condemn Hitler’s regime has been widely debated as a moral failure, even as Catholic diplomats helped hide fugitives.

- Just war and nuclear age: Pius XII was profoundly concerned with modern warfare. In 1946, he called nuclear weapons the “most terrible weapon the human mind has ever conceived”. His speeches at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1941–45 warned that atomic energy must be “used for peaceful purposes” only, or “catastrophic” consequences would follow. He declared that nuclear bombs would violate the just-war principle of proportionate force. Nonetheless, he affirmed that nations have the right to self-defence if attacked, a stance consistent with Catholic doctrine. Pius’s nuanced position reflected Vatican strategic thinking: abhorring total war and genocide, but upholding the moral legitimacy of resistance once injustice proved unbearable.

- Diplomatic actions: Unlike Benedict XV, Pius was involved in high-level diplomacy during war. The Vatican hosted secret negotiations, e.g. Vatican intermediaries helped negotiate the Armistice of Cassibile between Italy and the Allies in 1943. He also maintained dialogues with heads of state after the war. For instance, Pius expressed hope in 1947 for European reconciliation and warned against “new extremist movements”. Yet some scholars argue that his staunch anti-communism, rooted in Catholic social teaching, limited his ability to push for compromise in the emerging Cold War.

Pius XII leveraged informal influence. He had unique access to information, from clergy and spies, and moral authority, but chose cautious intervention. His consistent emphasis on peace and human dignity laid the groundwork for later papal peace efforts, even as his wartime reticence illustrated Vatican diplomacy’s constraints.

John XXIII and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Pope John XXIII (1958–1963) revived active peace-making. His 1962 encyclical Pacem in Terris called nuclear deterrence a “necessary evil” but insisted that enduring peace “cannot consist in an equal supply of armaments”. John’s most dramatic intervention came during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the world teetered on nuclear war. Addressing Vatican diplomats on 12 October – while the crisis was unfolding – he urged them to heed “the anguished cry” for peace rising “from every part of the world”. He framed this not as political posturing but a moral imperative: “heads of state… must omit no effort to achieve peace”.

Behind the scenes, Pope John offered mediation. According to secondary accounts, U.S. President Kennedy, a Catholic, consulted John by telegram when tensions peaked. John composed a radio message urging all governments “not to remain deaf” to the “cry of humanity” for peace. This appeal – broadcast internationally, even in the Soviet press – reportedly gave Soviet Premier Khrushchev a face-saving exit: withdrawing missiles could be cast as an act of peace rather than defeat. Two days after John’s broadcast plea, Khrushchev indeed announced Soviet withdrawal; the crisis ended without war. Kennedy then quietly agreed to remove American missiles from Turkey. John, seriously ill with cancer, would die months later.

John XXIII’s actions exemplify Vatican soft power: he could not command armies or sanction nations, but his moral voice and network provided critical “cover” for diplomacy. He demonstrated that in nuclear diplomacy, papal influence was purely normative – supplying legitimacy and moral pressure. As he famously said, “negotiating is never a surrender.” His example inspired subsequent popes to frame global conflicts as moral issues requiring dialogue.

John XXIII’s intervention during the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) is one of the clearest examples of papal diplomacy influencing global military decision-making.

- Radio message on 25 October 1962 called for Washington and Moscow to “respect the rights of humanity.”

- Kennedy and Khrushchev both cited the Pope’s intervention as a stabilising influence.

- The Vatican served as a non-aligned moral communicator, reducing miscalculation risk and adding political cover for compromise.

Historians consider this a case where papal diplomacy directly contributed to nuclear de-escalation, arguably the most consequential papal intervention of the century.

Paul VI and the Cold War

Pope Paul VI (1963–1978) inherited John’s mantle of détente. He navigated the Vatican through the tense 1960s and 70s, renewing East–West dialogue and opposing nuclear escalation. Continuing John’s course, Paul called any “peace… based on nuclear deterrence” a “tragic illusion”. At the United Nations in 1965, he appealed for general disarmament and warned against bloc polarisation. Paul VI’s diplomacy helped shift Western strategic thinking toward détente. He encouraged Washington to pursue negotiations rather than military escalation. He promoted early discussions on European arms control, contributing to the intellectual groundwork behind the Helsinki Final Act (1975). His 1965 UN speech advanced the concept of global collective security as an alternative to power politics.

- Ostpolitik: Paul’s hallmark was Vatican Ostpolitik – diplomatic outreach to Communist countries. Recognizing that outright hostility failed, he established formal ties with Eastern Bloc states and negotiated with regimes like Romania’s Ceaușescu and later Poland’s Jaruzelski. He sought to protect Catholic communities behind the Iron Curtain by quietly engaging their governments. This approach represented a “complete departure from Pius XII’s vocal anti-communism”. It helped ease church–state tensions – for example, he secured pilgrimage visas for Polish Catholics. He also preserved a Vatican role in Europe’s strategic balance.

- Peace efforts: Paul VI sent peace letters to Presidents Johnson and Ho Chi Minh in early 1967, urging extension of the Vietnam War’s Tet truce and negotiation. Johnson’s response was courteous but firm, willing to negotiate only if North Vietnam ceased bombing. The Pope’s gesture, however, marked the Holy See as a global advocate for peace, and publicised the moral cost of war, even if it did not end the conflict. During the Cold War, Paul also hosted or convened summit-level diplomacy, such as inviting Congo’s warring leaders for talks, and encouraged peaceful conflict resolution in Africa.

Under Paul VI, the Vatican increasingly positioned itself as a neutral mediator. His foreign policy signalled that the Church no longer identified as a Western power but as a global institution. In the Korean War armistice negotiations and in African decolonisation talks, the Holy See often acted through local episcopal conferences or service organisations. In 1968, Paul VI issued Populorum Progressio, linking social justice to peace, and commended the idea of a united Europe as a path to prevent war. Academics have noted that Paul’s diplomacy was pragmatic: he emphasised values, human rights and religious freedom over ideological bloc loyalties. While limited in power, the Vatican under Paul leveraged its neutrality to host dialogues and quietly encourage reforms, e.g. urging humane treatment of political prisoners in Poland.

John Paul II: Fall of Communism and Latin American Crises

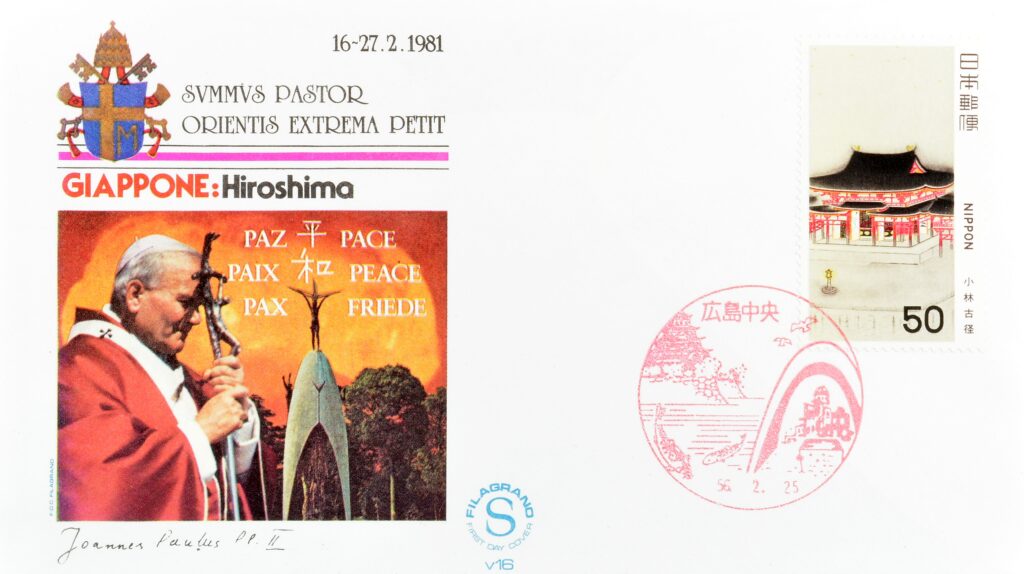

Pope John Paul II (1978–2005) brought his own lived experience of communist oppression to the papacy. As the first Polish pope, he quickly became a moral inspiration in Eastern Europe. During his 1979 visit to Poland, he famously urged Poles to “be not afraid” of tyranny, energising the anti-communist Solidarity movement. His weekly radio messages from Rome kept the idea of human rights alive behind the Iron Curtain. Scholars attribute considerable influence to John Paul’s engagement with Soviet leaders, seeing his pontificate as a major factor in the Cold War’s end. The Vatican’s nonviolent emphasis on human dignity and religious freedom eroded communist legitimacy. Concurrently, John Paul II engaged in global crisis diplomacy. He took initiatives in Latin America, where he was born, and elsewhere. A key example was the Beagle Channel conflict between Chile and Argentina (1978–1984). When war loomed over the disputed southern archipelago, both countries asked the Vatican to mediate. John Paul, together with local bishops, arranged negotiations at the Vatican and in the Italian community of San Egidio. The Holy See’s intervention culminated in the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, which peacefully resolved the territorial dispute. Vatican News later commented that John Paul II played “a crucial role in mediating” this conflict, providing a model of dialogue rooted in “justice, international law, and the exclusion of force”.

- Humanitarian and moral appeals: John Paul frequently called for peace in war zones. He publicly condemned Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait (1990) and urged negotiations, even threatening interdiction on leaders who would block peace. He spoke against ethnic cleansing in the Balkans and sent personal envoys to conflict zones like Bosnia. In 1995, at the height of the Bosnian war, he dispatched Cardinal Casaroli as a special envoy to both sides. Though seldom in headlines, the Pope’s quiet pressure on Catholic leaders in Yugoslavia is credited by some with bolstering the Dayton peace talks.

- Western Hemisphere: After the Chile–Argentina success, John Paul II visited troubled regions to promote reconciliation. In Central America, he negotiated with guerrilla and government leaders during civil wars. He interceded in Nicaragua’s 1985 conflict and helped free hostages in El Salvador. His presence at summits like the UN was leveraged to support peace agreements. In Africa, his involvement in ending Apartheid had a moral effect: he made the struggle against racism a global cause. In all, John Paul II exemplified the Vatican’s strategic use of moral suasion: his status as a saintly figure gave weight to appeals for negotiation.

Nevertheless, the Pope’s direct influence had limits. He could not compel secular leaders to act if they lacked political will. While the Argentine–Chile case showed real diplomatic weight, many of his peace messages were sometimes heeded more by public opinion than by policy-makers. In Cold War Europe, the Vatican lacked formal authority, yet its network of clergy and dissenters made it a node in the chain of events leading to 1989. Overall, his legacy was to maximise symbolic power – using pilgrimages and prayers as tools in international politics.

Benedict XVI: Dialogue and Counter-Radicalisation

Pope Benedict XVI (2005–2013) focused on intellectual engagement and interreligious dialogue in a post-9/11 world. Early in his reign, he reaffirmed the Church’s commitment to peace, and in 2008 addressed diplomats in Türkiye, saying that “dialogue can help end terrorism, war, [and] strife.” He sought common ground with Muslims, encouraging discussions on shared values, though his 2006 Regensburg lecture later caused controversy by criticising theological links between Islam and violence, leading to international protests. Benedict’s approach was to promote understanding of Christianity and Islam as “sisters” sharing a belief in one God. He hosted meetings with Sunni and Shia leaders, such as the historic 2006 trip to Turkey where he met with Muslim scholars, including a landmark address at the Blue Mosque, to foster peaceful coexistence.

On countering radicalisation, Benedict emphasised that extremism has political causes. He argued that eliminating injustice and poverty is vital to prevent violence. In 2005, he set up a Council for Interreligious Dialogue and often preached that true religious teaching precludes terrorism. For instance, after the 2006 Mumbai attack, he declared those attacks “obscene” and demanded that religions not be abused by the “horror of hatred.” While not directly negotiating ceasefires, Benedict’s strategy was to delegitimise extremism and empower moderates. His legacy includes Vatican support for educational initiatives and dialogues intended to undercut ideological extremism – the spiritual front of what academics call “counter-radicalisation.”

However, Benedict’s diplomatic impact was more symbolic than practical. His emphasis on truth and reason was framed by many commentators as “principled but limited.” He did not dispatch mediators in conflicts as frequently as his successor, but he did convene meetings, like joint prayer events with other faiths, and vocally criticised violence. In nuclear diplomacy, he maintained John Paul’s line: reiterating that war “can no longer be considered a legitimate instrument” and advocating global disarmament. Overall, Benedict used the Vatican’s soft influence – theological arguments and cultural persuasion – to promote peace and mutual understanding, though critics argue such methods had a modest geopolitical effect.

Francis: Global Peacemaker in the 21st Century

Pope Francis (2013–2025) continued and expanded the Vatican’s role in mediating contemporary conflicts. His approach was unabashedly global and personal. He repeatedly traveled to conflict zones and met with warring leaders, underlining that “no one should remain deaf to the cry for peace” rising from war-torn peoples.

- Ukraine (2022–2024): Following Russia’s 2022 invasion, Francis had been among the most vocal religious leaders urging an end to hostilities. He hosted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in the Vatican multiple times, most recently in October 2024, and emphasised that “all nations have the right to exist in peace and security”. In his Christmas 2023 “Urbi et Orbi” address, he called for a “ceasefire now” and said Ukraine’s resistance deserved “the honour of arms” but also urged negotiation. In a March 2024 interview, Francis used the metaphor of the “white flag”, arguing that the “strongest” leader is one who has the courage to negotiate peace. He insisted negotiation was not surrender, and volunteered himself as mediator (“I am here”) to help broker talks. Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Parolin reiterated that peace requires talks, not conquest. While no formal Vatican-led peace talks have yet occurred, as both Ukraine and Russia remained firm in their positions, the Holy See’s proposals for exchanges of prisoners and humanitarian gestures have been publicised. Analysts note Francis’s neutrality; he did not take sides but consistently appealed to both governments to engage. As Vatican News reported, parties said they felt the Pope’s presence and prayers influenced them to resume negotiations, the January 2020 “Rome Declaration” ceasefire was credited partly to Francis’s involvement.

- Colombia (2015–2016): On 16 June 2015, Francis offered to mediate Colombia’s peace talks with the FARC guerrillas. Meeting President Juan Manuel Santos at the Vatican, he said he was “willing to assume any role necessary” to help reach a final accord. Santos confirmed the Pope’s offer and placed Vatican diplomats at the negotiators’ disposal. Although peace was ultimately achieved through direct talks in Havana, with Vatican moral support but no military leverage, Francis’s gesture was widely seen as vital encouragement. He also cancelled a planned Colombian visit until peace was in hand. In 2016, the Colombian congress ratified the FARC peace agreement, with many pointing to the Vatican’s influence as a factor in persuading sceptics. Francis later visited Colombia (2017) to pray with victims and reaffirmed reconciliation, showcasing the Catholic Church’s continued role in healing post-conflict divisions.

- South Sudan (2019–2020): Francis worked tirelessly to end the world’s newest civil war. In April 2019, he personally hosted President Salva Kiir and opposition leaders in the Vatican, shepherded by the Sant’Egidio Community. His spiritual retreat for the parties was followed by a “Rome Declaration” on 13 January 2020, which set a new ceasefire and road map for talks. Vatican News reported that both the government and rebels “were humbled and deeply motivated by [Pope Francis’s] relentless ‘spiritual and moral appeal for peace’”. A South Sudanese leader later said, “How can we not bring peace if the Pope pushes us to do so?”. As the Vatican noted, the Pope’s constant dialogue with them and appeals to conscience were decisive. While a final comprehensive peace deal still faces hurdles, Francis’s moral pressure and the Vatican’s convening power helped restart negotiations on the conflict’s root causes.

- Other conflicts: Francis extended the Vatican’s mediating brand to many fronts. He played a behind-the-scenes role in thawing U.S.–Cuba relations, culminating in 2014, praised as unprecedented Vatican diplomacy. In the Middle East, he urged Israeli and Palestinian leaders toward a two-state solution and condemned violence on all sides. In East Africa, he brokered an end to long-standing turmoil between Ethiopia and Eritrea (2018), inviting leaders to the Vatican and calling for regional reconciliation. For the Syrian conflict, Francis advocated humanitarian corridors and hosted refugees, though inter-state mediation was limited by the complexity of that war. In each case, he leveraged the Vatican’s neutrality: officials report that envoys of Francis have quietly met foreign ministers and offered Vatican good offices when requested.

Francis’s impact is mixed. He did not wield coercive power, but his interventions shaped international discourse. By going directly to populations, like praying in a Baghdad church in 2021, he built public pressure for peace. His calls for negotiation, even when controversial, as in urging Ukrainians to negotiate, keep dialogue on the agenda. Where formal peace accords were achieved, the Vatican often served as a moral guarantor. Yet in entrenched conflicts like Ukraine or Gaza, the Pope’s role remained that of proposer rather than broker: he can light the candle, but states must agree to negotiate. Overall, Francis epitomises Vatican soft power: using personal engagement and principled appeals to advance peacemaking.

Leo XIV (2025– ): Re-entering the Middle Eastern Strategic Arena

Leo XIV’s first foreign trip to Turkey and Lebanon emphasised:

- Reducing inter-religious tensions that fuel proxy conflicts.

- Encouraging non-sectarian political reform in Lebanon, a state where armed groups exploit sectarian paralysis.

- Supporting refugees and displaced populations, impacting

- Reinforcing dialogue between Christian minorities and Muslim-majority governments, reducing radicalisation risk.

His approach aligns with the Vatican’s post–Cold War strategy: preventive diplomacy aimed at reducing the drivers of conflict before military escalation occurs.

Soft Power and Strategic Influence

The Vatican’s influence in military and diplomatic affairs has been mostly moral and symbolic rather than coercive. The Holy See is unique as a sovereign entity whose power derives entirely from ideas, networks, and spiritual authority. Ambassador Francis Rooney, a U.S. envoy to the Vatican, described this as the Vatican’s “power of convening” – a “soft power” based on its fundamental principles. Indeed, Benedict XV and John XXIII appealed directly to conscience; Paul VI and John Paul II brokered with courage rather than cannons; Francis continues to bring parties to prayer before negotiation.

Analysts note that Vatican diplomacy often succeeds by adding value rather than imposing solutions. As Rooney put it, the Holy See can gather hostile parties in prayer or negotiation when others have failed. Its vast diplomatic network, over 180 nunciatures worldwide, allows it to be present even where other states are absent. The “peace algorithm” envisioned by Francis – building trust through small gestures like child exchanges and humanitarian aid, and shared values – exemplifies this approach. In an age of great power rivalry, the Vatican’s neutrality and moral voice allow it to serve as a mediator. By not seeking territory or wealth, the Holy See maintains goodwill.

However, Vatican influence has limits. Structural political and military factors usually dominate conflict outcomes. For example, Benedict XV could not stop WWI’s devastation, nor did Pope Paul prevent Vietnam’s escalation. Pius XII’s knowledge of genocide could not force Hitler’s hand. John Paul II’s support for Solidarity helped topple communism, but economic and geopolitical strains were also crucial. When Vatican ideas clash with great power interests, the popes have had to settle for moral suasion or symbolic statements. In many cases, they acted as agenda-setters rather than deal-makers: their pronouncements, like populorum progression and invocation of nuclear peace, have helped shape international norms, like the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty’s ethos, even if enforcement lay elsewhere.

The Holy See exemplifies normative power – wielding influence through ideas and legitimacy. In IR terms, the Vatican’s “soft power” comes from its global cultural reach and moral consistency. It relies on framing conflicts as ethical dilemmas. Think tanks note that while the Vatican accepts certain strategic realities, like it once tacitly accepted nuclear deterrence as a lesser evil, it consistently urges a culture of peace. It often links peace with development and justice, pushing for “just a peace” that addresses root grievances.

Where has papal diplomacy mattered? The record suggests two domains:

- 1. Conflict mediation: The Holy See has successfully mediated or contributed to ending wars such as Chile–Argentina (1984) and has been invoked by civil wars like South Sudan (2020).

- 2. Shaping decisions indirectly: By influencing populations and leaders through moral authority. For example, John Paul II’s presence in Poland is credited with emboldening citizens and officials to resist Soviet control. By contrast, moments like Benedict’s 1942 silence or Paul’s Vietnam appeals show where Vatican influence was minimal.

The papacy’s military-diplomatic role has been as a catalyst and moral conscience. It rarely has a seat at formal peace tables unless invited, but even then, it typically refrains from imposing terms. Its power lies in being a “reminder” of higher values and in offering itself as an honest broker. Academics would classify this as playing on the normative layer of international politics rather than the material. The Vatican often urges respect for international law and human rights, aligning with broader global norms. In nuclear diplomacy, popes have consistently called for disarmament and “no first use” policies, like John XXIII’s Pacem in Terris and Benedict’s statements on nuclear testing, reinforcing moral caution. Yet they have had to tolerate deterrence as a practical reality, even if reluctantly.

Where the papacy’s influence is symbolic or constrained, complex power struggles usually demand material leverage, military and economic pressure, which the Vatican lacks. During the Cold War, for instance, the Holy See could not dictate Soviet policy despite Ostpolitik. After 9/11, it could condemn terrorism but could not coerce actors. At times, its moral stands have even been contested. Some secular leaders grumble at spiritualising politics. But by tradition, the Vatican does not claim a direct political mandate.

But even symbolic gestures are significant. For war-weary populations, a Pope’s comfort, like blessing the wounded and addressing crowds at a bomb site, can cement peacebuilding at the grassroots level. And where a government cares about Catholic opinion, like in deeply Catholic countries, papal positions can sway policy. Historians credit the Vatican’s discreet diplomacy in securing hostage releases, like in Lebanon in the 1980s, and defusing sectarian strife, though these actions often remain confidential.

The Holy See’s strategic role is not as a decision-maker in war plans, but as a persistent advocate for peace. It excels in humanising conflicts and offering moral incentives for dialogue. Its contributions have ranged from direct mediation, like with Chile–Argentina and South Sudan, to rhetorical influence, like with the Cuban Crisis and appeals for Ukraine’s peace. While the Vatican seldom drives outcomes, it can shape the environment in which outcomes are decided.

Read More:

- War on the Rocks: The Vatican’s Nuclear Diplomacy from the Cold War to the Present

- Crisis Magazine: A War Prevented: Pope John XXIII and the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Vatican News: 12 October 1962: John XXIII’s appeal to States to heed “anguished cry for peace”

- Vatican News: Pope: ‘Dialogue prevented war between Chile and Argentina 40 years ago’

- Vatican News: South Sudan leaders: ‘How can we not bring peace if the Pope pushes us to do so?’

- Inside the Vatican: The Soft Power of Vatican Diplomacy is as necessary as ever

- El Pais (english): Pope offers to mediate in Colombia’s rocky peace talks with FARC rebels

- Washington Post: Vatican Pope Pius Records Holocaust

- The Guardian: The Vatican’s silent concord

- NCR Online: World War I’s Pope Benedict XV and the pursuit of peace

- Vatican News: Pope welcomes Ukrainian President Zelensky to Vatican for third time

- Reuters: Pope Leo Heading to Turkey

- Reuters: Pope says Ukraine should have ‘courage of the white flag’ of negotiations

- Reuters: Pope Ends First Overseas Trip by Praying with 100.000 Lebanese

- Reuters: Pope Leo Taking Peace Message to Lebanon

- Reuters: Pope Leo Meets Middle East Christian Leaders

- National Catholic Register: Pope Leo’s First Apostolic Journey Delivers Real-World Results

- Al Jazeera: Pope Leo urges unity on day two of Lebanon visit

- Inside the Vatican: Pope Francis and the peace algorithm

- Inside the Vatican: The Soft Power of Vatican Diplomacy is as Necessary as ever

- El País: Pope offers to mediate in Colombia’s rocky peace talks with FARC rebels

- Vatican News: South Sudan leaders: ‘How can we not bring peace if the Pope pushes us to do so?’

- Radio Free Europe: Islam: Pope’s Remarks Bring Interfaith Dialogue To Crisis Point

- Vatican News: Pope: ‘Dialogue prevented war between Chile and Argentina 40 years ago’

- Office of the Historian: 42. Editorial Note

- Vatican Archives: Papal diplomatic documents

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Benedict XV

- Vatican: Peace Note of 1917

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Pius XII

- Yad Vashem: Rescue of Children

- JFK Library: Crisis documents

- Vatican: Pacem in Terris

- UN: Paul VI UN Address (1965)

- National Security Archive: Vatican and Eastern Bloc files

- New York Times: Gorbachev on John Paul II

- BBC: Beagle Channel mediation

- Politico: Papal peace messages in Lebanon