The vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, over 5,000 nautical miles, has long been a protective buffer for the U.S. West Coast against any Asian naval threats. In a conflict with China, American strategists traditionally assumed that Chinese warships or submarines would struggle to project power across such distances. China’s development of extra-extra-large unmanned underwater vehicles (XXLUUVs) may upend that assumption.

These are essentially giant underwater drones – as large as conventional submarines, that operate without crews. By leveraging cutting-edge automation and power systems, they could give Beijing low-risk options to threaten ports and shipping on the U.S. West Coast, despite the tyranny of distance.

Submarines Without Crews

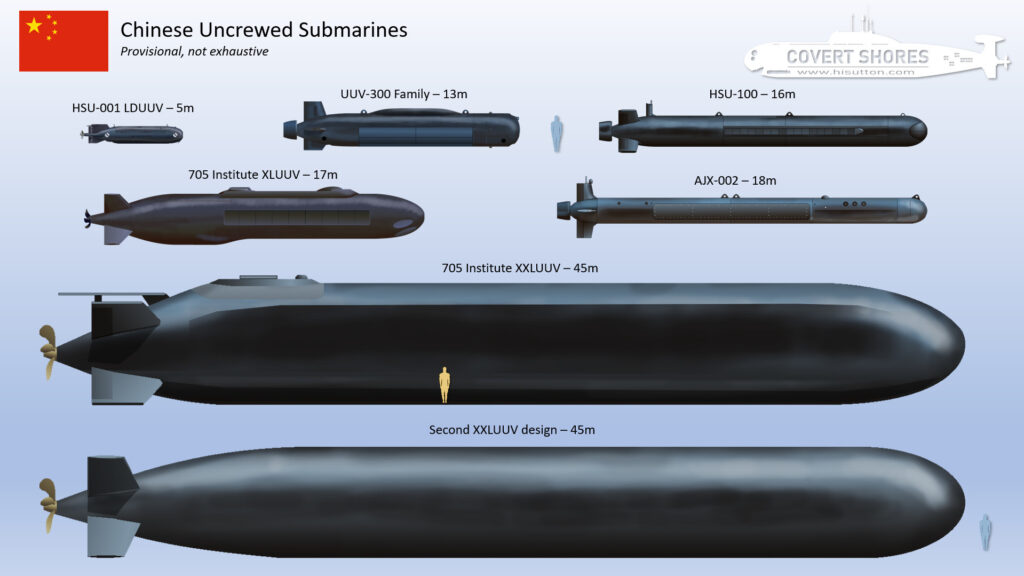

China is reportedly building the world’s largest underwater drones, with at least two different models under testing in the South China Sea. At over 40 meters long, these leviathan UUVs rival full-size attack submarines in scale, the Naval News reports. Unlike smaller autonomous submersibles, these giants are diesel-electric in design, much like a standard diesel submarine but without any crew compartment. A builder’s model displayed at a recent defence show revealed the basic layout: a diesel generator and an unusually large bank of batteries take up most of the hull, filling the space where crew quarters would be. This suggests China is prioritising endurance and range, trading crew accommodations for more fuel and batteries.

The model at the defence expo was shown carrying a formidable payload – torpedo tubes, naval mines, and even the capacity to launch smaller UUVs. In essence, these drone subs could perform many of the same missions as manned submarines: laying minefields, attacking ships, or deploying mini drones, all without risking a human crew. Making an underwater drone so large does come with challenges, like cost, construction time, maintenance and need for port facilities. Thus, the design must offer advantages to justify its size. Experts speculate the key benefits of an XXLUUV over smaller drones or crewed subs likely include:

- Larger payload and sensors: The XXL size allows carrying more weapons, such as torpedoes and mines, or larger sensor arrays, like towed sonar, for greater reach in detection.

- Much greater operational range: Without crew life-support limits, these drones can allocate more space to fuel and batteries, enabling far longer missions than conventional subs. Range is believed to be the decisive advantage of these designs.

Analysts estimate China’s new XXLUUVs will have an extraordinary range of roughly 10,000 nautical miles. This figure is based on specifications published for a similar concept sub unveiled by a Chinese shipbuilder, corroborated by rough calculations of the hull size. Such a range would put cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles well within reach of a launch from Chinese waters.

10,000 Nautical Miles Under the Sea

A closer look at the range breakdown illustrates how these unmanned subs achieve 10,000+ nm reach. According to the design data, the XXL drone could travel about 7,000 nm using its diesel engines while snorkelling, periodically running at periscope depth to air-breathe. This is on par with modern diesel-electric attack submarines. The game-changer is what comes next: an additional 3,000 nm of fully submerged travel on battery power alone. Thanks to a massive lithium-iron phosphate battery bank, the drone can sail roughly six times farther underwater than the best conventional diesel subs can on batteries. In practical terms, the drone could cross the final ocean gap to the U.S. coast entirely submerged, making it much harder to detect or intercept. This long-submerged sprint might be used in the terminal phase of a mission. For example, sneaking past anti-submarine patrols in the open Pacific or near U.S. shores.

Moreover, the 10,000 nm figure might be just a baseline. There are ways to extend the range even further: carrying extra diesel fuel, installing more (or higher-density) batteries, or even having a host ship tow the drone partway before release. The current prototype uses safer but slightly less energy-dense LiFePO4 batteries; simply switching to typical lithium-ion cells could nearly double the underwater endurance of 3,000 nm. In sum, with optimisation, the effective range could well exceed 10,000 nautical miles. It’s remarkable that these uncrewed platforms, no matter how expensive, can be considered “expendable”, meaning commanders might be willing to send them on one-way or high-risk missions that manned submarines would avoid. This opens up strategic possibilities that didn’t exist before.

From Coastal Defence to Pacific Power Projection

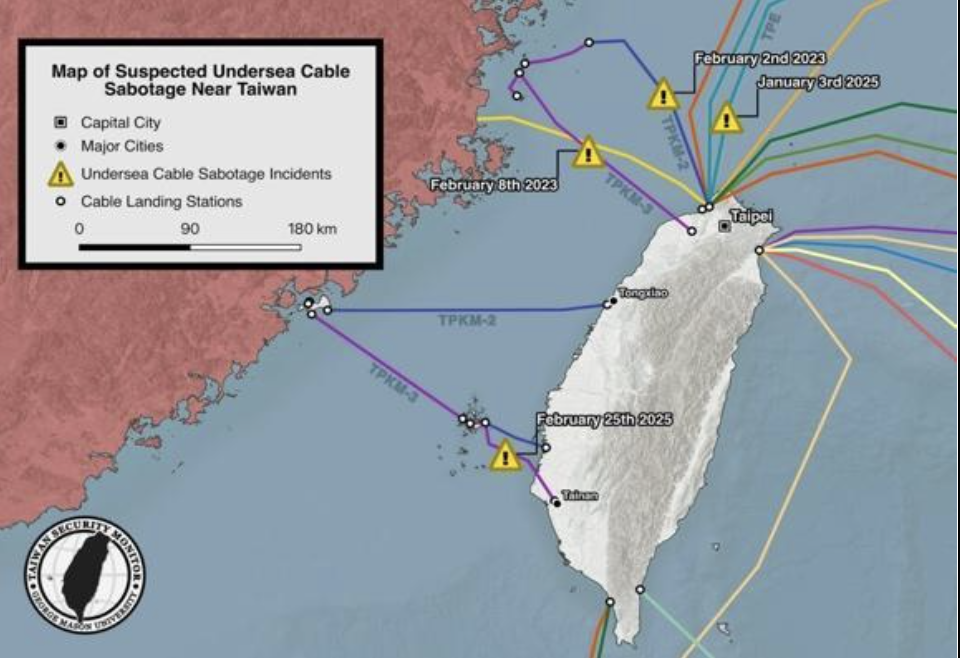

The deployment of long-range drone submarines suggests a significant shift in Chinese naval strategy, further from the South China Sea and Taiwan. Why is China investing in such far-reaching unmanned subs? Analysts believe these XXL UUVs could complement or even substitute for certain roles of China’s crewed submarine force. Lacking an onboard human decision-maker limits a drone’s flexibility and target discrimination to “straightforward” missions. For instance, an autonomous sub might be best suited to pre-defined tasks like minelaying in enemy waters, such as sowing the new deep-water mines China revealed recently, or attacking ships in a designated exclusion zone where anything that moves is presumed hostile. Fully autonomous lethal action is tricky, especially identifying friend or foe, but in a wartime scenario, these drones could patrol fixed kill zones or blockade routes without needing complex judgments.

One compelling mission that emerges is the ability to project power directly to American shores. With enough range to cross the Pacific, China’s XXLUUVs “could enable China to blockade the West Coast of the United States, or even the Panama Canal,” observes naval analyst H. I. Sutton in a Naval News interview. In theory, Beijing could dispatch a number of these unmanned subs to lurk outside major U.S. ports like San Diego, Los Angeles, or Seattle, in a conflict. Armed with mines or torpedoes, they could threaten shipping lanes, bottle up U.S. naval forces in port, or generally sow chaos – all while risking only robotic assets. This would represent a dramatic expansion of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)’s reach. Technically, China’s nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) already have the range on paper to operate off the U.S. West Coast, but so far, they do not venture into the Eastern Pacific. Likely, China has held them back because those few valuable SSNs are needed closer to home, and perhaps due to the risk of loss far from support. By contrast, a flotilla of cheaper, uncrewed XXL drones could be a risk-tolerant way to put pressure on distant targets. In effect, a quantity of expendable drones might achieve goals that high-value manned subs cannot, potentially changing how China fights and how it calculates risk.

It appears this program is more than just a technological experiment. Several indicators suggest China is serious about fielding these long-range UUVs, not just testing concepts. For one, the project has been shrouded in unusual secrecy – the drones are hidden in floating dry docks and tested from an obscure facility, rather than being proudly displayed as a mere R&D curiosity. Chinese shipyards often tout their prototype projects for attention, but in this case, they are keeping things under wraps. Secondly, China’s broader investment in large unmanned subs is booming: at a recent parade in Beijing, no fewer than eight large UUVs were showcased, five smaller AJX002 mine-laying drones and three HSU-100 UUVs, a fleet size other navies haven’t come close to in this category. Perhaps most telling, China is testing two distinct XXLUUV designs simultaneously at the same site. This implies a competitive evaluation is underway to select the best design – exactly how they developed the earlier generation XLUUVs that are now operational. All signs point to an accelerated development intended for deployment, not just theory.

China’s pursuit of these drones may also tie into another cutting-edge submarine project. Reports suggest China has built a unique prototype “Type 041 Zhou-class” submarine, which uses a small nuclear reactor to provide Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP), enabling it to cruise almost indefinitely at low speed without surfacing. This “nuclear AIP” concept addresses a similar challenge as the XXL drone, such as long underwater range and endurance, but with a human crew on board. It’s speculated that the expensive Zhou-class, of which only one is known, might be a parallel approach to extended-range undersea capability. The relationship between the two projects is unclear – the XXLUUVs might be a contingency plan if the Zhou-class tech doesn’t pan out, or vice versa. It’s equally possible they will complement each other, with crewed high-tech subs and numerous uncrewed drones together pushing the PLAN’s reach further into the Pacific. In any case, both developments underscore China’s determination to overcome the distance barrier and contest waters far from its shores.

Invasion Scares and Public Perception: From Hysteria to Hollywood

Whenever new military threats emerge, they don’t just challenge planners – they also capture the public’s imagination. The idea of foreign submarines or forces menacing the American homeland has a long history of provoking fear, fascination, and even dark humour in U.S. culture. The current alarm over Chinese drone subs recalls earlier eras when Americans contemplated enemy subs off their coasts – sometimes reacting with panic, and later, poking fun at that panic through satire.

Several films have lampooned or dramatised Americans’ responses to perceived invasion threats.

- The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966)

A satirical Cold War comedy that depicts the chaos in a small New England town when an inept Soviet submarine runs aground nearby. Local Americans, who know little about the outside world, erupt in paranoid panic at the thought of a Russian “invasion,” leading to absurd misunderstandings. The film cleverly mocks the hysteria and overreaction that characterized parts of the Cold War era. It was a critical and commercial success, indicating audiences were ready to laugh at their own fears. - 1941 (1979)

Directed by Steven Spielberg, this farce portrays the mass panic in Los Angeles after the Pearl Harbor attack when a Japanese submarine is rumoured to be offshore. Inspired loosely by real events, like the 1942 “Great Los Angeles Air Raid” false alarm and a Japanese sub’s minor shelling of California’s coast, 1941 exaggerates the bungling air-raid drills and trigger-happy defences into an over-the-top comedy. Starring John Belushi, the movie shows citizens and soldiers in Southern California literally firing at shadows in the sky, emphasizing how fear can turn to frenzy. While 1941 wasn’t Spielberg’s most successful film, it has since gained cult status as a zany caricature of home-front war jitters. - Red Dawn (1984)

In contrast to the above satires, this is a serious action thriller that imagines a World War III scenario: a surprise invasion of the United States by Soviet-led communist forces. A group of heartland American teenagers, the “Wolverines”, band together as guerrilla fighters after paratroopers descend on their town. Released at the height of Reagan-era Cold War tensions, Red Dawn tapped into genuine anxieties of the time, the fear of a Soviet attack or communist expansion in the Western Hemisphere. Starring Patrick Swayze, the film’s depiction of a beleaguered America being occupied inverted the usual Cold War script, where the U.S. was the superpower intervening abroad. It became a cultural touchstone, reinforcing a siege mentality and patriotism among some viewers, even as others saw it as exaggerated propaganda. The movie’s lasting popularity in military circles shows how powerfully fiction can shape perceptions of plausible threats. - Ghost Fleet (novel, 2015)

A recent techno-thriller that vividly envisions a near-future war with China, and eerily, it features some of the technologies we’ve discussed. In the story, a technologically advanced China, allied with Russia, launches a devastating surprise attack on U.S. forces, including cyber warfare and space attacks, resulting in the Chinese occupation of Hawaii as a forward base. Written by P.W. Singer and August Cole, Ghost Fleet is notable for its detailed research and realism; it includes concepts like drone submarines, AI, and next-gen weapons backed by extensive endnotes. Unlike the Hollywood films above, this book doesn’t parody the scenario – it treats it as a serious cautionary tale of what a U.S.-China conflict could look like. Its popularity in defence circles, even the U.S. Navy made it recommended reading, shows that the line between fiction and foresight can be thin.

The entertainment industry both mirrors and moulds public anxiety about foreign threats. In periods of high tension, filmmakers might channel fears into dramatic scenarios (Red Dawn), whereas with hindsight they might lampoon the overreactions of an earlier generation (The Russians Are Coming; 1941). The recurring motif is a foreign adversary suddenly appearing on American soil or just off its coast, be it a Soviet sub on a sandbar, a Japanese sub in Santa Monica Bay, or paratroopers in Colorado. Such images crystallise the abstract threat into a visceral scenario people can imagine, or laugh at.

Looking at today’s concerns, we have yet to see a blockbuster movie about a Chinese drone submarine popping up in San Francisco Bay, but it’s not far-fetched to imagine one in the future. So far, China-focused invasion scenarios have mostly been explored in novels and war-game think pieces, as with Ghost Fleet, rather than tongue-in-cheek comedies. This perhaps reflects the still-evolving nature of the China-U.S. rivalry and sensitivities around it. Interestingly, when Hollywood revisited Red Dawn in a 2012 remake, the invaders were changed from Chinese to North Koreans in post-production, reportedly to avoid offending Chinese audiences and investors, highlighting the complexities of modern geopolitical storytelling.

Balancing Real Threats and Perceptions

China’s new XXL undersea drones present a genuine strategic challenge: they could allow Beijing to project force across the Pacific in novel ways, undermining long-held assumptions of West Coast safety. The technical facts – 10,000+ mile range, autonomous operation, and potential swarming in numbers, warrant serious attention by U.S. defence planners. However, it’s equally important for the public and policymakers to keep these developments in perspective. History shows that while adversaries’ new weapons can inspire alarmist headlines and worst-case imaginings, those fears can also be tempered by knowledge and even humour.

Every era’s terrifying new weapon, be it the submarine, the missile, or the drone, eventually becomes better understood. Americans in the 1940s and 1960s were genuinely afraid of enemy subs lurking just offshore, a fear that later gave rise to satire once the immediacy faded. Today, as news emerges of Chinese spy balloons or robotic subs that might one day loiter off California, we should strive for a measured response: vigilant and prepared, but resistant to panic. The goal is to address the real capabilities of systems like the XXLUUV without inflating them into doomsday threats or, conversely, dismissing them as science fiction.

In the end, the interplay of technology and perception is dynamic. China’s extra-large underwater drones could indeed alter the balance of naval power in the Pacific, much as the introduction of nuclear submarines or long-range missiles did in earlier decades. How the U.S. responds, not just militarily but psychologically, will be telling. Will these drones become the subject of Hollywood’s next war thriller or satirical comedy? Possibly both. What’s certain is that understanding the reality of the threat is the best antidote to unreasoning fear. As we watch this new development beneath the waves, it’s wise to keep periscope depth on the facts and a healthy sonar ping on our collective imagination.

Read More:

- Asian Times: PLAN’s big underwater drones push undersea power toward US shores

- Naval News: China’s New Underwater Drones Could Threaten West Coast U.S.

- H.I. Sutton: Chinese Navy (PLAN) Extra-Large & Extra-Extra-Large Underwater Vehicles

- Wikipedia: Spielberg’s 1941

- I Draw on my wall: 1941 (1979)

- NDR: Bunker Books: Ghost Fleet – A Novel of the Next World War (2015)

- Time: Why 1984’s Red Dawn Still Matters

- The Saturday Evening Post: Red Dawn Revamped Ratings with Russian Fears

- Public Books: Deep Focus: “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming

- Factual America: 9 Documentaries on the Rise of Communism in the 20th Century

- YouTube: The World’s largest UUV !!! China New Super Sized XXL Uncrewed Submarines better than The US Orca

- JSTOR: The Tools of Owatatsumi: Japan’s Ocean Surveillance and Coastal Defence Capabilities

- Global Taiwan Institute: China’s Undersea Cable Sabotage and Taiwan’s Digital Vulnerabilities

- Small Wars Journal Irregular: Warfare on the Sea Floor and the Case for National Resilience