When the last US troops left Afghanistan in August 2021, Washington said it was ending a war, not abandoning a country. In practice, it did both. And in doing so, tilted the region toward Chinese influence. Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland had all spent two decades backing the NATO-led operation in Afghanistan, politically, militarily, and at human cost.

For two decades, the Nordics helped the US prosecute, legitimise, and sustain a war that ended in a chaotic exit and the Taliban back in charge. Denmark paid the highest price among them, in a way that was visible to every Danish family and every NATO planner. Afghanistan was run through two main NATO frames: ISAF (2001–2014), then the training-and-advising mission Resolute Support (2015–2021).

Denmark (NATO)

- Years: 2002–2021 (ISAF + later Resolute Support).

- Scale: about 18,000 deployed across the war; peak ~760 in Helmand.

- Role: Hard combat, especially Helmand Province, closely tied to British and US operations — the kind of deployment that buys alliance credit, but also racks up casualties fast.

- Fatalities: 43 Danish service members killed in Afghanistan.

Denmark’s Afghan record is exactly the Good Ally story Washington usually demands from small states.

Norway (NATO)

- Years: Dec 2001 – Aug 2021.

- Scale: around 9,200 Norwegian personnel served over 20 years.

- Role: a mix of NATO/coalition tasks, including stabilisation and support roles; Norway also cycled substantial numbers through the theatre over time rather than running one giant permanent footprint.

- Fatalities: 10 killed while serving in Afghanistan.

Sweden (partner, not NATO at the time)

- Years: major participation 2002–2014 (ISAF); the last Swedish troops returned in May 2021 as the international mission closed.

- Scale: more than 8,000 deployed soldiers (ISAF period).

- Role: largely in northern Afghanistan, including Provincial Reconstruction Team work and security tasks that still carried real risk.

- Fatalities: 5 Swedish soldiers killed in action. At least one more Swede died while working for “international organisations”.

Finland (partner, not NATO at the time)

- Years: 2002–2021 (ISAF + Resolute Support; Finland joined RSM from the start in 2015).

- Scale: about 2,500 Finnish soldiers served (official Finnish statements also cite 2,466 across ISAF/RSM).

- Role: advisory, training, command/support functions; much of the Finnish deployment operated alongside Swedish-led structures in the north.

- Fatalities: 2 killed; 15 wounded (ISAF-era casualties).

Aftermath: Race for Natural Recourses

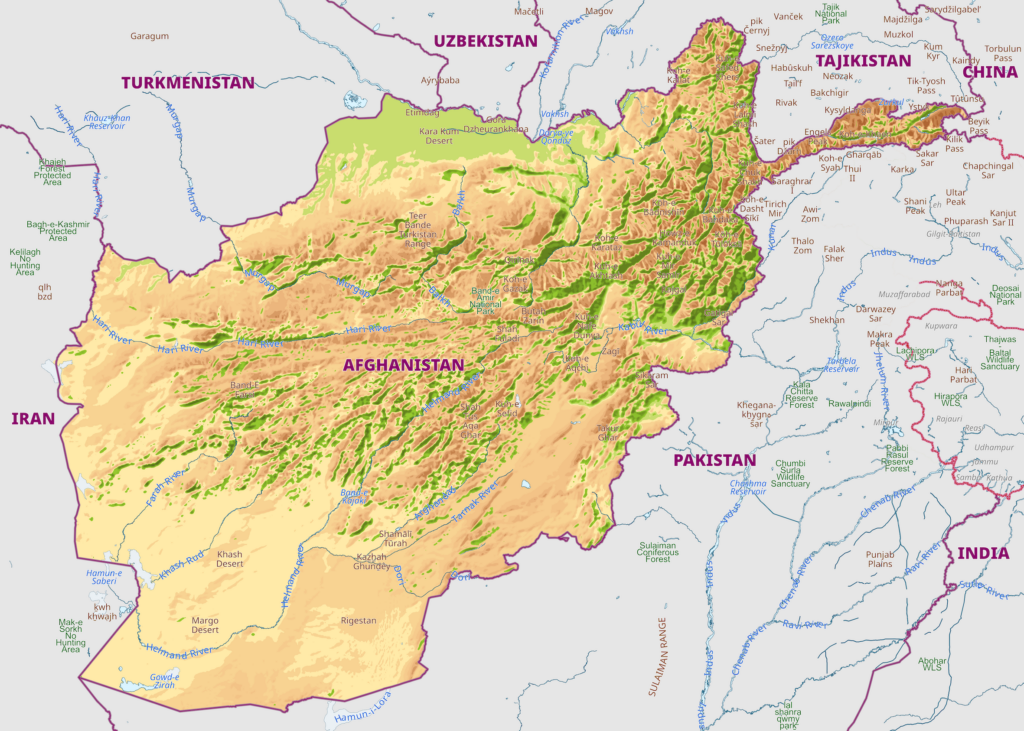

After the withdrawal of US and NATO troops from Afghanistan, the power struggle in the region has increasingly centred on the country’s natural resources. Afghanistan’s mineral wealth is vast and largely untouched. The country is estimated to hold around 2.2 billion tonnes of iron ore, 60 million tonnes of copper, 183 million tonnes of aluminium, and significant deposits of rare earth elements, including lanthanum, cerium, and neodymium. At a time when access to such materials has become a matter of national security, control over mineral supply chains has turned into a geopolitical contest. China currently holds the upper hand, while the United States, the European Union, and other powers are scrambling to build and protect alternative, independent sources of critical minerals.

China did not replace the United States militarily. It did something more Chinese: it kept its embassy open, talked to whoever held power, dangled trade and projects, and went hunting for resources that matter to Beijing’s supply chains.

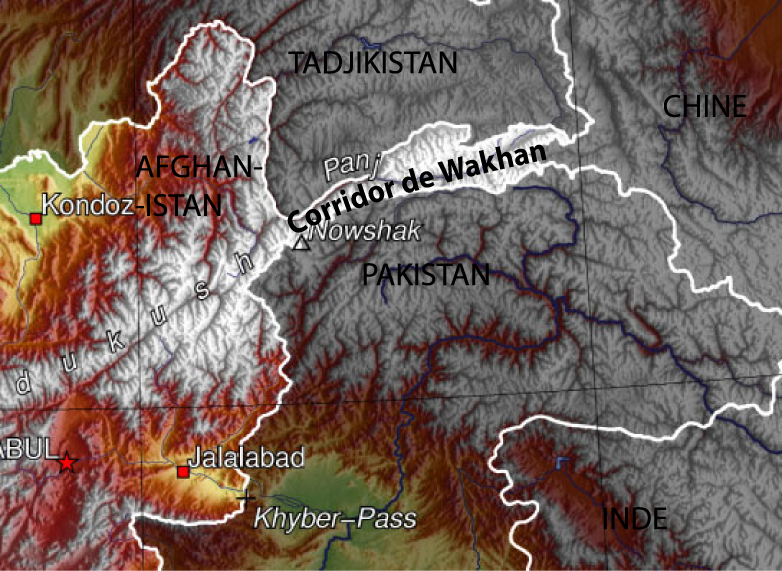

Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor to China

Afghanistan is wedged between nuclear-armed Pakistan, Iran, and the former Soviet space, and it touches China via the narrow Wakhan Corridor. That makes it a security problem even for states that swear they want nothing to do with Afghan politics. If Afghanistan exports instability, it does not travel by plane. It leaks overland.

For Beijing, the nightmare is not American troops returning. It is militant networks using Afghan terrain and Taliban-era permissiveness to threaten China’s western periphery, Chinese projects in the region, or Chinese nationals working under weak protection. China’s diplomacy with the Taliban has consistently mixed economics with demands, explicit or implied, about Security Guarantees.

Mining as the New Cash Cow

The withdrawal removed America’s local military footprint, its day-to-day leverage over Afghan security forces, and much of its visibility on the ground. That matters because Afghanistan under the Taliban is not merely authoritarian. It is commercially chaotic and violently contested in patches. The result is a country where big-ticket extraction projects can be announced with fanfare. and then stalled, cancelled, attacked, or quietly looted.

The Taliban, cut off from much Western aid and recognition, turned to Cash Cow sectors such as mining to fund the state. The pitch to outsiders is blunt: bring capital, take minerals, pay royalties, and don’t ask awkward questions.

China’s Hunt for Mining

China’s advantage after 2021 was political access, not a magical new mineral map. The major Chinese-linked resource plays in Afghanistan mostly predate the Taliban takeover, notably the Mes Aynak copper concession, won in the 2000s, and earlier oil interests in the north. What changed after the US exit was that the Taliban needed partners and cash urgently, and China was willing to engage without recognition, elections, or human-rights conditions.

Post-withdrawal China Resource Moves:

- Amu Darya oil deal (signed 2023): The Taliban signed a major oil extraction agreement with a Chinese company, widely reported as the first big international extraction deal of the Taliban era. Reuters described it as a contract to extract oil from the Amu Darya basin.

But the “win” proved fragile: reporting in 2025 described the collapse/termination of the arrangement amid mutual accusations and poor performance. That is Afghanistan in one paragraph: deal announced, reality bites. - Mes Aynak copper: from dead project to guarded revival (2024): After roughly 16 years of delays, work was publicly re-launched with ceremonies and heavy Taliban security around equipment — a symbolic moment showing the Taliban’s push to monetise minerals and China’s willingness to re-engage.

This was not a “new” Chinese conquest; it was a long-stalled Chinese bet being revived under a new regime because the regime was desperate and China still wanted the ore. - Mining contracts and the Taliban’s auction-state approach (2023 onward): The Taliban announced multibillion-dollar mining contracts with local firms often tied to foreign partners, including China. Independent monitoring suggests a rapid expansion in the number of mining arrangements under Taliban rule.

- Diplomatic-economic deepening (2024–2025): China offered Afghanistan tariff-free access for Afghan goods and kept signalling that mining cooperation was on the table; Reuters also reported Taliban statements that China wanted to initiate practical mining activity and encouraged Afghanistan to join the Belt and Road Initiative.

China gained room to operate economically after the US left, and mining was central to the courtship. But it is not a clean story of Chinese Extraction Triumph. It is a story of high ambition meeting Afghan insecurity and weak governance.

China Wants Critical Minerals

Beijing’s interest is shaped by modern industrial warfare and modern industrial policy: batteries, electronics, aerospace, precision weapons, and the basic metals of infrastructure.

Afghanistan’s resource base includes copper, iron, gold, rare earth elements, lithium, and other critical minerals, documented in USGS assessments conducted with Afghan partners.

On the specific point you raised, cobalt, USGS work explicitly covers an “Aynak copper, cobalt, and chromium” area of interest, illustrating why cobalt appears in strategic discussions tied to Afghan geology. China’s strategic rationale is simple: if you can lock in diversified supply or future options, you reduce vulnerability to sanctions, chokepoints, and Western-controlled markets. Afghanistan is attractive precisely because it is underdeveloped: the minerals are not yet locked up by established global majors, and the Taliban will sign almost anything that brings cash and a headline.

Security, Legitimacy and Local Anger

If there is a single theme in China’s Afghanistan engagement, it is this: China wants resources without owning the security problem. In January 2026, clashes around a gold mining operation in Takhar province left people dead and forced the suspension of operations during an investigation.

In January 2025, Afghan officials reported the killing of a Chinese national working for a mining company in the northeast, another reminder that foreigners remain targets and that Taliban protection is inconsistent.

This is also why some China-Taliban Deals look more like diplomatic theatre than bankable projects: ceremonies are cheap; roads, refineries, security perimeters, and long-term community consent are expensive.

Read More:

- Reuters: China, Afghanistan hold talks on mining, belt and road participation

- Reuters: China to offer Taliban tariff-free trade as it inches closer to isolated resource-rich regime

- Reuters: Afghanistan’s Taliban administration in oil extraction deal with Chinese company

- Associated Press: Clashes between residents and gold mining company kill 4 in Afghanistan

- Associated Press: The Taliban say a Chinese national has been killed in northeastern Afghanistan

- RFE/RL (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty): China Breaks Ground On Massive Afghan Copper Mine After 16 Years Of Delays

- The Diplomat: A New Dawn for Afghanistan’s Mes Aynak Copper Mine?

- NPR / WBHM: Contract breach or banditry? Inside the collapse of the Taliban’s oil deal with China

- The Diplomat: Taliban End Chinese Oil Field Contract in Afghanistan

- SIPRI: China’s Footprint in a Taliban-led Afghanistan (PDF)

- Wilson Center: Mining for Influence: China’s Mineral Ambitions in Taliban-led Afghanistan

- USGS: Summary of the Aynak Copper, Cobalt, and Chromium Area of Interest (PDF)

- USGS: Summaries of Important Areas for Mineral Investment and Production Opportunities in Afghanistan

- Reuters: China, Afghanistan hold talks on mining, Belt and Road participation

- Reuters: Tajikistan says five people have been killed in cross-border attacks

- SpecialEurasia: Afghanistan: the Killing of a Chinese Worker Might Compromise the Sino-Taliban Relations

- Amu TV: Afghanistan: Protests over gold mining flare again in Takhar

- Global Initiative: Why is Afghanistan part of the great extractives race?

- Wikipedia: Afghanistan (mineral wealth overview)

- Wikipedia: Wakhan Corridor