Frank Pierson’s The Looking Glass War is a slow-burning adaptation of John le Carré’s 1965 novel, and like much of le Carré’s world, it deals not in glamour or gadgets but in the decaying realism of the intelligence game. Unlike the bombastic Bond films of the era, this one is sober, chilly, and resolutely unglamorous.

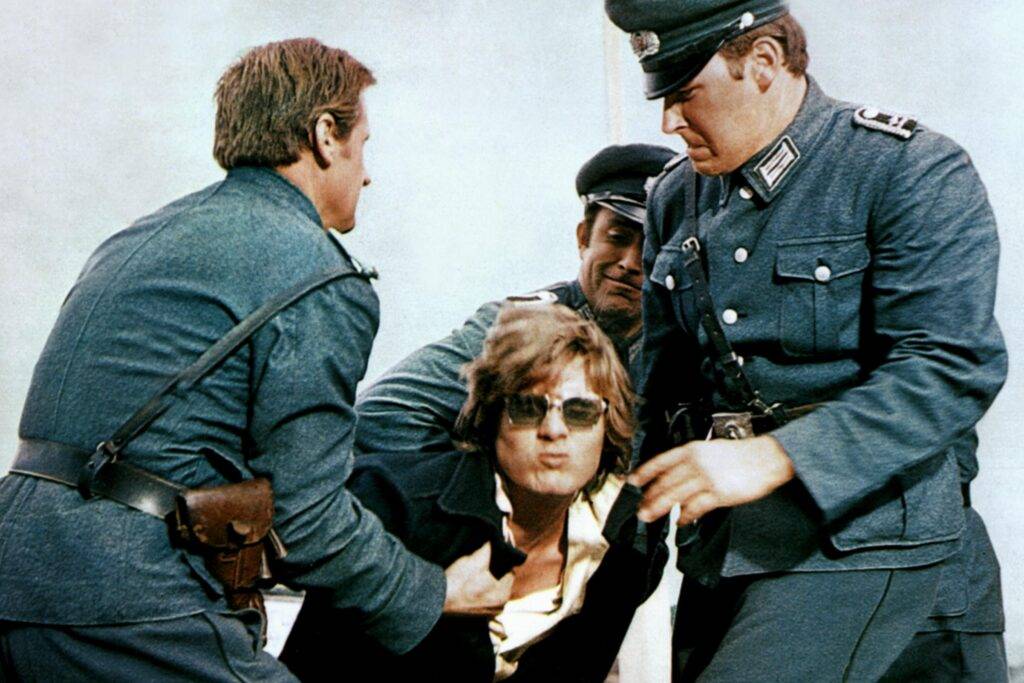

Starring Christopher Jones as Leiser, a Polish defector reluctantly recruited by the British intelligence service, a thinly veiled MI6, the film drops the audience into the back halls of Whitehall bureaucracy and into a grim Eastern European landscape riddled with paranoia and grey ethics.

The performances are muted but effective. Ralph Richardson, as the weary, calculating head of the department, brings weight and internalised cynicism to his role. Anthony Hopkins, in one of his early performances, plays Avery, a junior officer torn between loyalty and conscience. Jones, though handsome and physically fitting for the role, sometimes comes across as too detached, more model than man. Susan George’s brief appearances lend emotional weight to the otherwise male-dominated atmosphere.

Cinematography by Austin Dempster is suitably bleak. Washed-out hues, stark lighting, and lingering shots of lonely border roads reinforce the film’s grim message: espionage is less about action and more about expendability.

The pacing is slow by modern standards, but it fits the film’s thesis — that the world of spying is methodical, bureaucratic, and rife with betrayal.

A melancholic and slow-cooked thriller that rewards patience and historical interest more than visceral excitement.

Cynical Realism Wrapped in Bureaucratic Decay

The Looking Glass War is more than a Cold War period piece — it’s an autopsy of Western intelligence delusions in the postwar years. The story is rooted in a time when Britain still fancied itself a global player, but the machinery of its espionage world had rusted.

This film captures the essence of strategic miscalculation. The intelligence service, desperate for relevance and prestige, launches a half-baked infiltration operation to confirm Soviet missile activity. Their chosen agent is undertrained, poorly supported, and ultimately abandoned — a symbolic reflection of how civilians or immigrants were often used as pawns in Cold War proxy games. The operations are filled with mistakes: intelligence failures, poor risk assessment, and political interference. The planning is shoddy, the backup non-existent. For any defence analyst, this is a goldmine of cautionary insight:

- Recruitment Policy Flaws: Leiser is selected more for convenience than competence, echoing real-world cases where assets were poorly vetted.

- Command and Control: Field officers are disconnected from command priorities. Mission clarity is minimal, with unclear lines of authority.

- Moral Hazard: The film bluntly shows how human life becomes expendable when intelligence goals are driven by political ego rather than national security.

Le Carré himself had served in British intelligence, and the screenplay retains his core argument: the spy business, especially in fading empires, becomes a theatre of self-deception. The Looking Glass War is not a celebration of Western heroism — it’s a lamentation of imperial decline and strategic confusion.

A brutal, if understated, indictment of Cold War intelligence practices, with enduring lessons in operational ethics, risk mismanagement, and bureaucratic folly.

While The Looking Glass War may not thrill fans of fast-paced spy action, it is a vital entry in the genre for those interested in the grim, grey truths of the intelligence community. It lacks the sheen of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, but it delivers raw, tragic realism in its own claustrophobic way.