Denmark is dramatically boosting its Arctic surveillance capabilities by purchasing four over-the-horizon unmanned drones. Norway has also been studying long-range drones for its High North, eyeing the MQ-9B and other platforms for Arctic surveillance. This is a significant upgrade of NATO’s eyes in the Far North.

In July 2025, Copenhagen signed an agreement via NATO’s procurement agency to acquire four MQ-9B SkyGuardian UAVs from the U.S. firm General Atomics. These long-endurance drones will equip the Danish Armed Forces to monitor the vast, remote areas of the Kingdom of Denmark – including Greenland and the Faroe Islands – with advanced signals and imagery intelligence. Danish officials say the drones will fill critical gaps in Arctic awareness, enabling faster reaction times even in far-flung locales. “With the purchase of four long-range drones, we are strengthening both Danish and European security,” Defence Minister Troels Lund Poulsen said, calling it a “crucial step” towards Europe doing more for its own defence. The drones are financed through Denmark’s new defence agreements (2024–2033) and Acceleration Fund, which specifically target readiness in the Arctic and North Atlantic. Initial plans to buy two drones, approved in 2021, were doubled to four in 2025 amid rising threats, and deliveries are expected by 2028. Neighbouring Norway may soon follow suit – Oslo has been studying long-range drones for its High North, eyeing the MQ-9B and other platforms for Arctic surveillance.

Denmark’s investment in over-the-horizon drones marks a significant upgrade of NATO’s eyes in the Far North, at a time when arctic security is firmly in focus.

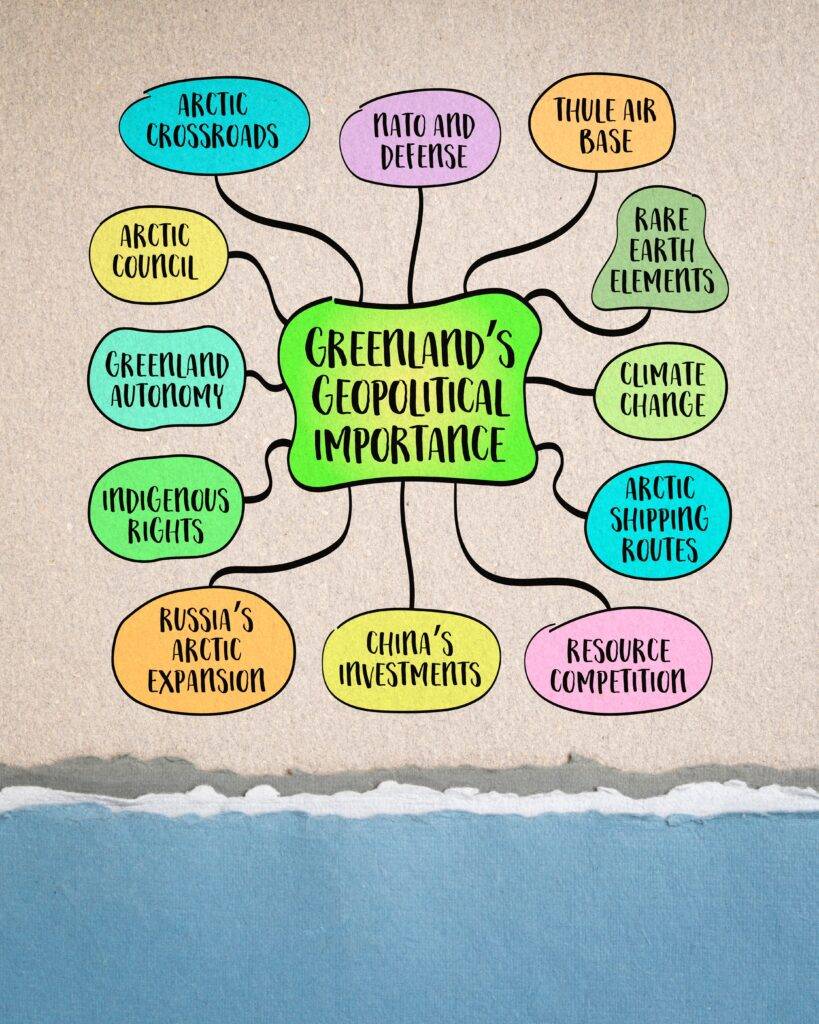

Greenland Is Not for Sale

This Danish military buildup comes against a backdrop of U.S. pressure regarding Greenland, the semi-autonomous Danish territory rich in strategic value. In early 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump renewed his unusual interest in controlling Greenland, bluntly asserting that Greenland is vital to U.S. security and suggesting Denmark should cede the island. Such remarks – including Trump’s earlier musings about “buying” Greenland – alarmed Danish and Greenlandic leaders, who insisted their land is not for sale. Denmark’s response has been two-fold: diplomatically deflecting Washington’s advances, while pouring new resources into Greenland’s defence to show it takes Arctic security seriously. In January 2025, Copenhagen announced a 14.6 billion DKK ($2.1 B) Arctic military investment plan explicitly framed as answering Trump’s pressure. The deal funds three new Arctic patrol vessels, to be built domestically, doubles the drone fleet from two to four, and expands satellite surveillance over Greenland. This surge comes after decades of underfunding that left Greenland a “security black hole” with only four aging patrol ships, one surveillance plane and a handful of dog-sled ranger patrols covering an island four times the size of France.

Danish leaders have also strengthened ties with the U.S. on their own terms. In June 2025, the Danish Parliament approved a landmark agreement to allow U.S. military bases on Danish soil – a move widening an earlier pact that already granted U.S. forces broad access to Danish airbases. The timing was telling: it came just as Washington’s Arctic ambitions grew more brazen. Denmark inserted a sovereignty clause allowing it to cancel the deal if the U.S. attempted to annex any part of Greenland, underscoring Danish resolve to guard its realm. Greenland’s Prime Minister bluntly criticised U.S. rhetoric as “disrespectful,” vowing the island “will never, ever be a piece of property that can be bought by just anyone”. Meanwhile, Denmark’s military has staged its largest Greenland exercises since the Cold War, deploying fighter jets, a frigate, special forces and troops on the island in mid-2025. These drills, aimed at deterrence and rapid response, reflect Copenhagen’s determination to show both allies and adversaries that it can defend Greenland’s critical points. Major General Søren Andersen, head of Denmark’s Arctic Command, even quipped that the prospect of a U.S. “takeover” of Greenland isn’t keeping him up at night – “I sleep perfectly well,” he told Reuters, emphasising that Danish and American militaries “work together, as we always have”. Still, Andersen acknowledged the need for a “credible deterrent” against any aggression and welcomed repeating the high-profile Arctic drills going forward. European partners have rallied to Denmark’s side as well. In June 2025, French President Emmanuel Macron made a symbolic visit to Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, alongside Danish PM Mette Frederiksen, to express solidarity in the face of U.S. territorial musings. “The situation in Greenland is clearly a wake-up call for all Europeans… you’re not alone,” Macron told Greenlandic officials.

Days earlier, U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth had alarmed Europe by hinting at Pentagon “contingency plans” to seize Greenland by force if needed. This strategic backdrop spurred not just Denmark but also NATO allies to step up Arctic diplomacy and defence commitments. Iceland and France signed a new security cooperation pact focused on the Arctic, and other Nordic states have increased coordination on northern defence. In short, Trump’s Greenland pressure has prompted Denmark to walk a tightrope: reassuring Washington by investing more in Arctic security and even hosting U.S. assets, while reassuring Europe and Greenland that Danish sovereignty and Western cooperation will keep the Arctic out of unwanted hands.

Russian Militarisation in the High North

Denmark’s renewed focus on Arctic defence is also driven by Russia’s military build-up in the High North, which has accelerated tensions in the region. Unlike Europe’s previously modest Arctic posture, Russia has spent decades investing in Arctic bases, airfields, and ice-hardened military infrastructure along its vast polar frontier. Moscow’s Northern Fleet prowls the Arctic Ocean, and new radar stations and missile sites dot Russia’s Arctic coast – all part of the Kremlin’s bid to dominate emerging polar sea lanes and defend its resource-rich Far North. The stark disparity was acknowledged by Denmark’s defence chief: “Russia has spent decades investing in Arctic security… European countries have only recently begun investing significantly in northern defence”. Indeed, it took Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine to truly jolt NATO and Nordic nations into recognising the Arctic as a frontline of strategic concern. Since then, keeping the North Atlantic and Arctic Sea lanes secure – from the GIUK gap between Greenland, Iceland and the UK, to the fjords of Norway – has become a top-tier NATO priority. Greenland, sitting astride the great circle route between North America and Europe, is integral to this: the U.S. Pituffik Space Base (Thule) in northwest Greenland hosts vital early-warning radars and space surveillance systems guarding against missile threats. Yet until recently, Greenland’s sparse surveillance made it a tempting blind spot for any hostile incursion. Western officials have warned that Russian naval vessels and even Chinese research ships have appeared unexpectedly in Greenland’s vicinity in the past, testing the waters of Danish vigilance.

Denmark is now trying to erase that notion of an undefended Arctic flank. Its new drones, ships and radar coverage in Greenland and the Faroe Islands aim to ensure no unwelcome aircraft or vessels go unnoticed in NATO’s northern gateway. “In reality, Greenland is not that difficult to defend – relatively few points need defending, and of course we have a plan for that. NATO has a plan for that,” said Maj. Gen. Andersen, projecting confidence that a small but smartly-equipped force can deter adversaries. As part of recent exercises, Denmark even forward-deployed F-16 fighter jets and a frigate to Greenland, signalling that it can surge firepower to the Arctic when needed. Andersen noted that if an enemy (for instance, Russia) attempted a landing on Greenland’s remote coast, the harsh environment and lack of infrastructure would likely “turn [their] military operation into a rescue mission” – a wry way to downplay the threat. Still, he and other NATO commanders insist that vigilance must increase: “To keep this area conflict-free, we have to do more, we need a credible deterrent. If Russia starts to change its behaviour around Greenland, I have to be able to act,” Andersen told reporters.

Russia’s own behaviour suggests it is eyeing NATO’s new Arctic capabilities. In late July 2025, as Denmark inked its drone deal, Russia’s Northern Fleet staged a “July Storm” combat drill in the Barents Sea – complete with fighter jets practicing intercepts of long-range drones. Russian Su-33 naval fighters launched air-to-air missiles at mock drone targets over the Barents, explicitly simulating “incoming enemy drones” as part of the exercise. The Barents Sea lies on NATO’s Arctic flank, and Russia’s drill was clearly a signal that it is training to detect and shoot down NATO surveillance drones in the High North. Notably, the Russian exercise came as NATO countries are rolling out new Arctic UAVs: a NATO RQ-4 Global Hawk conducted its first overflight of Finland in 2023, and a dedicated drone base for Alliance forces is being established at Andøya in northern Norway. Denmark’s MQ-9B drones will also operate in this evolving Arctic airspace. The cat-and-mouse dynamic is reminiscent of the Cold War, but now unmanned aircraft and long-range sensors are at the forefront. In sum, Russia’s military build-up and aggressive exercises underscore why Denmark and its allies are racing to plug gaps in Arctic defence – it’s a classic security dilemma playing out on the roof of the world.

China’s Rising Arctic Ambitions

Another driver of Denmark’s Arctic strategy is the rising ambitions of China in the far north. Though China has no Arctic territory, it has proclaimed itself a “near-Arctic state” and launched a Polar Silk Road initiative, seeking faster trade routes through melting polar seas and a foothold in Arctic affairs. Beijing’s expanding presence has been largely economic and scientific – icebreaker expeditions, research stations, investments in energy projects – but it carries strategic overtones that put Western nations on guard. Western sanctions isolating Russia have pushed Moscow to welcome Chinese capital and technology in Arctic ventures, from Siberian LNG plants to mining, knitting China and Russia closer in the region. For Denmark, the most immediate concern is Chinese interest in Greenland, which holds coveted rare earth minerals and other resources. In past years, Chinese state-linked companies have attempted to invest in Greenlandic mining projects and even infrastructure like airports, raising alarms in Copenhagen and Washington. Chinese scientific vessels have also made unsolicited forays near Greenland’s waters, fuelling suspicions about dual-purpose activities. The Trump administration openly accused Denmark of failing to keep China, and Russia, “out” of Greenland, a charge Denmark disputed but took seriously. In 2020, the U.S. responded by reopening its consulate in Nuuk and offering economic aid to Greenland, explicitly to counter China’s influence. This big-power courting of Greenland has only intensified the territory’s geopolitical value – and Denmark’s resolve not to lose grip.

Much of the great-power jostling comes down to strategic resources. The Arctic is believed to hold 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30% of its gas, but in recent years critical minerals have overtaken hydrocarbons as the prize. Greenland, in particular, sits on a treasure trove of rare earth elements (REEs) – metals essential for high-tech industries, from precision-guided missiles and fighter jets to smartphones and wind turbines. China dominates global rare earth supply chains, and it has not hesitated to use that leverage. In April 2025, Beijing imposed export controls on seven types of heavy rare earth elements – like dysprosium, terbium, and yttrium – which are crucial for military-grade permanent magnets. This followed earlier Chinese export bans on other minerals like gallium, germanium and graphite, all of which rattled Western industries. The message was clear: if geopolitical tensions rise, China can choke off materials vital to Western defence and green technologies. That prospect has sent policy-makers scrambling for alternative sources, and Greenland looms large in those plans. The island’s mineral endowment uncannily aligns with the very metals under Chinese restriction. For example, Greenland’s Kvanefjeld (Kuannersuit) deposit is estimated to contain over 11 million tonnes of rare earth oxides – including significant quantities of the heavy REEs that China is limiting. Other Greenland sites like Tanbreez also hold vast rare earth riches, while projects at Amitsoq offer high-grade graphite and the Malmbjerg site contains one of the world’s largest molybdenum reserves. In June 2025, Greenland’s government granted a 30-year mining license for Malmbjerg, a molybdenum project backed by the European Union, which could supply 25% of Europe’s molybdenum needs. Notably, China had just tightened export controls on molybdenum products as well, in retaliation for U.S. trade measures.

Western nations are now racing to turn Greenland’s mineral promise into tangible production – a task easier said than done. Greenland’s mining sector has been slow to develop, hampered by harsh terrain, sparse infrastructure and regulatory hurdles. But the strategic urgency is spurring action. The EU has made Greenland a focal point of its Critical Raw Materials Alliance, and the U.S. government’s export-import bank is considering a $120 million loan to jump-start a major rare earth mine on the island. Greenland’s authorities, for their part, are keen to diversify away from fishing and Danish subsidies; they have urged the U.S. and Europe to invest in Greenlandic minerals “or else” risk losing out to China. It is a new Great Game over Arctic resources, and rare earths are at its heart. Other northern European countries are also in play: in 2023, Sweden announced discovery of Europe’s largest rare earth deposit – over 1 million tonnes of REO in Kiruna – which, if mined a decade from now, could reduce Europe’s dependence on Chinese imports. Finland and Norway likewise are exploring graphite, phosphate and REE projects in their Arctic territories. However, finding the ores is just one battle – processing them is another. Currently, Europe lacks full-scale facilities to refine rare earths into high-purity products, a gap that leaves even European-mined material often heading to China for refining. This uncomfortable reality has NATO and EU strategists convinced that secure access to Arctic minerals is a security imperative. In the long run, controlling the supply of critical minerals will impact the defence supply chain as much as controlling territory. Denmark’s heightened interest in Greenland’s mining future can thus be seen as part of a larger effort by Western allies to break China’s stranglehold on critical materials. The battle for the Arctic is not only about bombers and bases, but also about who will supply the world’s cobalt, rare earths, and lithium in the 21st century.

Who Benefits from Denmark’s Arctic Defence Investments?

Denmark’s Arctic defence splurge will reverberate not just geopolitically but also in the realm of industry and commerce. A handful of companies and countries stand poised to benefit from Copenhagen’s spending. First and foremost is the American defence industry, given that Denmark’s marquee purchase – the four MQ-9B drones – comes from General Atomics in California. The contract value hasn’t been disclosed, but it undoubtedly represents hundreds of millions of dollars in high-tech hardware and support. By choosing a U.S.-made platform, via a NATO procurement framework, Denmark is effectively sending business to a key ally’s firms. This aligns with a broader pattern: many European militaries, under pressure to ramp up readiness, are turning to proven American systems that can be fielded relatively quickly. In Denmark’s case, the urgency to monitor Greenland’s skies – and perhaps a nod to American expectations – tilted the decision towards the Battle-tested MQ-9 Reaper family instead of waiting for a European-developed drone that might be years away. The U.S. government is likely quietly pleased. Not only will American-made drones bolster Arctic security for NATO, but they also integrate smoothly with U.S. Arctic Command assets. It’s a synergy of strategic and industrial interests. There may also have been an element of realpolitik: facing Trump’s Greenland demands, investing in U.S. kit could be Denmark’s way of showing Washington that “we’re taking Arctic defence seriously – and we’re doing it with your technology.” In other words, Denmark gets capability, the U.S. gets both a more secure northern flank and a lucrative sale.

Denmark has been careful to ensure its Arctic buildup isn’t solely an import spree – it also boosts domestic and European industry. The plan to build three new Arctic-capable naval vessels is a boon for Danish shipbuilding. A national consortium named Danske Flådeskibe K/S (Danish Naval Ships) has been established, bringing together Denmark’s largest defence company Terma, naval design firm Odense Maritime Technology (OMT), engineering group Semco Maritime, and a major pension investment fund. This team was already contracted in 2023 to do the front-end design for the new patrol ships, and it now stands ready to construct and outfit the vessels entirely in-country. The consortium emphasises that Danish production is the fastest way to deliver capacity and will secure high-tech jobs at home. By building locally, Denmark keeps full control over the process and develops national expertise in Arctic ship technology – a smart move considering these ships must operate in polar conditions and perhaps support NATO allies. The first of the ice-strengthened patrol ships is expected by 2029. They are likely to carry Danish-made systems (Terma produces naval radars, communications, and electronic warfare gear) and potentially European weaponry. For example, Denmark could arm them with Norwegian Naval Strike Missiles or European SAMs, which would spread the benefit to other NATO suppliers. In short, Danish industry will reap the rewards of Arctic rearmament alongside U.S. contractors.

Other players set to benefit include those involved in surveillance and space assets. Denmark’s defence agreements mention investing in satellite coverage for the Arctic, which could mean purchasing services from commercial satellite imagery firms or collaborating with allies’ space programmes. Companies providing polar-orbit satellites, reconnaissance imagery, or communications in high latitudes may see new Danish contracts. For instance, Canada and Europe have Arctic observation satellites – RADARSAT and Copernicus programs – that Denmark might leverage, potentially channelling funds to those projects. Additionally, the new air defence radar in the Faroe Islands – part of Denmark’s Arctic push – likely involves a major radar manufacturer. While details are scant, such a system might be supplied by a Western defence firm – perhaps Lockheed Martin or Thales – and would need installation and maintenance, benefitting contractors and the local Faroese economy. Even Greenland’s mining sector stands to gain indirectly from defence-driven attention: Western mining companies and investors are now politically supported in Greenland as never before. Firms from Canada, Australia, and Europe developing Greenlandic mines have newfound backing – loans, fast-tracked permits – thanks to the geopolitical premium on Arctic resources. That means potential export revenue and local jobs in Greenland – a civilian complement to the military investment.

Geopolitically, the United States and NATO allies benefit strategically from Denmark’s spending. A more secure Greenland and North Atlantic reduce the burden on U.S. forces and extend NATO’s surveillance network. At the same time, Denmark’s choices reflect a balance between American and European partners: buying U.S. drones to integrate with American systems but building warships at home with European partners to boost regional capacity. It’s both “transatlantic” and “Europe first” in the same package. This approach helps Copenhagen navigate its alliances shrewdly. By comparison, if Denmark had spurned American equipment in favour of waiting for an EU-developed drone, it might have pleased European industrialists but frustrated Washington’s Arctic hawks. Conversely, outsourcing everything to U.S. suppliers would have undercut Denmark’s own industry and EU defence ambitions. The chosen mix suggests technology and timing trumped politics – Denmark needed Arctic capabilities sooner rather than later, and that meant tapping U.S. tech, but it also ensured longer-term projects, like ships, strengthen its own industrial base.

Treating the Arctic as a Strategic Frontline

Denmark’s purchase of long-range drones and broader Arctic defence investments mark a historic turning point for the small Nordic nation with outsized responsibilities in the north. After years of benign neglect, Copenhagen is now treating the Arctic as a strategic frontline – one demanding modern surveillance, persistent presence, and close cooperation with allies. The catalyst has been a confluence of pressures: Russia’s military resurgence in the Arctic, China’s hunt for footholds and minerals, and even the unorthodox pressure from a close ally, the United States, eyeing Danish territory with transactional zeal. The result is that Greenland and the Arctic are no longer peripheral in Danish security planning; they are central. As Defence Minister Poulsen put it, “Europe must be able to do more itself” in the north. Denmark’s actions give weight to that statement – Europe is indeed stepping up, with Denmark in the vanguard, to ensure the Arctic remains stable and under friendly control.

Other Arctic and Nordic nations are watching closely and following suit. Norway has poured money into new Arctic patrol aircraft, submarines and is evaluating drones similar to Denmark’s. Canada – which faces its own Arctic surveillance gaps – has pledged to boost defence spending and modernise NORAD early-warning systems. Finland and Sweden, newly in NATO, bring valuable Arctic terrain and technology to the table, and they, too, are investing in northern forces. Even traditionally neutral Iceland is drafting its first security policy amid concerns over Arctic airspace and has invited more NATO activity on its soil. In essence, Denmark’s drone deal is one piece of a larger puzzle: a collective Western response to a fast-changing Arctic. The battle for the Arctic, as some call it, is not an outright conflict but a high-stakes competition to shape the future of a region opening up due to climate change and geopolitical shifts. In this contest, Denmark’s new drones will serve as sentinels – quietly patrolling the icy skies, extending NATO’s eyes and ears, and reinforcing that the Arctic’s tranquillity cannot be taken for granted. With minerals to secure, sea lanes to monitor, and great powers to deter, Denmark and its allies are in for the long haul in the High North. By investing now, Denmark aims to ensure that the Arctic remains a zone of cooperation among allies rather than a lawless frontier up for grabs. Greenland’s own leadership, their land “will never, ever be a piece of property” to be bargained away – and Denmark’s latest defence moves back that up with capability and commitment.

Read More:

- Breaking Defense: Denmark orders four MQ-9B SkyGuardian drones for Arctic missions

- Reuters: Denmark boosts Arctic defence spending by $2.1 billion, responding to US pressure

- Eye On the Arctic: Denmark to expand Arctic surveillance with purchase of long-range drones

- Eye On the Arctic: Danish general says he is not losing sleep over US plans for Greenland

- Eye On the Arctic: Denmark approves US military bases on Danish soil as Trump eyes Greenland

- Eye On the Arctic: Europeans step up Arctic diplomacy amid U.S. and global pressure

- Reuters: Greenland gives EU-backed critical metals project permit to mine

- Mining News North: From export bans to Arctic plans: Greenland’s mining opportunity

- Naval News: Danish consortium ready to build new Arctic patrol vessels and frigates

- ICAS: US, China and EU: The race for Greenland’s mineral riches

- Reuters: Sweden’s LKAB finds Europe’s biggest deposit of rare earth metals

- Mining.com: Greenland urges US, Europe to invest in its critical minerals, or China will

- Terma: DALO and Danske Patruljeskibe K/S reaches agreement on new naval vessels for The Danish Armed Forces

- Danske Flådeskibe: Danish consortium to build Arctic ships and new frigates in Esbjerg